What’s that weed in my rice field?

A new smartphone application developed by a University of Sydney Masters student will help the plight of Cambodian farmers to manage the spread of weeds in their rice fields.

A student from Meanchey University demonstrating the use of the WeedID App to a Cambodian rice farmer.

Weeds can have a huge impact on the quality and quantity of rice produced, and in turn this can have devastating financial implications for smallholder farmer livelihoods and food security.

Failure to manage weeds at critical periods can result in yield losses of more than 50% and it is not just the presence of weed plants during cultivation that is a problem; weed seeds can contaminate the rice grain at harvest resulting in a lower rice selling price or even worse, product rejection at rice mills with consequent negative financial impact on farmers.

A new mobile phone app is helping Cambodian rice farmers manage the spread of weeds at various stages of rice production, and will ultimately improve yields, increase financial gains and build knowledge of crop management in farming communities.

WeedID for iOS and WeedID for android, developed by Master of Agriculture and Environment student, Yehezkiel Henson and a small team of researchers, has been patented, and is already in use in Cambodia.

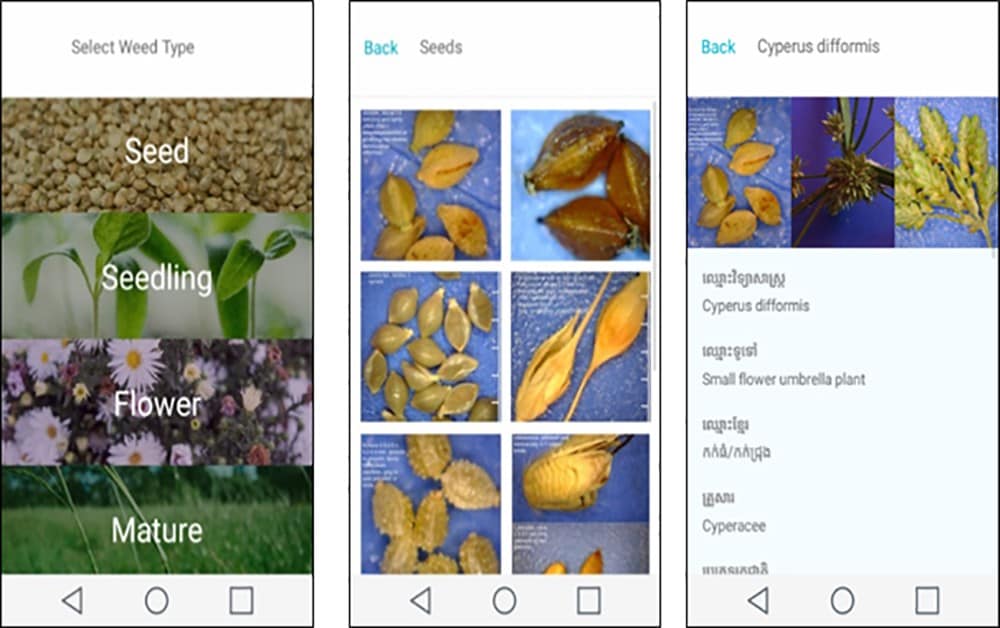

“WeedID contains a photo dictionary of the most common weeds in northwest Cambodian rice fields at different stages of growth. The app has images of seeds, seedlings, mature plants and flowers that will all help to identify the weeds which are devastating Cambodian farmers’ rice crops,” said developer and student, Yehezkiel Henson.

The WeedID app contains links to specific management information and details the most appropriate way to manage the weed.

In an initial appraisal of the problem, a weed seed contamination survey was conducted in the Cambodian provinces of Battambang and Takeo, and seeds of 41 different weed species from 13 plant families were found in rice samples.

“The patented app currently has a database of 45 weeds which covers more than 95% of the most common weeds in Cambodian rice fields.”

The idea is that farmers will be able to observe a weed in their field, identify it using the photo dictionary and then apply the appropriate management method.

“Different weeds require different management techniques. Depending on the life cycle, nutrient requirements or mode of reproduction, we will employ a different method of management.

“Some weeds, such as awnless barnyard grass (Echinochloa colona) can be managed simply by flooding the fields to drown them. Sometimes we may need to apply specific selective herbicides to manage them, as in the case of the smallflower umbrella plant (Cyperus difformis), also known as ‘dirty Dora’ in Australia.

“The WeedID app contains links to specific management information and details the most appropriate way to manage the weed,” said Yehezkiel.

Screen shots of the WeedID App showing the homepage (left), a photo gallery of weed seeds (middle) and an information page of a specific weed species in Khmer language (right).

Associate Professor Daniel Tan from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences and the Sydney Institute of Agriculture commissioned the app as part of an Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) project that is examining sustainable intensification and diversification in the lowland rice system in northwest Cambodia.

Yehezkiel developed the interface with start-up funding from the International Environmental Weeds Foundation (IEWF) and the Crawford Fund using data from Dr Robert Martin’s Cambodian weed database. A mobile app prototype was built by Nicholas Barker under the supervision of Associate Professor Rosanne Quinnell who were both involved in the development of the CampusFlora App.

Daniel Tan said the motivation behind the development of the app stemmed from the statistics surrounding mobile phone use in Cambodia.

“Figures from the World Bank suggest there are 133 mobile phones for every 100 people in Cambodia, which is on par with Australia, and more than the United States of America, which has 118 phones per 100 people.

“And smartphone ownership in Cambodia is growing more than 40% each year.

“The use of mobile phones is obvious to us when in the field and conducting research in Cambodia. Many people have a couple of phones and they frequently access the internet and social media,” Daniel said.

“The Cambodian smallholder farmers we work with are also hungry for information and use the technology available to solve problems. Farmers have shown us photos of pest animals, weeds and diseased plants taken on their phones, which our team have been able to identify. This prompted the idea to develop a free, user-friendly mobile tool to identify weeds in rice paddies so farmers can manage the problem and improve the crops that support their families.

“There are useful identification guides online and in paper form, but this app goes one step further to improve the accessibility of identification and management tools. We have also translated the app into Khmer which will improve access to the information and management solutions,” Daniel said.

So far, 41 Cambodian farming families have tested and provided feedback on the app and it is proving to be an apt tool to transfer information regarding weed identification and management to empower Cambodian farmers to make better farming decisions and practices.

“We have started with weeds as they are the most common issue identified by the rice farmers we have been working with in the ACIAR project. The next steps might include expanding the app to incorporate a picture dictionary of animal pests or common pathogen symptoms,” said Yehezkiel Henson.

“My masters project has enabled me to work on a practical, real-world solution for farming communities in Cambodia, and I’m really looking forward to investigating the benefits of this contribution and I hope it improves the situation for the families involved.”