Strange case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde filled with dark imaginings

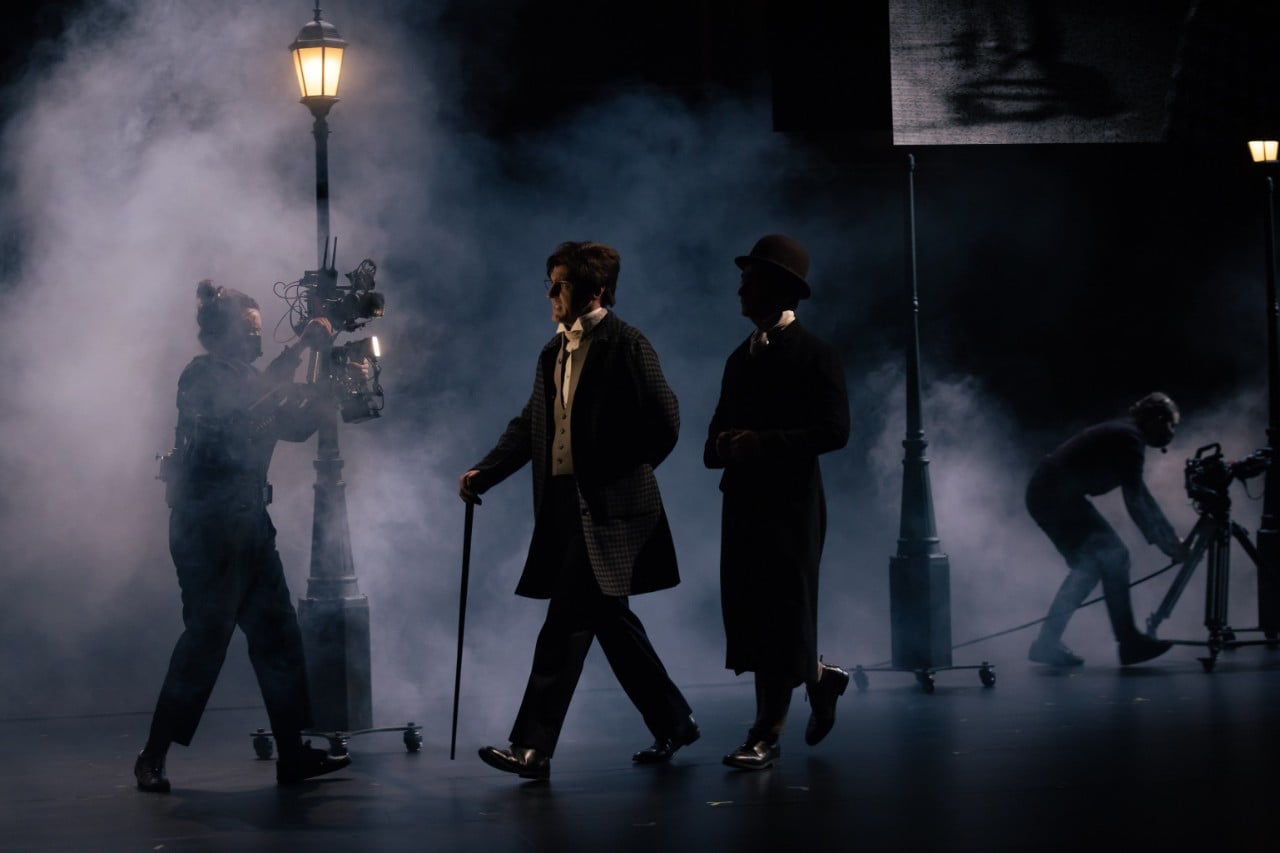

Ewen Leslie and Matthew Backer in Sydney Theatre Company’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, 2022. Photo: Daniel Boud

With their new production, Kip Williams and the Sydney Theatre Company have revisited the artistic and box office success of 2020’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. As with that show, the narrative of Jekyll and Hyde is driven forward by a dazzling mix of live performance, filmed action and recorded video. The intensity this combination brings to the storytelling is, if anything, dialled up in the new production, which hurtles towards its climactic moments with compelling force.

However, where Dorian was bathed in the gorgeously exotic colours of Wilde’s novel, the aesthetic of the new production is an austere black and white, with flashes of colour bursting out only at crucial revelatory moments. Otherwise, the look is Noirish, borrowing a visual language for Victorian London from movies such as Basil Rathbone’s 1940s Holmes films.

Gaslight, fog and mysterious doorways invite us simultaneously into the story and into the splintered psyche of its protagonists.

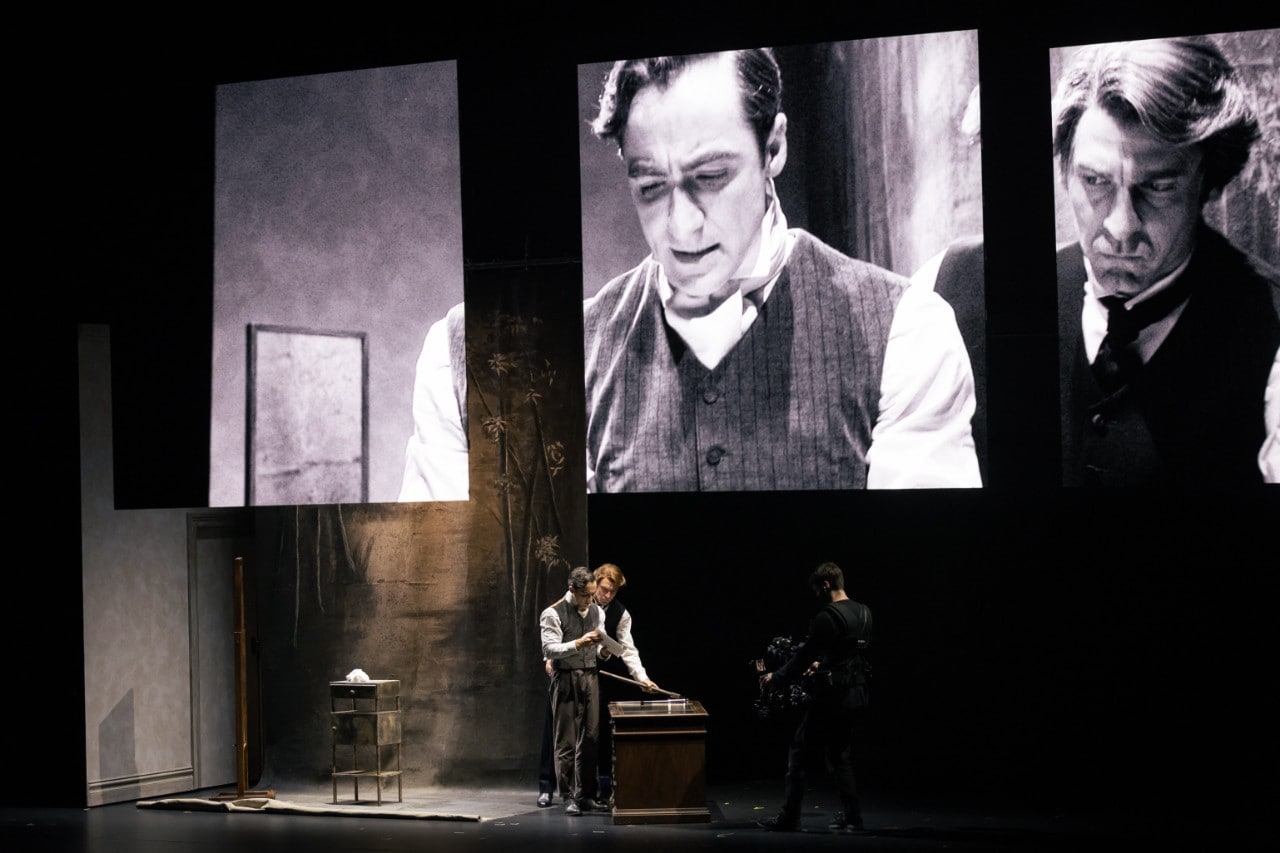

A bold choice for this production is to use almost all of Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella as the basis for the dialogue. The two performers narrate their action as well as performing the dialogue. They address us mostly through the camera, building an intimate picture of disintegrating personalities.

Transformations of body and voice

Ewen Leslie, as both Jekyll and Hyde (as well as most other characters), gives us the virtuoso performance we have come to expect from him. Leslie’s capacity seemingly to transform his body and voice in the blink of an eye lends itself brilliantly to the story.

The revelation for me, however, was Matthew Backer. Unlike Leslie, Backer takes on just one character: Mr Utterson, the lawyer. In Stevenson’s words, this austere “man of a rugged countenance”, “never lighted by a smile” is the person through whom we initially experience the events of the story.

Matthew Backer and Ewen Leslie in Sydney Theatre Company’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, 2022. Photo: Daniel Boud

Backer captures Utterson’s button-downed anxiety at what he witnesses. He seems, on the face of it, to be a censorious observer, all Victorian repression and severe commentary. However, the production’s shrewd use of Stevenson’s words, and Backer’s own subtle performance, ensures that Utterson’s own implication in London’s twilight world of pleasure and violence is foregrounded.

Double Lives

It is telling that Dorian Gray and Jekyll and Hyde were written and published within years of each other. Stevenson’s brilliantly written short novella came out in 1886, with Wilde’s novel following in 1890. Darwin’s theories of evolution had already been in circulation for a couple of decades, and Sigmund Freud’s first book emerged in 1891. Both novels make their own literary contribution to this late nineteenth-century exploration of the limits of the human.

However, both of these stories of men leading double lives might have had something more urgent in their sights. Utterson’s initial suspicions, when confronted by his friend Dr Jekyll’s strange behaviour and Jekyll’s seeming tolerance of the vicious Mr Hyde, is that he is being blackmailed.

In 1885, the year before Jekyll and Hyde made their first appearance in print, a law was passed that specifically criminalised all homosexual activity between men. Known as the Labouchère amendment, it also came to be known as the “blackmailer’s charter”. It was a licence to threaten men with exposure, and it is the law under which Wilde was eventually prosecuted and sentenced just a few years later.

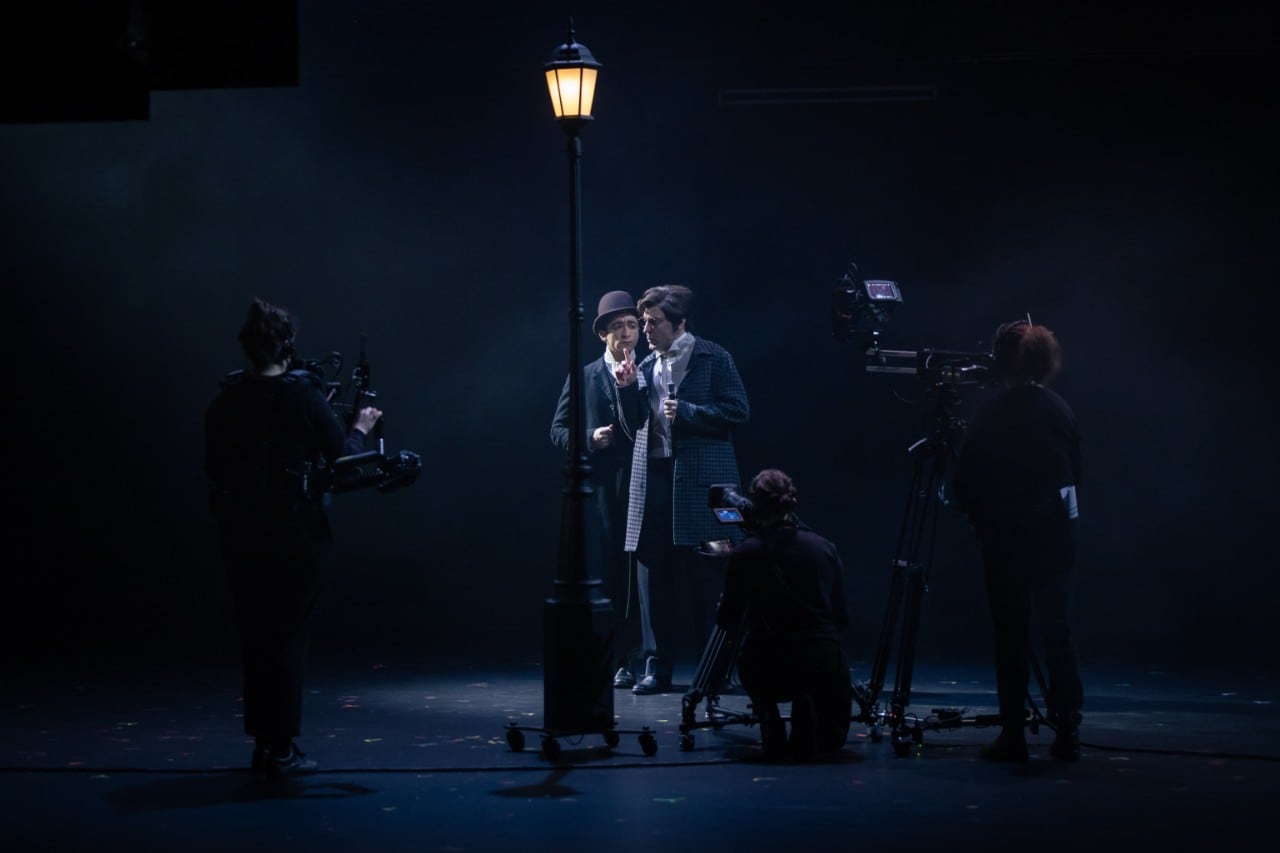

Ewen Leslie in Sydney Theatre Company’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, 2022. Photo: Daniel Boud

Set in the all-male world of middle-class, professional London, Stevenson’s novella skirts around the possible implications of male friendship, especially as combined with urban pleasures or the potential dangers of new scientific exploration. What emerges - and what is brought out brilliantly and subtly in this production - is not so much the traditional horror story of good versus evil.

Rather, this is a more complex portrayal of a society’s moral compass being painfully realigned in a new world of discovery. Utterson is as fascinated as he is repulsed by his glimpses of a world from which he only imagines himself to be separate.

In this context, Williams’ bravura use of video technology combined with live action (just wait for the exciting “staircase” scene!) is a particularly appropriate vehicle for investigating these complex influences on both the human psyche and the human body.

Matthew Backer and Ewen Leslie in Sydney Theatre Company’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, 2022. Photo: Daniel Boud

It is great that the STC has been able to put this set of artists together again. From Nick Schlieper’s lighting, through to Clemence Williams’ powerful score and the video design of David Bergman, this is a production to satisfy Sydney’s darkest imaginings on these chilly winter nights.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, directed by Kip Williams, is on at the Roslyn Packer Theatre until September 3. Hero image by Daniel Boud.

This theatre review was first published in The Conversation as A production to satisfy Sydney’s darkest imaginings: Sydney Theatre Company’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Associate Professor Huw Griffiths is an expert on sixteenth and seventeenth-century English literature and culture, with a focus on Shakespearean drama.