Ancient Egyptian treasures discovered in suburban Sydney home

The collection of 182 artefacts includes ceramic jars, a coffin fragment and amulets.

It's a dilemma familiar to anyone who has ever sold a family home: what to do with those forgotten treasures uncovered while packing boxes?

Rosemary Beattie faced that challenge on a grand scale when selling her mother's place in Northbridge. Margaret "Molly" St Vincent Welch had lived in the house for 59 years, but at 91, her health was failing and she needed to move into care (she has since passed away). Her home was full of objects accumulated over generations, including a wooden display case packed with almost 200 artefacts from ancient Egypt.

"It had been sitting on a closed‑in verandah on top of a cupboard," says Mrs Beattie. "We brought it down and thought, 'What are we going to do with this?'"

I had been told there was a mummified cat in the case.

The collection of coffin fragments, stone figures, amulets and a mummified animal had come to Mrs St Vincent Welch through her late husband, Dr John Basil St Vincent Welch, who had inherited it from his father – also John Basil St Vincent Welch – a First World War doctor whose service included time in Egypt.

Lieutenant Colonel St Vincent Welch DSO died of influenza shortly after returning from the war. The artefacts he had purchased in Egypt as souvenirs remained in his wife's Cremorne home for decades, before moving with his son to Northbridge.

Mrs Beattie remembers the case from childhood visits to her grandmother. "I had been told there was a [mummified] cat in there," she remembers, "which at five or six, I thought was fascinating."

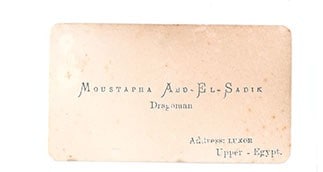

During his time in Egypt, Lieutenant Colonel St Vincent Welch employed a local guide to connect him with a then-thriving antiquities market. The guide's business card was still in the case when Mrs Beattie and her husband found it at her mother's house almost a century later.

Her grandfather had studied medicine at Sydney, so the family decided to donate the collection to the University's Nicholson Museum. After considering the acquisition carefully, according to the responsibilities set out by UNESCO regarding the transference of antiquities, the curators arrived at the house to pack all 182 objects.

The collection has now been catalogued and will go on display when the University's new Chau Chak Wing Museum opens. It will feature in an exhibition about private collectors, including several other Australian servicemen who brought objects home from Egypt.

For Mrs Beattie, the experience has provided new insight into her family's history. "My father was so young when his father died, so we never really knew much about him," she says. "This has been a real journey of discovery."

Inside the collection

Mummified cat

Or is it? It's wrapped to look as though it has feline ears, but there is something odd about its shape. It may be a fake – albeit an ancient one. Mummies created to resemble animals were often bought by poorer Egyptians as budget offerings to the gods.

Record number: NM2017.262S

Scarab

On the underside of this glazed scarab with a nail through its centre is the Egyptian hieroglyph for "good" or "perfection".

Record number: NM2017.228

String of beads

The amulet necklace is made of stone and faience - a material that hardens into bright colours when fired like clay.

Record number: NM2017.232

Coffin fragment

This painted fragment – once part of a coffin or mummy covering – is made of layers of linen and paste.

Record number: NM2017.263

Ceramic jar

The broken jar has been reconstructed with medical tape. Once upon a time it might have been used to store an animal mummy.

Record number: NM2017.258

Guide's business card

The name on the yellowing card is Mustapha Abd-El-Sadik, a dragoman who offered his services to foreign soldiers in Egypt during the First World War. He would have arranged visits to sites and helped purchase antiquities as souvenirs.