Engineering technology to help prevent concussion in sport

A biomedical engineering team from the University of Sydney's Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology is developing new technologies to aid medical research into concussion in sport.

Biomedical engineering Dr Philip Boughton from the Faculty of Engineering is currently working with researchers from Sydney Medical School to develop a suite of technologies to better detect and assess traumatic brain injuries.

Dr Boughton and a team of PhD and Masters students are developing wearable biosensors to monitor impacts.

"We're trying to build technology that can track and relay real-time data on the acceleration, deceleration and rotation of players' heads and necks. We want these biosensors to indicate not only concussive single impacts but also tell us when several smaller impacts could add up to a concussion," he said.

"At the moment we are in the prototype stage, however the plan is to implant this technology into a mouthguard. The hope is when a force that is likely to result in a concussion or brain injury is detected, the mouthguard will change colour or vibrate, alerting the player, training staff and referee to the injury.

"We hope that by developing a mouthguard it will be something that will become available to players at all levels of sport – from amateur through to fully professional athletes."

The team's work forms a vital part of multi-disciplinary research into the causes, assessments and treatment of concussion in sport.

Led by neuro-ophthalmologist Associate Professor Clare Fraser of the University of Sydney's Save Sight Institute and Dr Adrian Cohen, an adjunct senior lecturer at Sydney Medical School and founder of Headsafe, the research aims to prevent health effects that result in long-term harm and even death.

With no accepted, singular diagnostic tool for concussion, the team is working with Randwick Rugby Union Club to validate concussion tests that will aid the development of a more accurate system to diagnose mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI).

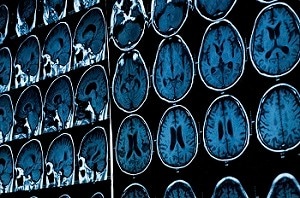

The researchers have worked with the club for the past three years, collecting data from a range of tests including XPatch accelerometers attached to players, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), cognitive tests, balance tests, salivary biomarkers and MRIs. So far this data has allowed researchers to compile baseline metrics that is improving the detection and diagnosis of concussion in players tested during and after games.

Dr Cohen said the aim of the research was to develop a set of objective tests and measurements to assist in the diagnosis and treatment of concussion.

"Concussion reflects the amount of energy the brain absorbs from an impact and can be very difficult to diagnose", he said.

"Less than 10 percent of people who suffer a concussion are knocked out and many symptoms are not apparent to those watching. We need to take the subjectivity out of it."

Associate Professor Fraser is researching how the processing of information from the eyes can be used to diagnose concussion. She said the main issue when addressing concussion was its broad definition and underestimated danger to player health.

"Our main concerns regarding mTBI surround the lack of strong diagnostic criteria and that there are a lack of objective markers for diagnosis. Players risk serious health complications if they return to play too soon", she said.

"They risk ongoing brain injury if they receive a second impact before recovering from the first. Players also risk long term degenerative brain diseases including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), dementia, personality/mood changes and psychological disturbance including depression."

The goal for the researchers is to develop a test that can accurately and objectively diagnose concussion and be used by non-medical professionals at all levels of sport with a view to preventing long-lasting damage, especially to developing brains in children and adolescents. It is believed that visual testing may prove to be the most reliable, portable and easiest to implement test in schools and amateur sports.

"Unfortunately, only professional sports teams have doctors on the sidelines", said Associate Professor Fraser.

"We hope our research will improve the way concussion is diagnosed across all grades of sport and will make it safer for all players. In particular, we hope these tests can be used by sports trainers, coaches and teachers to guide them on when to remove a player from the field and send them for assessment and possible treatment."

Dr Cohen said the research team wasn't trying to "soften" sport but make it safer for athletes and educate sports teams and the community about head injuries.

"Sport has so many positive benefits but we need to ensure players are aware of the risks they are taking. We also need to increase our understanding to give participants and their families confidence that we are looking after them throughout their careers and after they stop playing."

Dr Cohen is also the founder of not-for-profit charity Headsafe, and is extending a global Rugby Player Health Research Project to Australia. An online questionnaire covers general and psychological health, whilst specialised visual, TMS, MRI and biomarker tests on retired Australian rugby, rugby league, AFL, equestrian and non-contact athletes will add to this important international collaboration with centres from the UK, New Zealand and Canada. Players can enroll here.

Related articles

Sydney performs strongly in engineering and computer science rankings