ATARs to blame for fall in language study

“Students give low ATARs as the main reason for dropping out of languages even though they report liking their language study,” Director of the Sydney Institute for Community Languages Education at the University of Sydney, Dr Ken Cruickshank said.

In the 1960s, over 40 percent of final year students in Australia studied languages; that figure has fallen dramatically and now only 8 percent of Year 12 students in NSW study a language. Now, Australia ranks as the lowest of all OECD countries in the study of languages.

Governments have introduced more than 70 programs, reports and reviews in Australia over the past 40 years to halt the decline without any effect. But they all fail to address what the researchers identified as the root cause of the problem, different scaling marks for different languages.

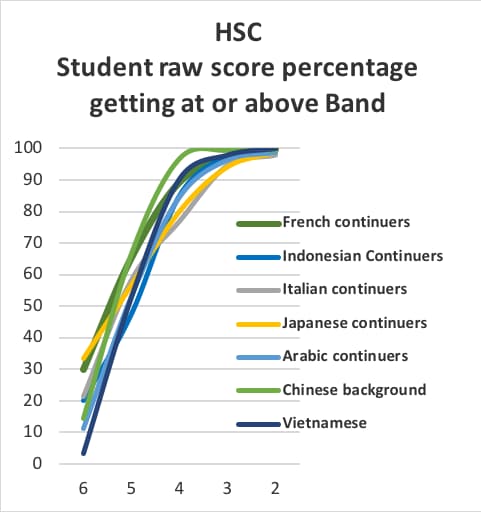

HSC exams are set by national and state education authorities to be of equal challenge and difficulty, resulting in similar raw HSC marks for different languages.

Source: UAC, 2016 Scaling Report for the NSW HSC

However when languages are scaled, a difference in how students score between languages becomes clear. Each language is scaled according to factors such as how each student cohort compares with how they score in other subjects and how they compare with the overall candidature.

The result of this process means those in less wealthy government and Catholic schools do not do as well. Research shows that students in lower socio economic status (SES) schools do not perform as well in English and maths subjects, which impacts how their language marks are scaled.

Source: UAC, 2016 Scaling Report for the NSW HSC

Languages such as French, that are taught in private and government selective schools, achieve higher ATARs compared to community languages like Arabic, Chinese background and Vietnamese. Community languages are scaled 50 per cent lower than French, with most students getting ATARs under 25 out of 50.

Before the 2000 recommendations from the McGaw Report into reforming the Higher School Certificate, all languages were scaled the same as French. After that time, each language was scaled separately because it was felt that students in community languages and in lower-SES schools were getting an ‘unfair’ advantage.

Community languages which are mainly taught in low-SES schools, traditionally gave students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds an opportunity to develop their home language and access tertiary study.

“More than 80 per cent of students taking community languages were in lower-SES secondary schools. The ATAR creates a hierarchy of languages and replicates SES differences rather than differences in language proficiency,” Dr Cruickshank said.

The study, led by the University of Sydney in collaboration with the University of Wollongong and UTS, found that nearly all of the 140 students interviewed reported not choosing languages for the HSC if they thought they would get below Bands 5 or 6.

“Regional and rural schools and low-SES city schools are not offering elective languages in year 12. The reason is simple – if you do not get Bands 5 or 6, you get a low ATAR and you are better off choosing other subjects,” said Dr Cruickshank.

Only 20 percent of schools from lower-SES areas offer languages in year 12 compared with 65 percent of schools from higher-SES areas. Private schools account for 35 percent of year 12 languages enrolments and only 3.1 per cent of Catholic school students in Sydney study a language for the HSC.

Languages have shrunk back to the 1960s where prestige languages such as French, Latin and German were studied in elite private and government schools. Since 2007 French, German and Latin have grown in enrolments by between 15 and 28 percent but Chinese and Japanese, studied in other schools, have declined by the same amount.

“We need to go back to scaling all languages the same as French or getting rid of ATAR for languages. We are punishing students who have learned their language in the community and those who attend less wealthy schools. Scaling does nothing to credit language proficiency. We know that learning a language benefits the development of thinking and cultural understanding – why are we not giving young people the chance to study languages?” said Dr Cruickshank.