Dressing up for Melbourne Cup Day: a racehorse point of view

What is a horse allowed to wear to the race that stops the nation?

Melbourne Cup is upon us and racegoers will dress in their finest, with prizes awarded for the smartest fashions on the field.

Just like the punters, the equine stars of the track may also be wearing a range of gear in the hope of gaining a winning edge.

Racing Australia’s list of approved gear covers more than 100 items that can be used in horse racing.

We’d like to help you identify what any racehorse you see may be wearing, and to distinguish between winkers and blinkers, nose rolls and nose bands, ear plugs and ear muffs.

So, let’s take a look at some of these items available in thoroughbred racing.

From blinkers to bandages

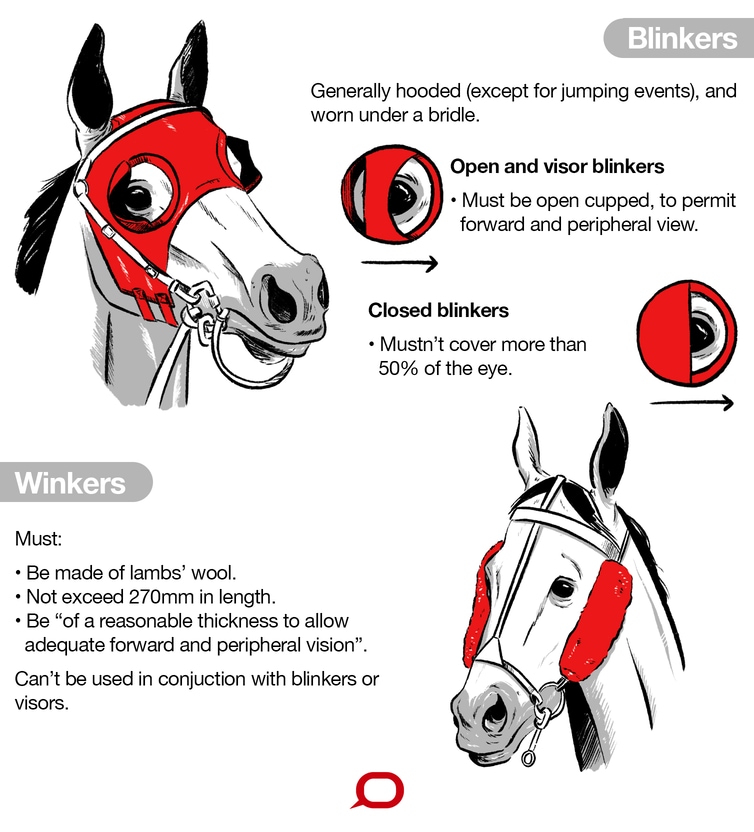

Blinkers, visors and winkers are cups or padding attached to the head to limit a horse’s vision in various ways. With their extraordinary wraparound vision, horses can normally see across 320 degrees without moving their heads.

The use of this type of equipment is thought to minimise distractions from other horses in the race, enabling the horse to focus on running rather than on other runners (or indeed the crowd).

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

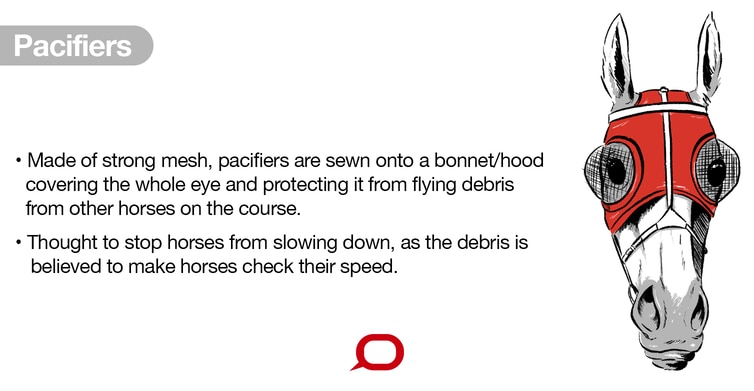

Pacifiers are mesh cups sewn onto a fabric bonnet to protect the eyes from debris kicked up by other runners, something that is believed to cause some horses to slow down.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

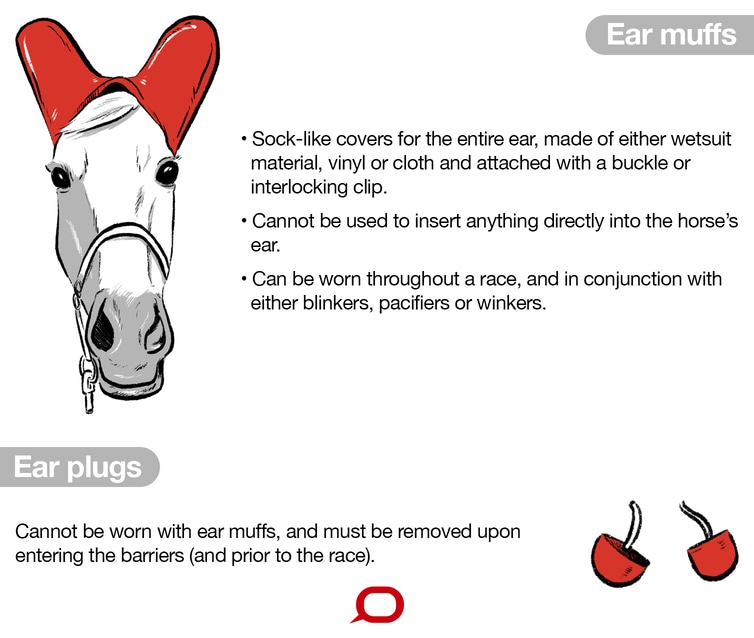

Ear muffs are sock-like and encase the whole ear. They are worn in the mounting yard and throughout the race, reducing the effect of the noise from race crowds which can frighten some horses. Ear muffs can be used in combination with blinkers, pacifiers and winkers.

Ear plugs, which are inserted into the ear, must be removed once the horse enters the barrier.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

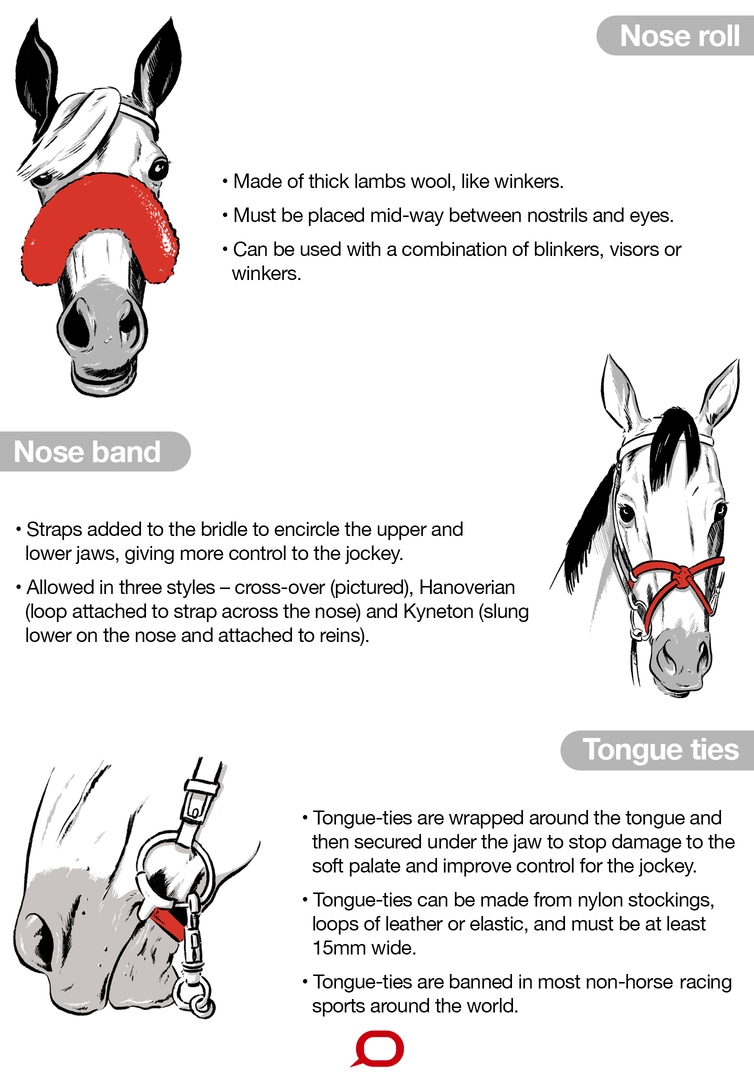

A nose roll is a thick sheepskin sausage that is used to stop horses being distracted by objects in their immediate foreground such as shadows.

Nose bands are straps added to the bridle and encircle the upper and lower jaws. They can be used to prevent horses from opening their mouths, giving the jockey greater control.

Tongue-ties involve looping a piece of elastic band, strap or nylon stocking around the tongue and securing it to the lower jaw. They are also thought to improve control as well as prevent displacement of the soft palate that can interfere with airflow to the lungs. A metal or rubber version called a tongue clip can also be used.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Germany has banned tongue-ties in racing and they are banned in most other horse sports around the globe.

RSPCA Australia is keen for tongue-ties to be banned in Australian racing due to concerns including the tightness with which they are applied.

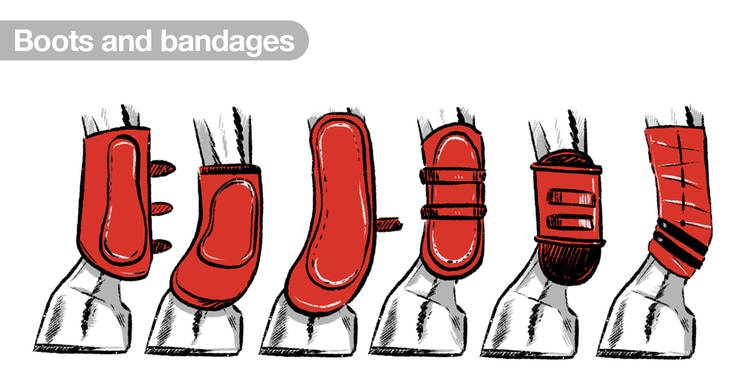

Boots and bandages are used to prevent injuries to the legs, notably self-inflicted injuries in horses that can accidentally strike one of their legs with another, and also to protect recent skin wounds.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The bit

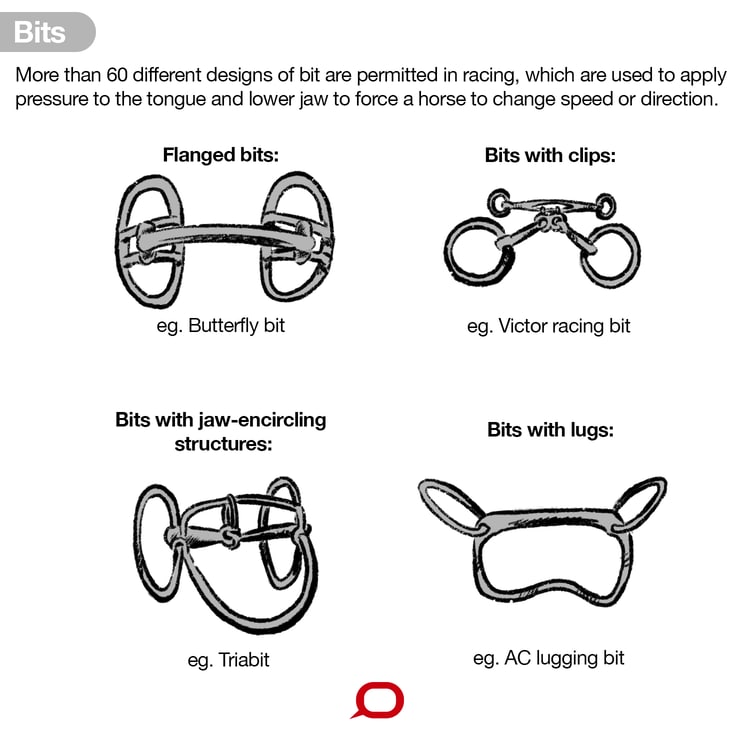

More than 60 different designs of bit are permitted in racing. The main purpose of a bit is to apply discomfort on the tongue and lower jaw of the horse to motivate it to change its speed or direction.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Many of the bits on the approved list are simple, ancient designs, whereas others are complex pieces of engineering with flanges, clips and jaw-encircling structures.

These are intended to address specific behavioural problems such as lugging (veering to one side) or over-galloping (galloping with a high head position while straining at the bit).

Relatively little is known about how bits function inside a horse’s mouth but radiographic studies back in the 1980s on live horses have shown that many bits do not work as believed.

The tail chain

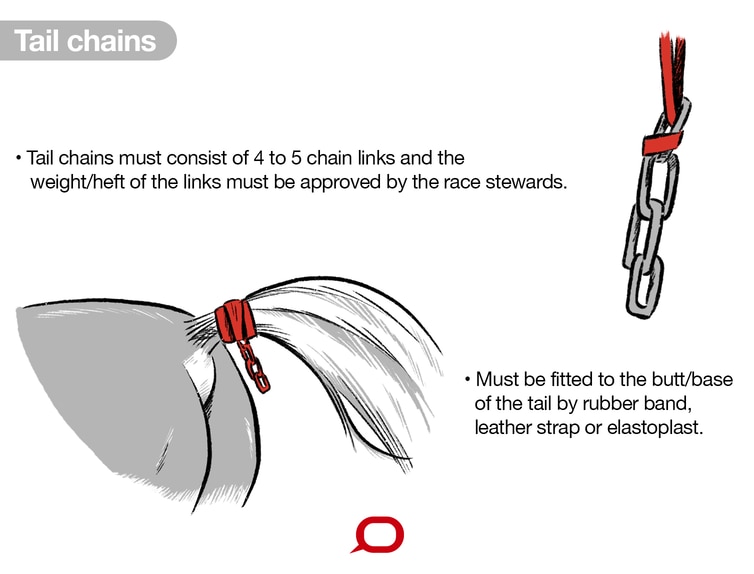

The tail chain is a short length of metal chain secured to the top of the tail by a rubber band and then hangs between a horse’s buttocks.

Anecdotally, it is believed to dissuade the horse from taking air into its rectum as it gallops, thereby preventing abdominal pain and associated poor performance.

However, given the anatomy of the horse’s gastro-intestinal tract, it seems unlikely that such air intake could affect performance in this way, or alternatively that a tail chain could reduce any such effect.

It is possible that the chain hitting the soft tissues of the perineal area may motivate the horse to gallop harder, which could be seen as performance-enhancing.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Does the gear make a difference?

A fascinating study of the behaviour and apparatus that horses wear when racing revealed associations with horse performance on the day. It showed poor performance was associated with boots, bandages, jaw-encircling nose bands, nose rolls, and pacifiers.

But this study was published in 1997 and since then there has been little published independent research on the use of any racing gear and its effect on racehorse performance.

The potential for gear to affect performance is fundamental to the integrity of racing. The rules of racing state that permission to use any piece of approved gear other than basic snaffle bits has to be given by the stewards before the horse starts the race.

Once permission has been given, the horse must continue to race in that gear unless the stewards grant permission for it to be changed. Form guides and starters lists detail gear changes to enable punters to assess the potential effect on the horse’s performance.

Understandably, trainers will swear by particular items of gear for horses with certain tendencies, especially if that item was worn on the day of a horse’s best performance, even though there is no relevant empirical evidence.

More research needed

The scientific community has only recently begun to put ancient and modern theories on horse handling and training to the test in a bid to identify which techniques and devices work and why.

This discipline of equitation science is disclosing in research (involving one of us, Paul) how many horses are asymmetrical when racing.

An example of asymmetry is when a horse preferentially gallops with either the right or left leg leading. This has implications for the direction of the track which, for example, is clockwise in New South Wales and anticlockwise in Victoria.

Other research (also involving Paul) has looked at whether whips actually work on tired horses and how we can maximise our safety when working with horses.

Given time and the right level of funding, equitation scientists will use evidence from the years of racing records to show what works best and what doesn’t. Until then, we must trust trainers to prioritise their horses’ welfare when making selections from the register of approved gear.

This story originally appeared on The Conversation. It was authored by Professor Paul McGreevy and PhD candidate Cathrynne Henshall from the University of Sydney School of Veterinary Science.