How giving has created history

Bequests have the power to fast-track the vital work we do at the university. The generosity of those who believe in the betterment of society through education has become an integral part of the University's history. It's been that way since 1850.

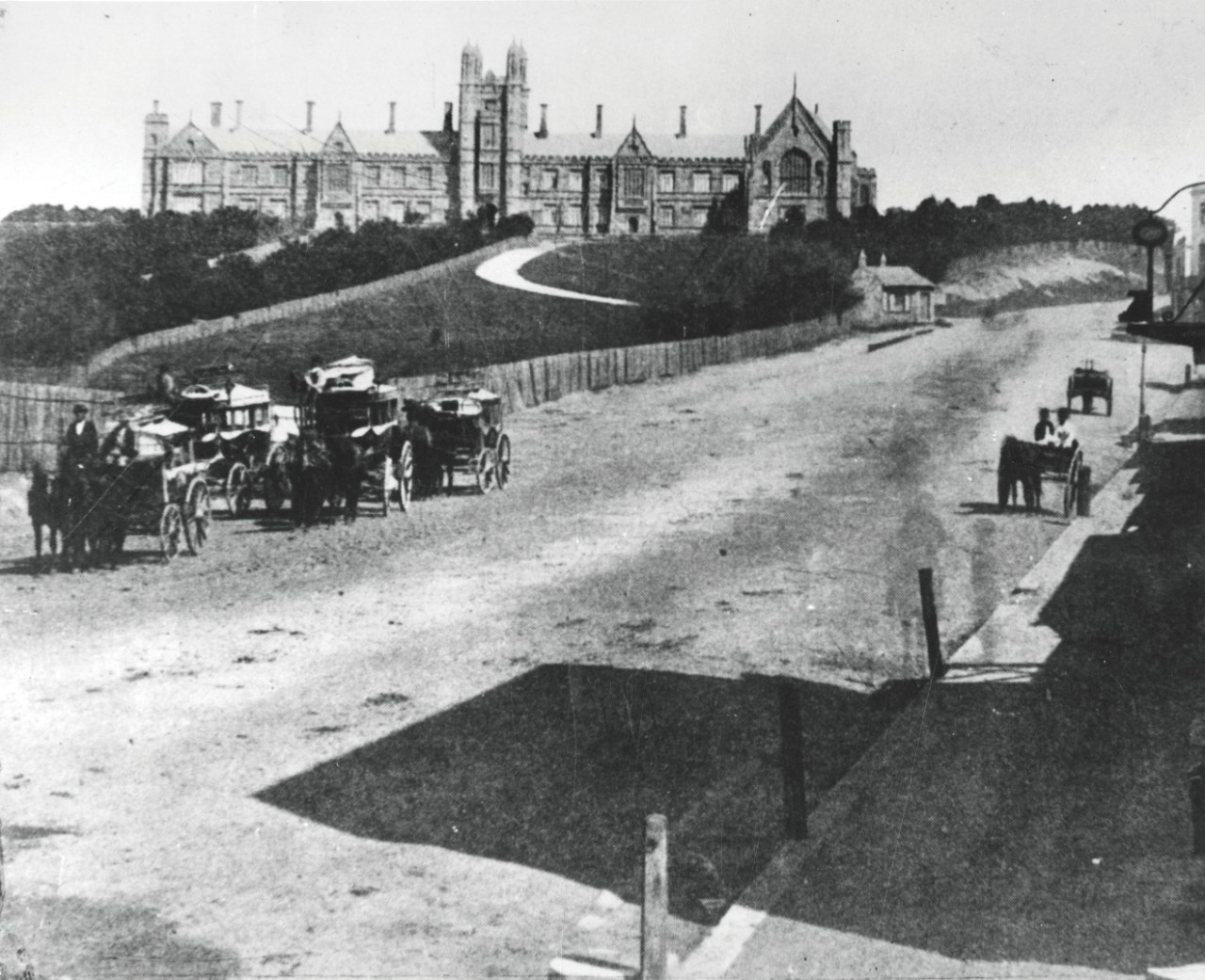

View from Parramatta Road to the Quadrangle, 1870.

Since 1850 the University has relied on the generosity of many to sustain it. Benefaction has come from individuals who subscribed to the belief in the betterment of the world through education and scholarship. This has been vital to the history of the University,” says Associate Professor Julia Horne, Historian and Co‑author of Sydney: The Making of a Public University.

In 1853, only a few months after the admission of the first student, a benefactor drew up an endowment agreement with the University. Thomas Barker’s gift of £1000 held great symbolic significance; the interest alone was enough to fund a student scholarship.

In 1880, a bequest from the society’s namesake, John Henry Challis, of £276,000 (valued at more than $45 million today), set a precedent for inspired giving. Used to set up the University’s first professorships in the areas of Law, Medicine, Veterinary Science, Biology, Civil Engineering, English Literature, History and Philosophy, the bequest changed lives and history at Sydney.

“The Challis bequest had a further influence in articulating the meaning of the University to late 19th century colonial society,” Associate Professor Horne says.

Fernand Léger’s Académie Moderne, Paris, c. 1924, silver gelatin photograph, 16.5 x 35.5 cm, photographer unknown; Edith Power Bequest 1961, the University of Sydney, managed by the Museum of Contemporary Art. J. W. Power is pictured 5th from left.

Since then, bequests of great significance have made a profound impact on the University’s work, from feline research to research into cancer, creating research chairs, funding science and engineering disciplines, and establishing the Macleay Museum to house Sir William Macleay’s natural history collection, as well as Fisher Library. During the Great Depression, when the NSW Government had reduced its funding to the University, bequests were particularly important. In 1919, the University was grateful to receive a bequest in the order of one-third of grazier Samuel McCaughey’s £1 million estate (his gift to the University is valued at more than $23 million today). McCaughey, who made his fortune from sheep and wool, left this endowment for general purposes.

Similarly, George Henry Bosch changed lives with donations he provided throughout the 1920s to support cancer research. In 1927, his donation of £27,000 endowed the Chair in Histology and Embryology and, in 1928, he gave the University a further £200,000 to create chairs in Medicine, Surgery and Bacteriology.

“These chairs were a great step towards strengthening the clinical teaching and research capacity of the Faculty of Medicine,” Associate Professor Horne says. “In addition, they made it possible for the University to apply for support from the Rockefeller Foundation for the construction of the new medical school.” When Bosch died in 1934, he left most of his estate to the University of Sydney Medical School.

Women have also held a significant place in the history of benefaction at the University. “As early as 1874, women approached the University to give money for scholarships and lectureships, sometimes as part of their husband’s dying wishes,” says Associate Professor Horne.

The first woman to make a bequest to the University was Sophia Hovell in 1876. The wife of William Hilton Hovell, explorer and settler, her legacy of £6000 in memory of her husband established a lectureship in Geology. Now known as the Edgeworth David Professor of Geology and William Hilton Hovell Lecturer, the bequest reflected the need to expand science as a new degree.

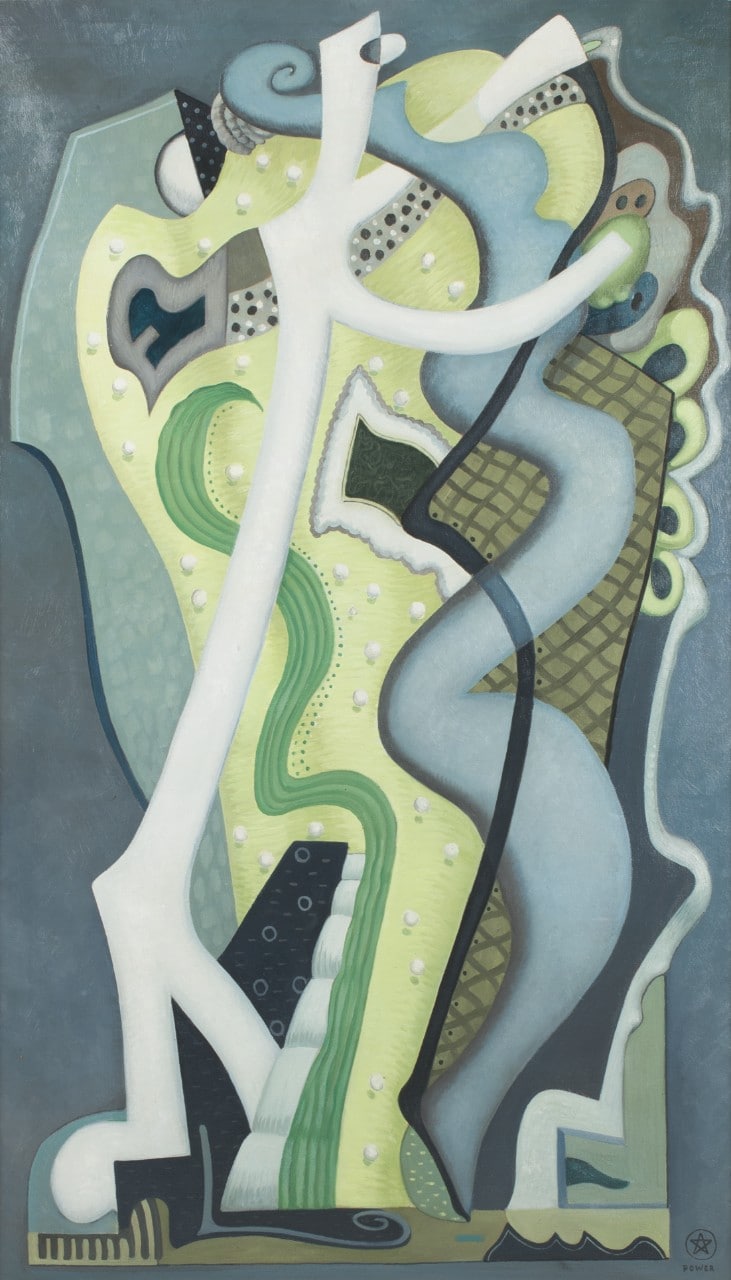

J. W. Power, Apollon et Daphné, 1929 oil on canvas 109.5 x 63.6 cm Edith Power Bequest 1961, the University of Sydney, managed by the Museum of Contemporary Art.

The arts, including fine arts, writing and music, have also benefited greatly from generous bequests. In 1961 John Wardell Power left £2 million (valued at more than $45 million today) to be used to introduce the latest artistic ideas from around the world to Australia.

“The Power bequest, which came into effect in 1962 after the death of his wife, Edith, enabled the University to purchase a diverse collection of contemporary art – from pop art to Latin American kinetic art,” says Associate Professor Horne. “It also established the Power Institute with a research library, public education program and a residency scheme for Australian artists at the Cité Internationale des Arts cultural complex in Paris.”

The Power Bequest also provided core funding for Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, opened in 1991. Also in 1962, Eleanor Wood left £415,000 (now worth more than $11 million) to establish travelling scholarships and Sydney University Press, while in 2005 George and Mary Henderson bequeathed $16 million for the advancement of music.

“One of the largest collections of ancient artefacts in the country and notable ethnographic, natural history and art collections belong to the University,” Associate Professor Horne says. “The University is responsible for the care and upkeep of these valuable collections, all of which come at significant cost, rarely covered by government funding.

“In addition to supporting the brightest and most deserving students, philanthropy has contributed to developing a general liberal education, especially the support and development of the arts and sciences,” she says.

Bequests have changed lives and the course of history at the University and continue to do so today.

Your bequest can change the future

To talk about what’s possible, contact our bequest team on +61 2 8627 8492, or via the website at: sydney.edu.au/bequest