THIS PAGE FIRST POSTED 11 JANUARY 2016

LAST MODIFIED Monday 15 September 2025 7:53

A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs

Dr GRAEME SKINNER (University of Sydney) and Dr JIM WAFER (University of Newcastle)

THIS PAGE IS ALWAYS UNDER CONSTRUCTION

To cite this:

Graeme Skinner (University of Sydney) and Jim Wafer (University of Newcastle),

"A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs",

Australharmony (an online resource toward the early history of music in colonial Australia):

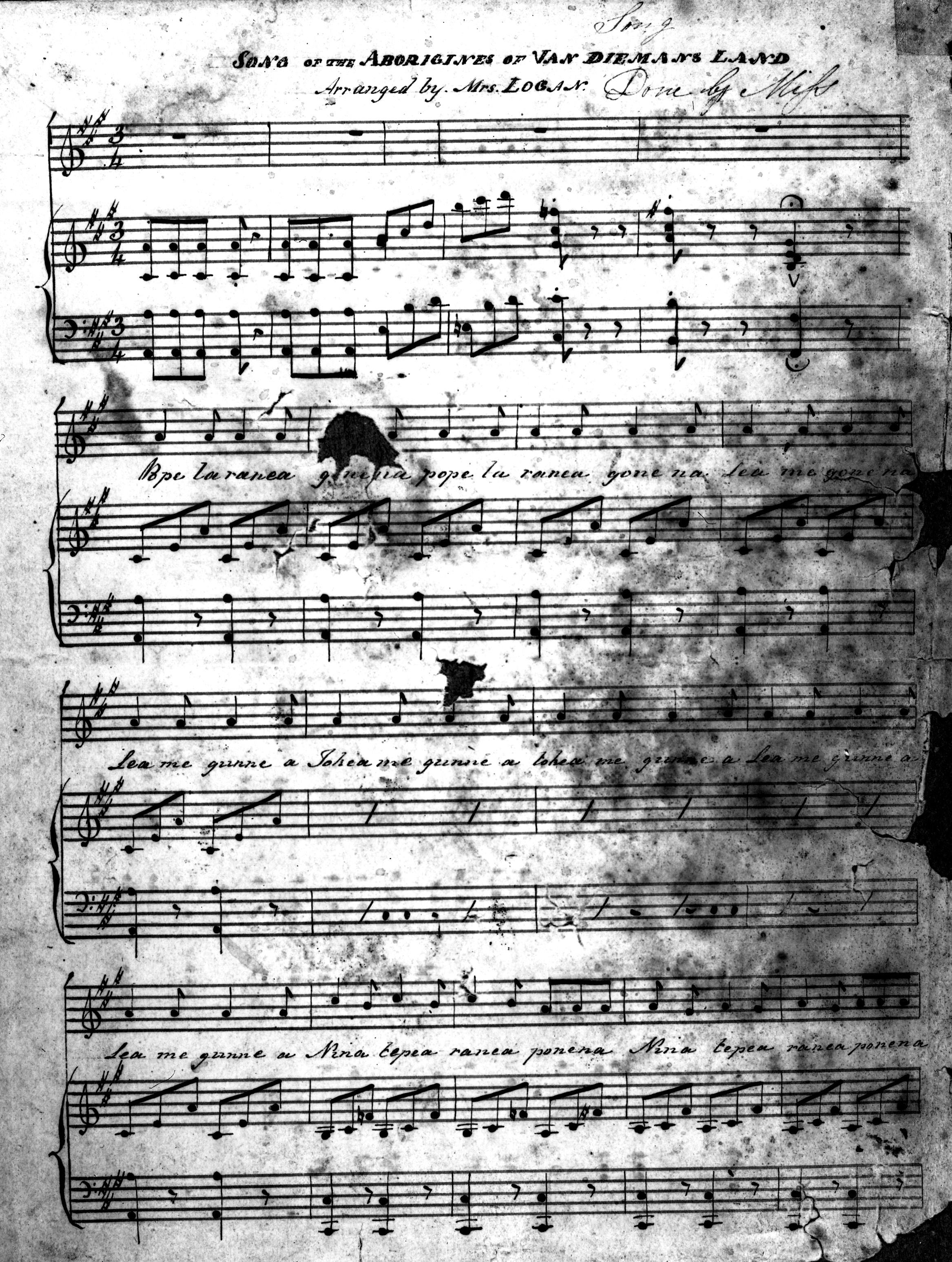

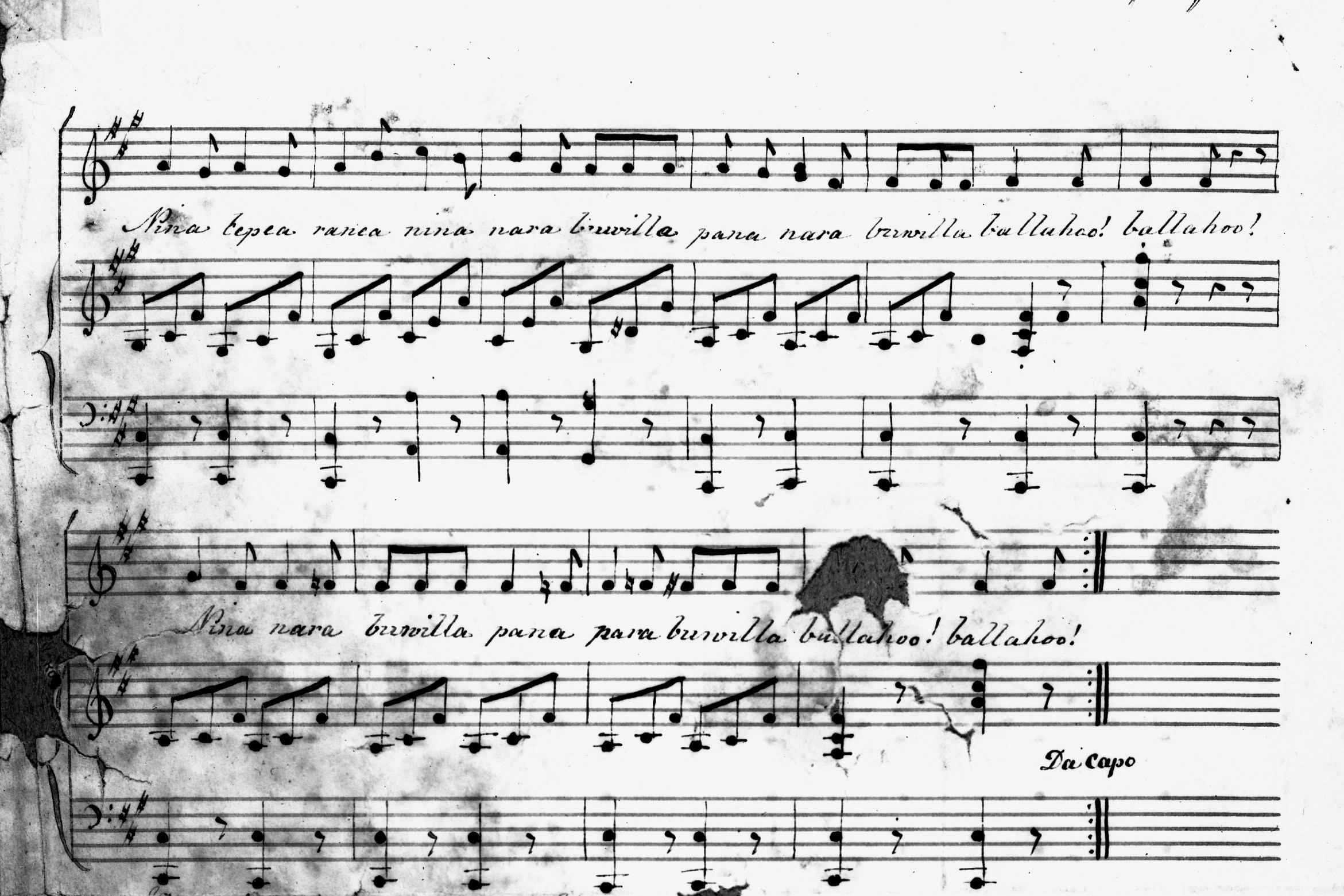

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php; accessed 11 February 2026

Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders are respectfully advised that this page and links contain names, images, and voices of dead persons.

We acknowledge and pay respect to the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. It is upon their ancestral lands, and in respectful emulation of their example, that Australharmony is built and maintained.

Development of this checklist was assisted by funding and infrastructure support from Professor Linda Barwick (Associate Dean Research in 2016), Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney; and the Sydney Unit of PARADISEC (Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures).

Contents of this page (click on blue hyperlinks)

Linguistic data (notes by J. W.)

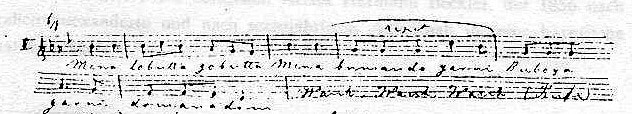

1 1 song call (Dharug) (Cooee), collected c.1789-1802, Sydney area NSW, published Lesueur and Petit 1824

2 1 song (Dharug) (Barrabula), c.1790-93, Sydney area NSW, Jones 1811

3 2 songs (Dharug), 1802, Sydney area NSW, Lesueur and Petit 1824

4 1 song (Dharug) (Wahabindeh), c.1800-05, Sydney area NSW, unidentified UK print, c.1805-10

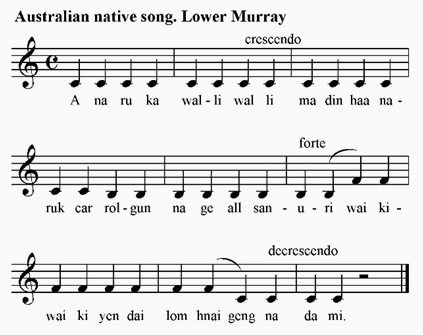

5 2 songs (Dharug), 1819, Sydney area NSW, Freycinet 1839

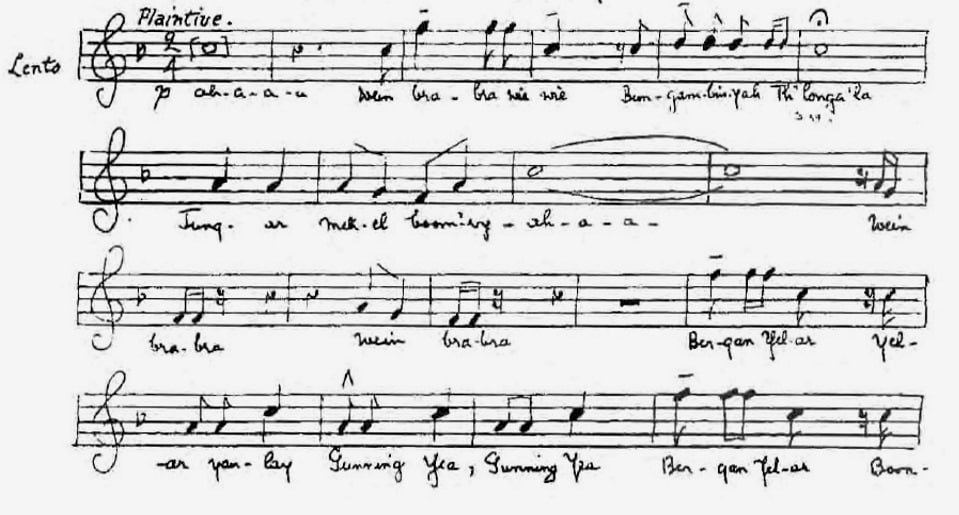

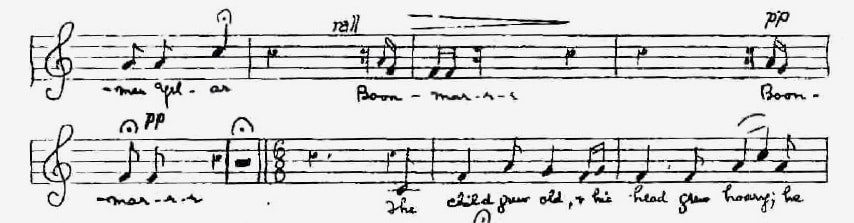

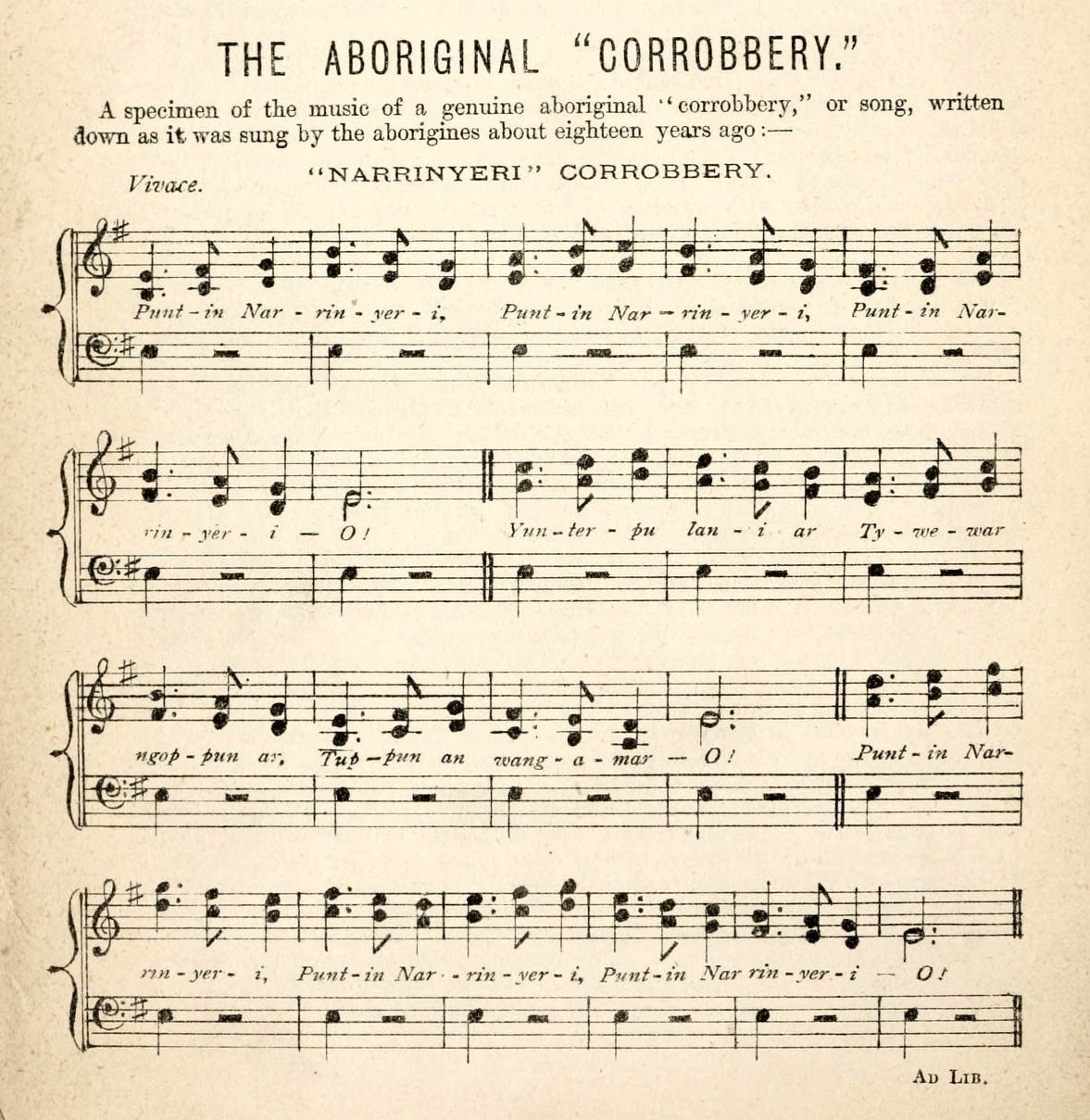

6 1 song (Dharug) (Harry's song), c.1820, Sydney area, NSW, Field 1823

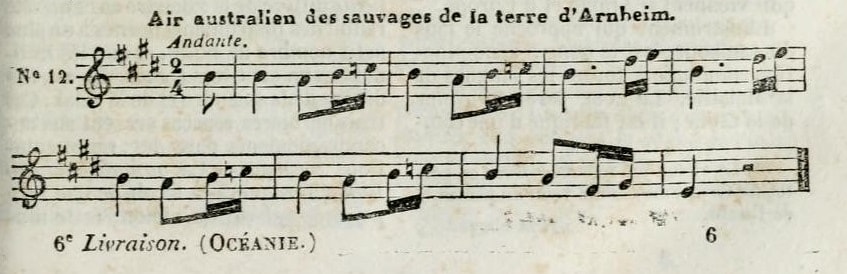

7 1 song (Arnhem Land), by 1830, Arnhem Land NT, Domeny de Rienzi 1836

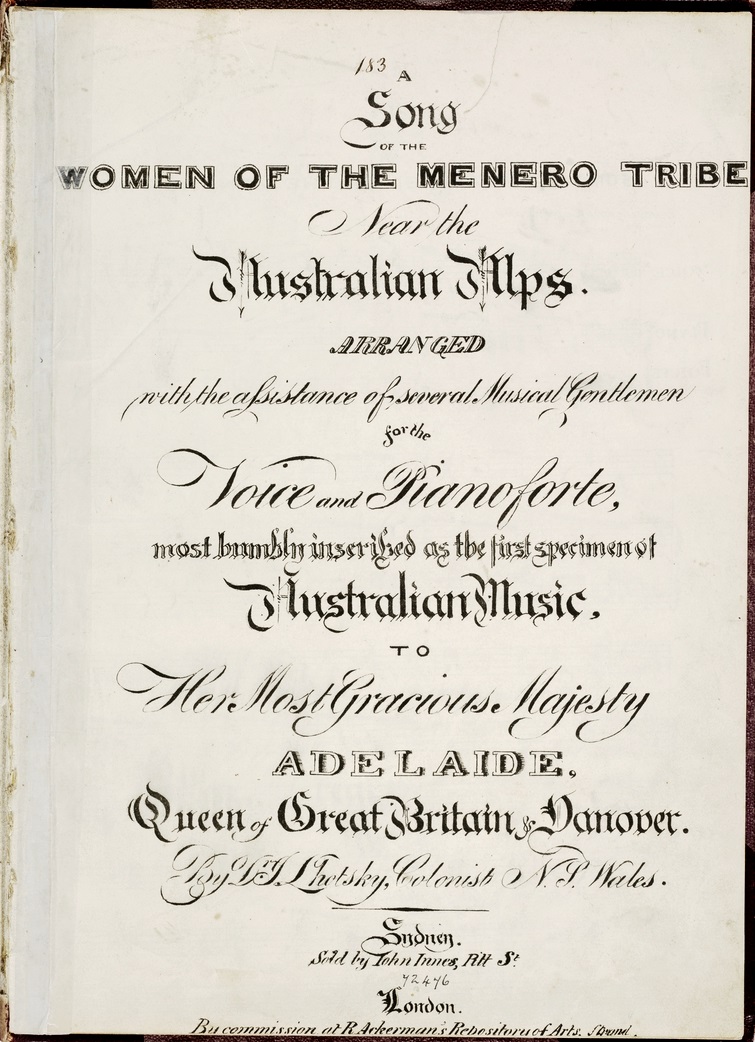

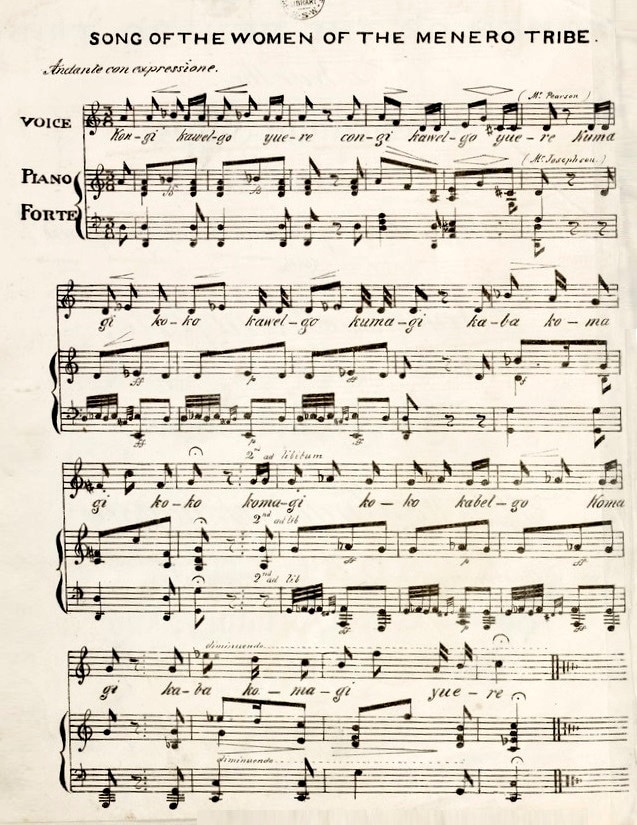

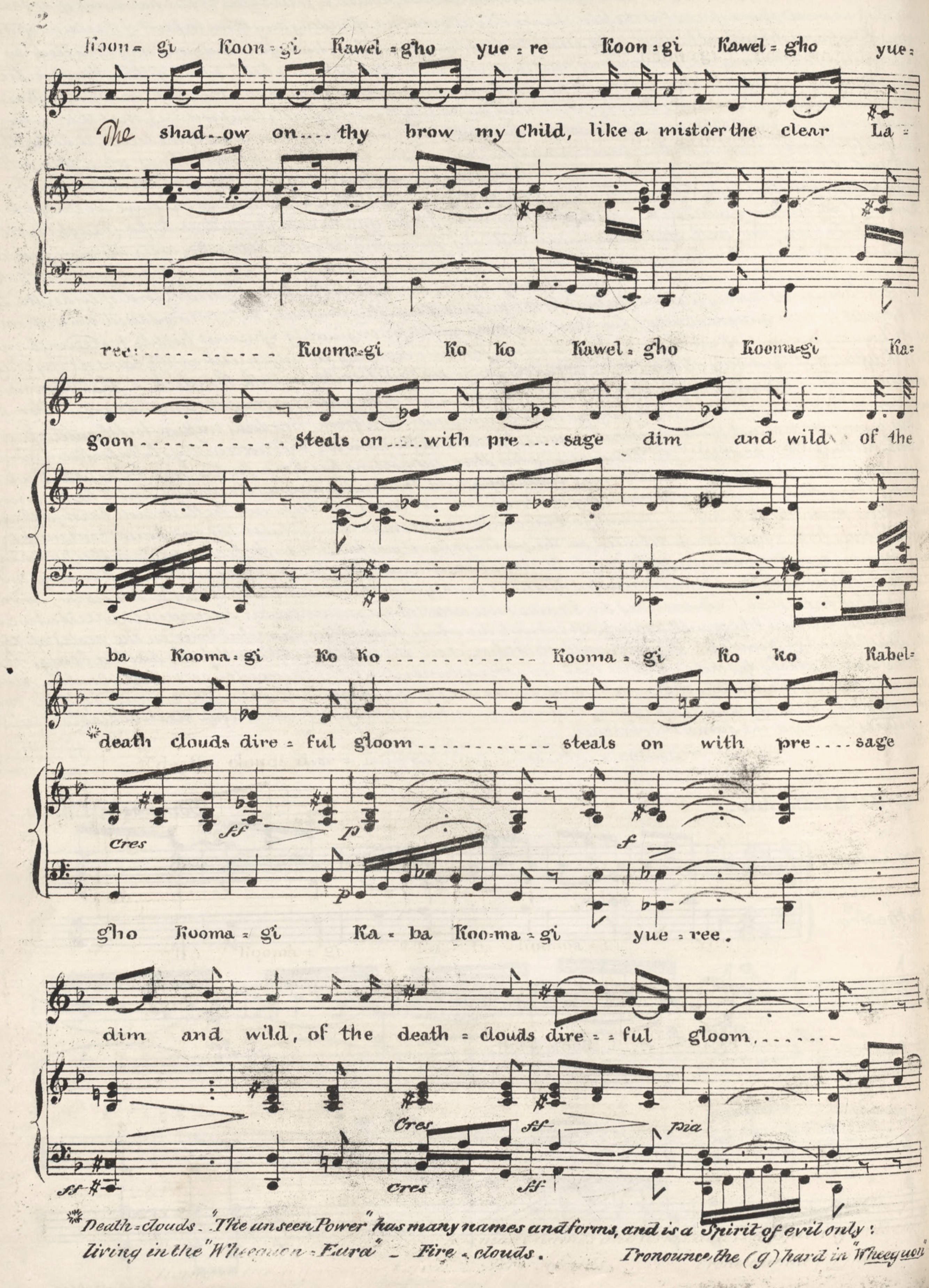

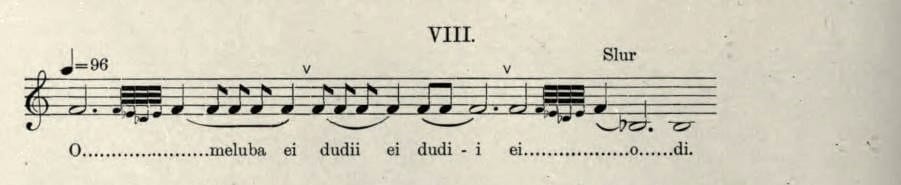

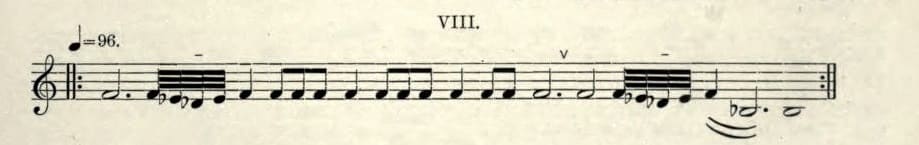

8 1 song (Ngarigu) (Kongi kawelgo), 1834, South-east NSW, Lhotsky 1834

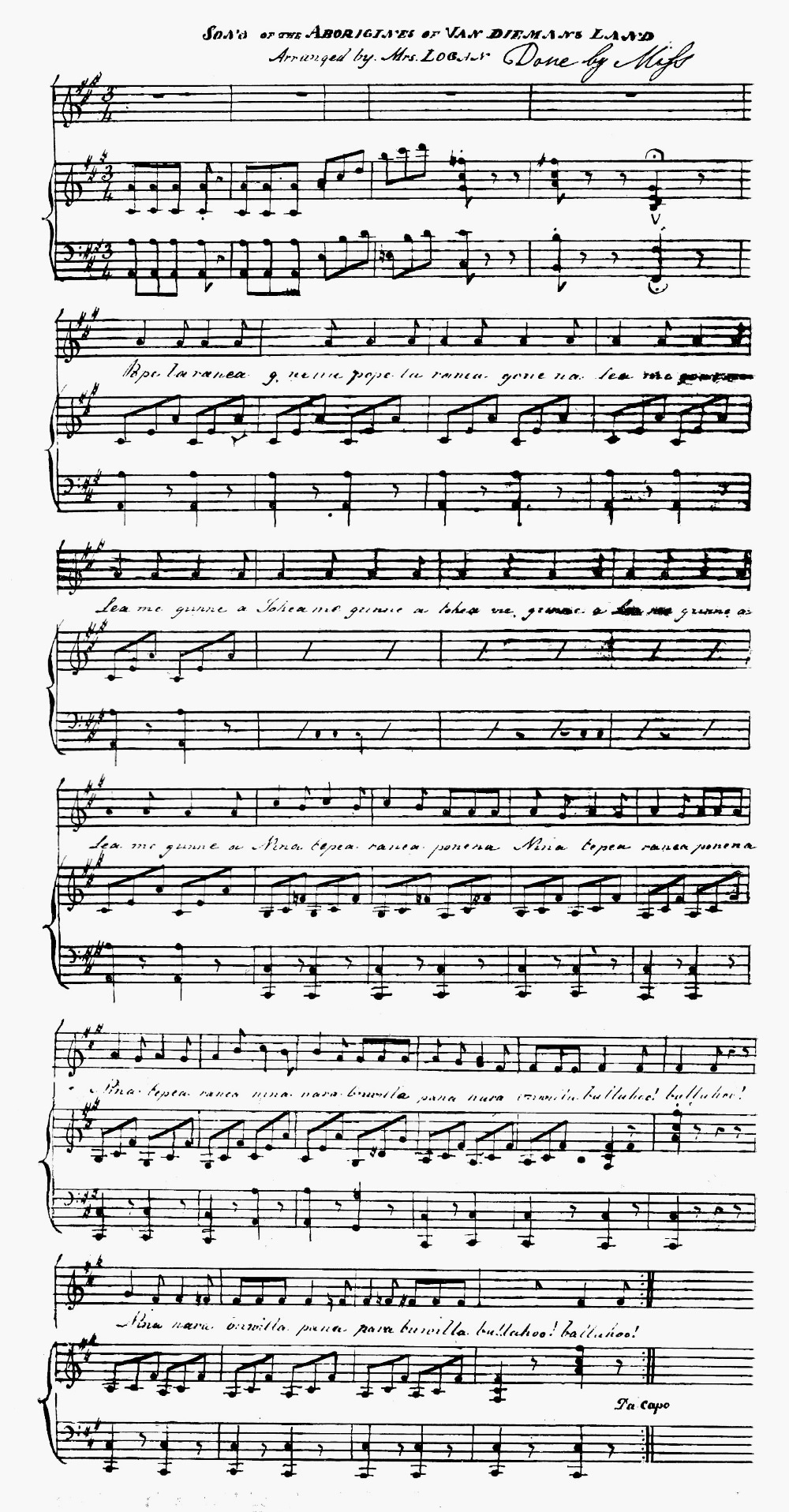

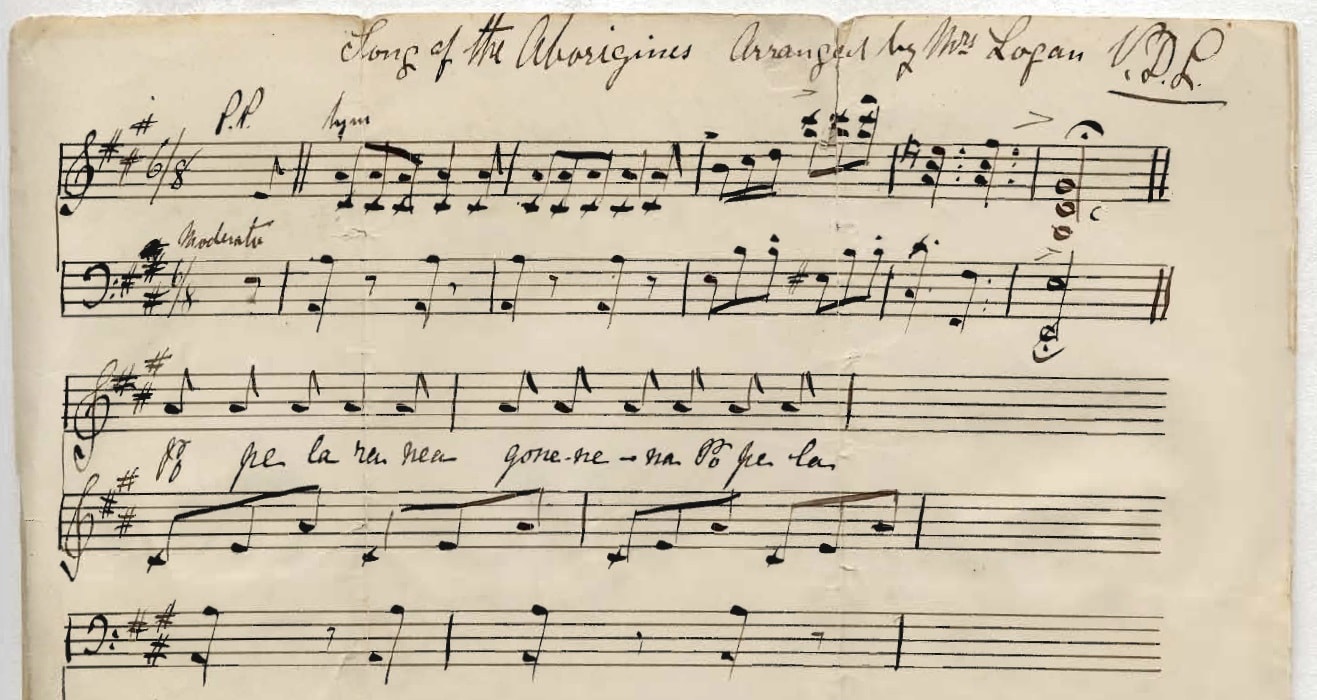

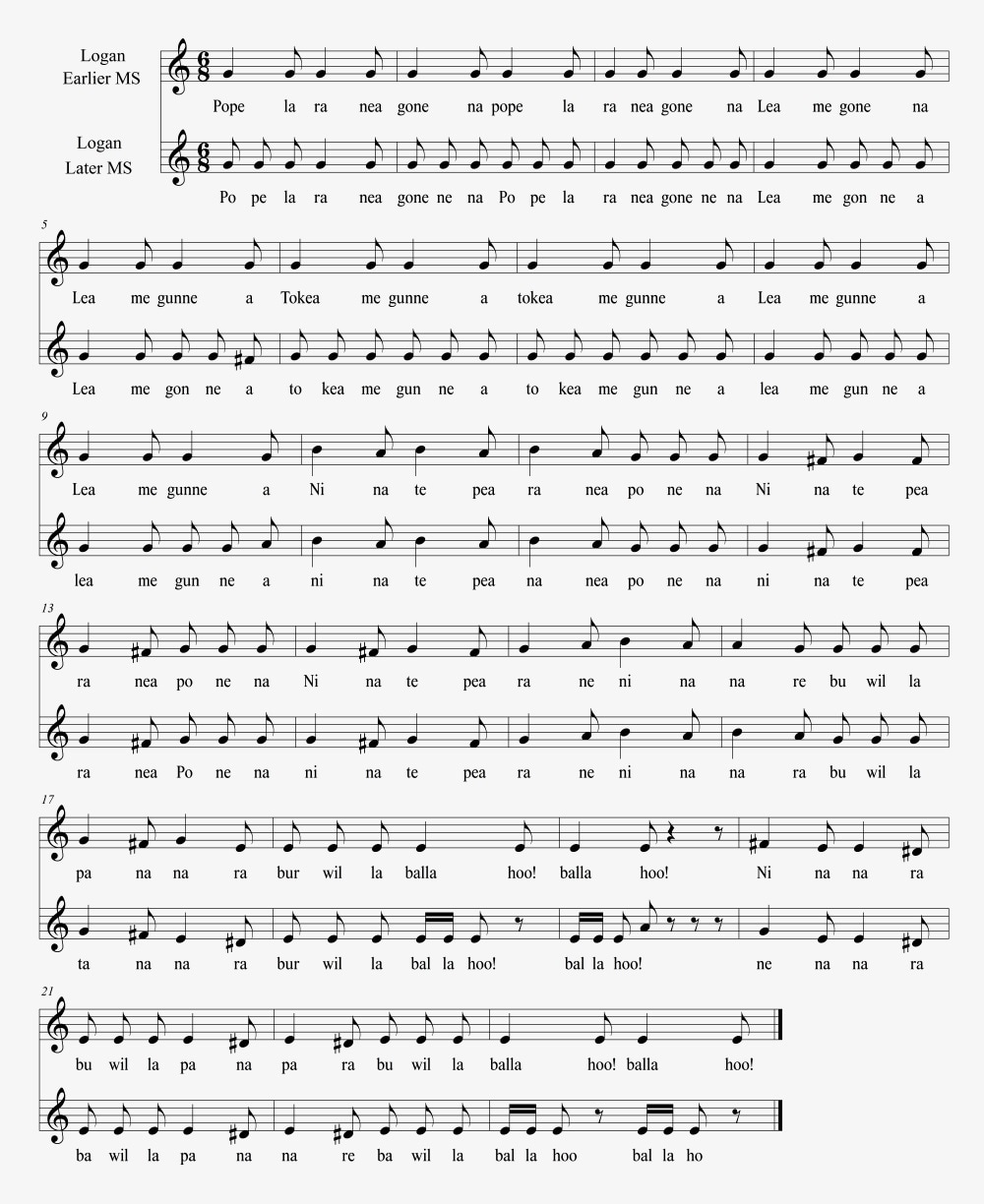

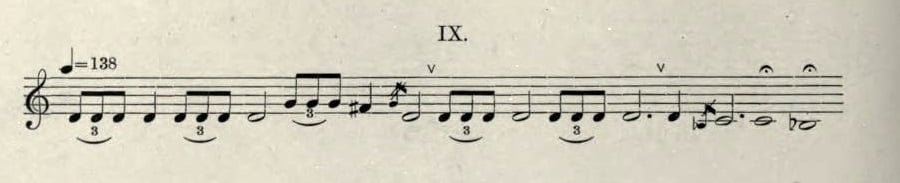

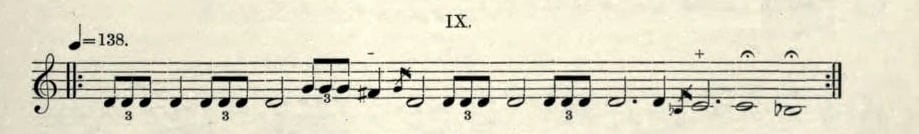

9 1 song (Tasmanian) (Popela), 1831-36, Hobart area TAS, MSS 1840s & 1890s

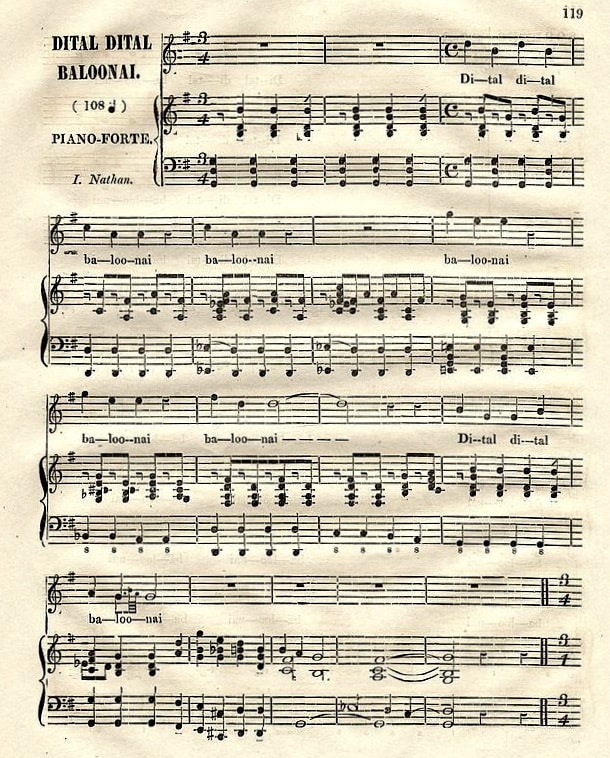

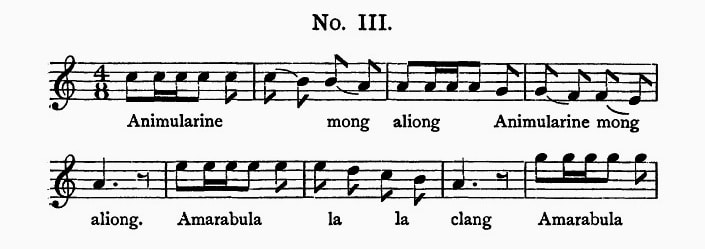

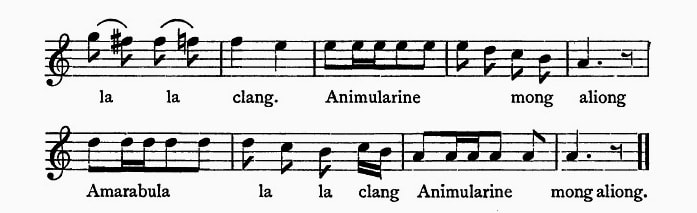

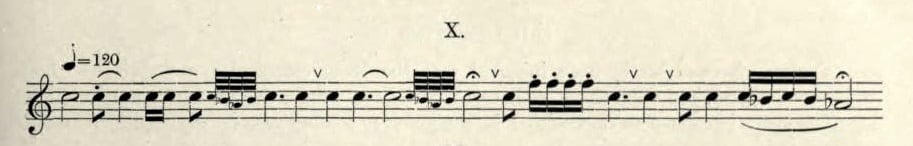

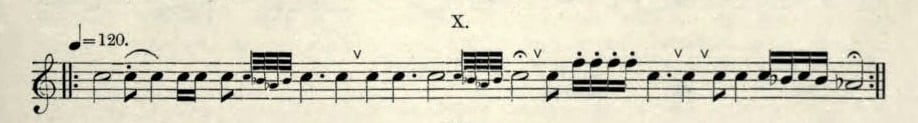

10 2 songs (Ngarigu) (Monaro), c.1836-38, South east NSW, Nathan 1842 & 1848-49

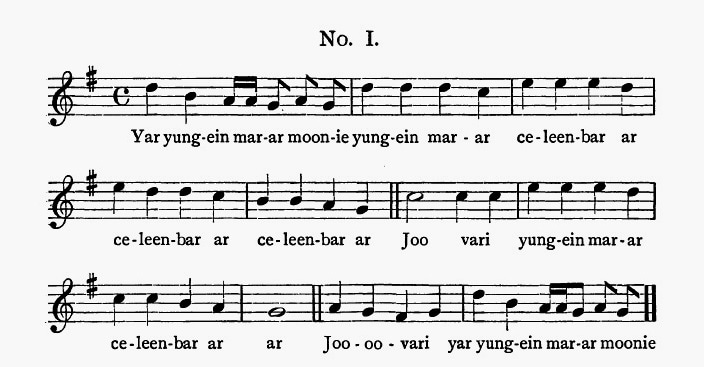

11 3 songs (Dharug), 1839, Sydney area NSW, Wilkes 1845

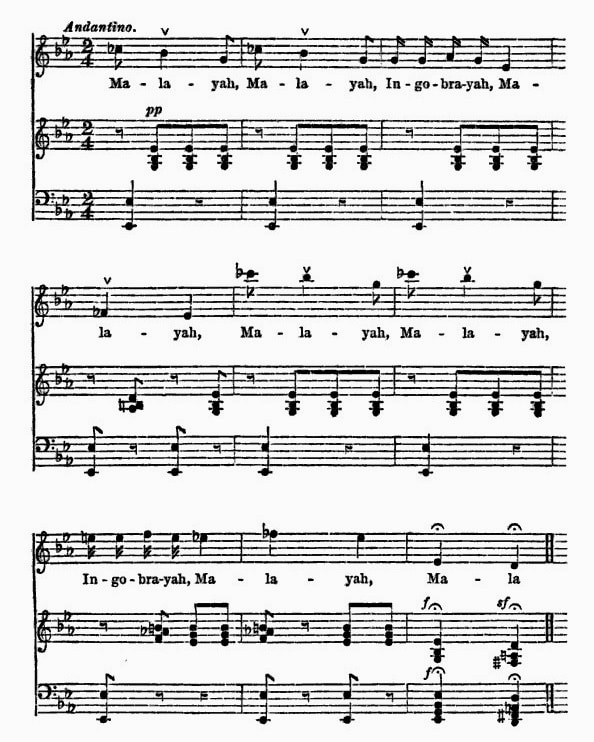

12 1 song (Yuin) (Malayah), c.1845, South coast NSW, Townsend 1849

13 2 songs (Wiradjuri),, by 1848, Wellington Valley NSW, Nathan 1848-49

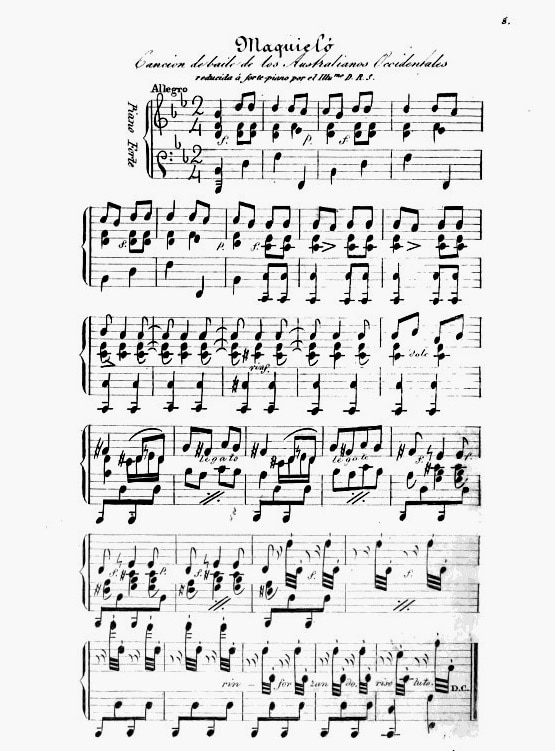

14 1 song (Nyungar) (Maquielo), c.1846-48, South west WA, Salvado 1853

15 1 song (Wiradjuri), c.1840s-80s, Upper Murray NSW, MS

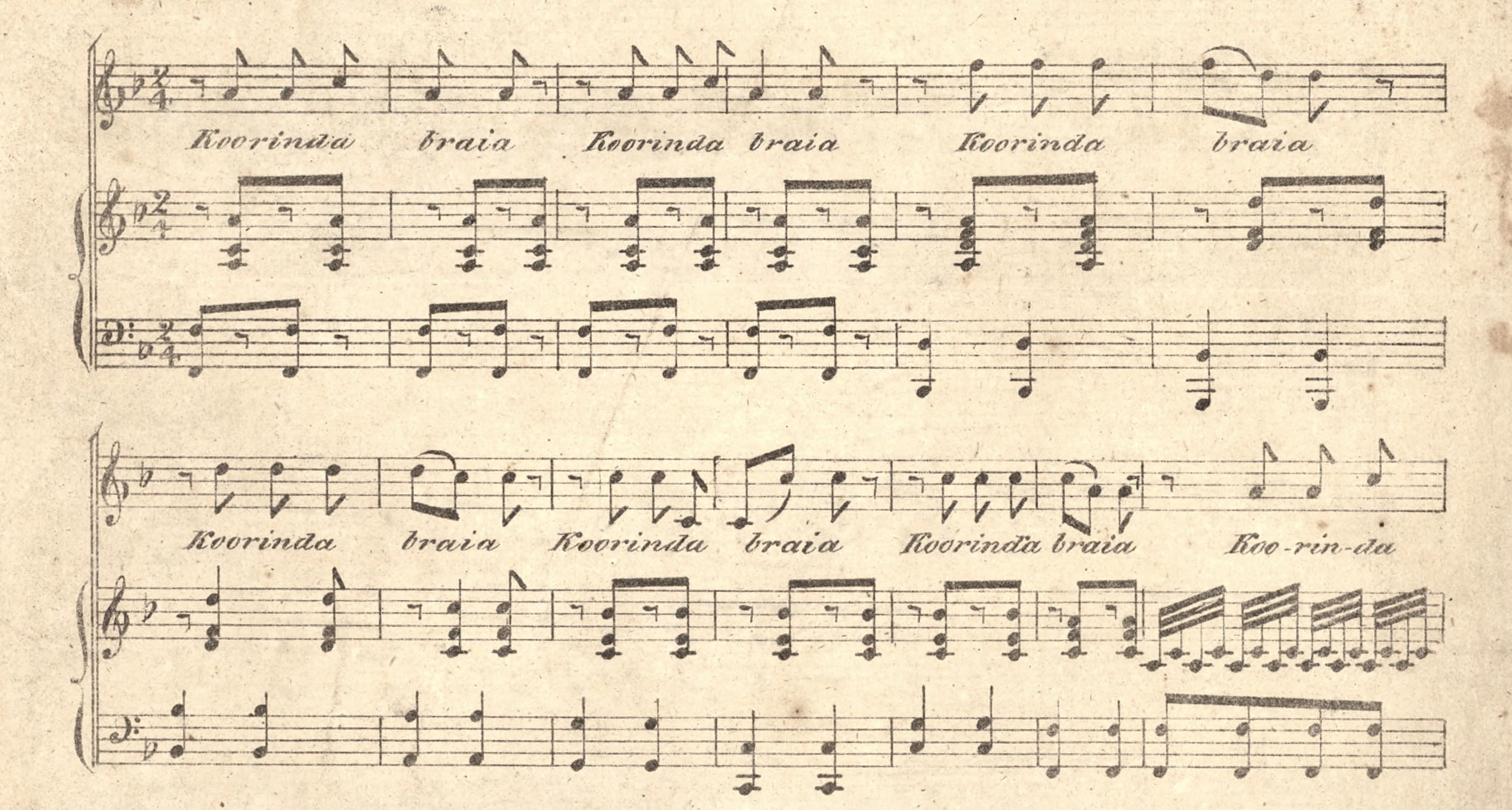

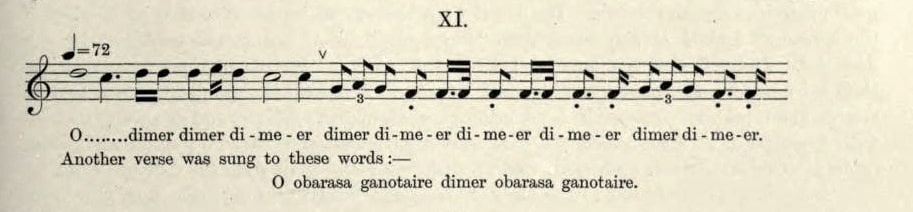

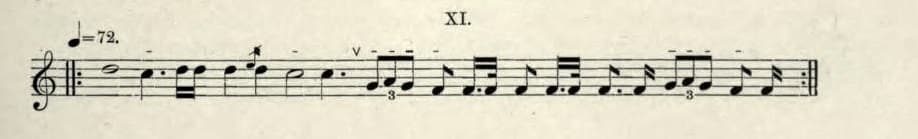

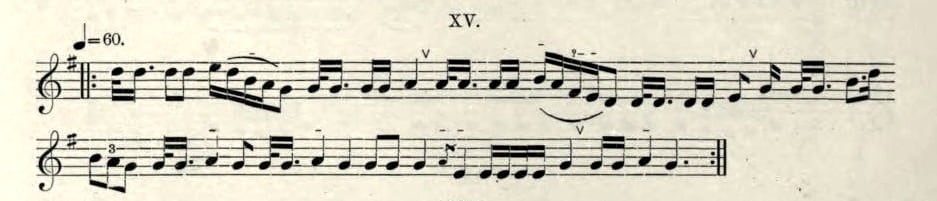

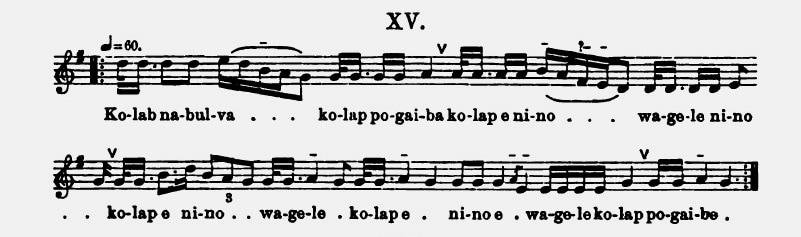

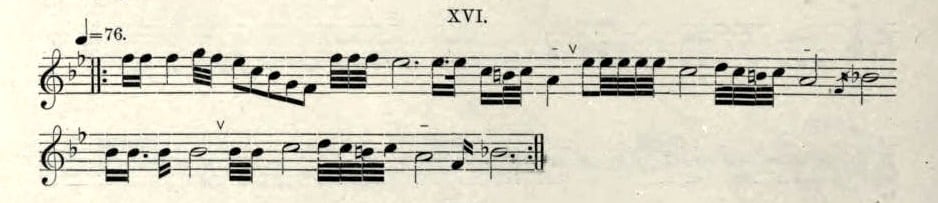

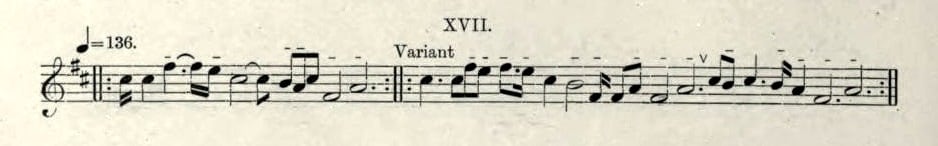

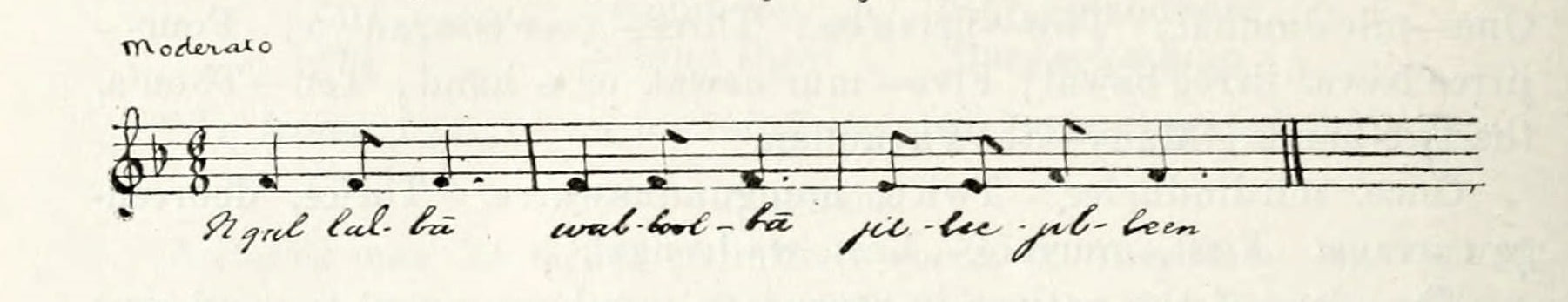

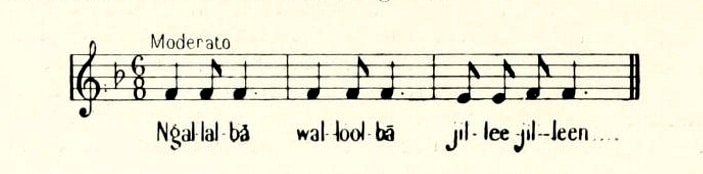

16 2 songs (Yagara), c.1840-50, Brisbane district QLD, Petrie 1904

17 1 song (Nyungar), c.1850, South west WA, Chauncy 1878

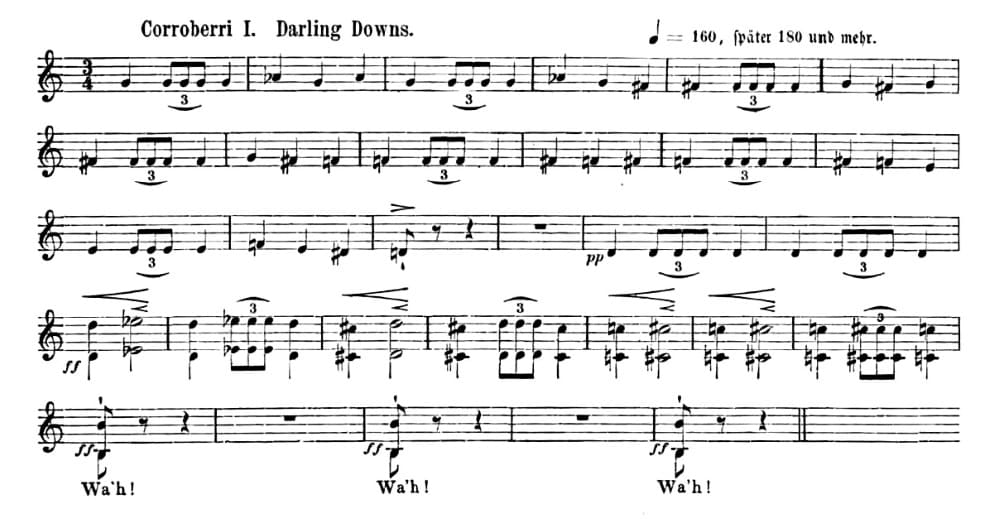

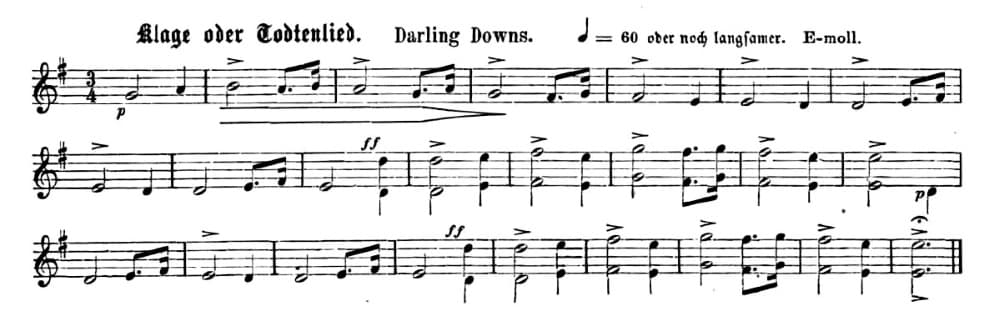

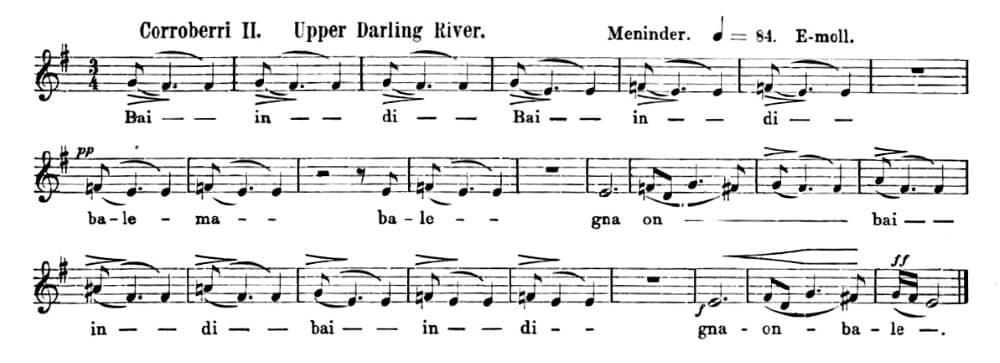

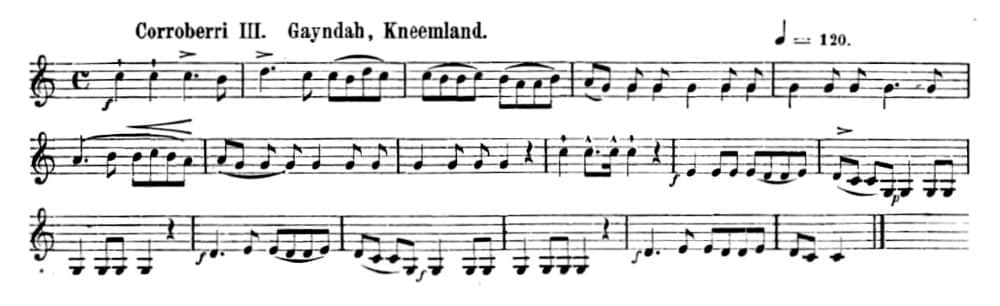

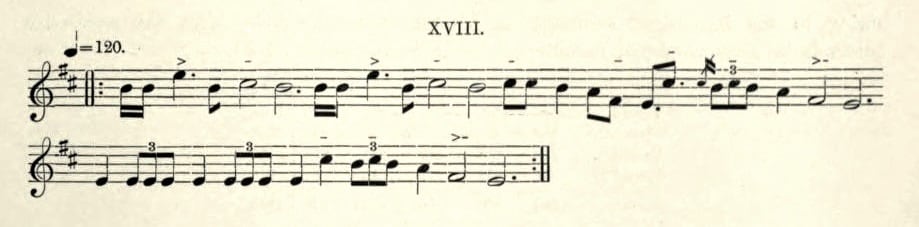

18 7 songs (Queensland), 1858-61, Darling Downs QLD, Beckler 1868 & MS

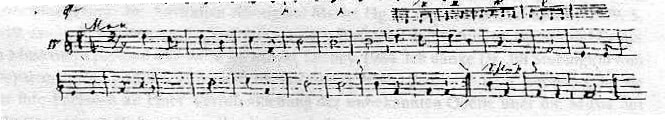

19 1 song (Paakantyi) (Anaruka), 1860, Far west NSW, MS

20 1 song (Narrinyeri), c.1861, South east SA, Taplin 1879

21 4 songs (Gureng-Gureng), c.1863-65, Central QLD, Marett 1910

22 4 songs (Uutaalnganu) (Anco), 1858-75, Cape York Peninsula QLD, Merland 1876

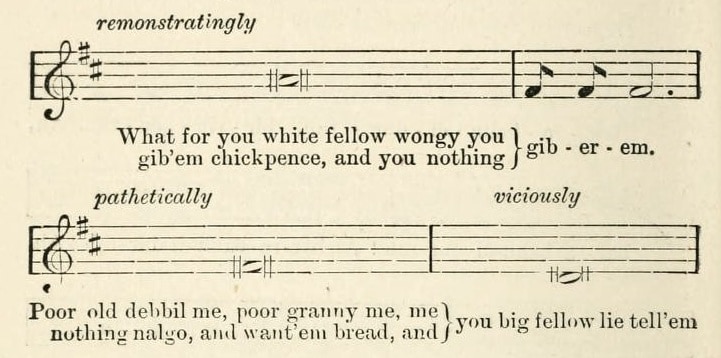

23 2 songs (Gabi gabi), c.1865-1884, Central QLD, Mathew 1887

24 3 songs (Queensland), 1882-83, North QLD, Lumholtz 1889

25 3 songs (Kulin) (Barak), c.1840-c.1885, Southern VIC, Torrance 1887

26 1 song (Torres Strait) (Saw-fish), 1888, Torres Strait QLD, Haddon 1890

27 5 songs (Maric), c.1890-c.1900, South east QLD, Lethbridge and Loam 1937

28 4 songs (Nyungar), c.1893, South west WA, Calvert 1894

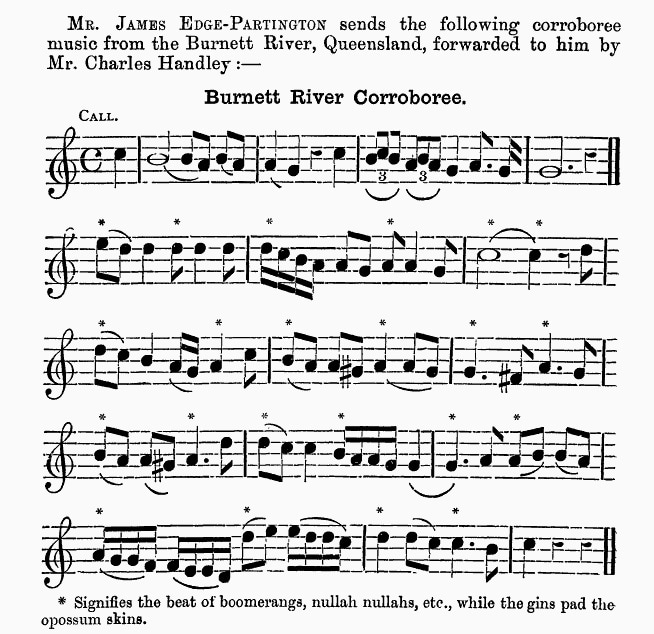

29 1 song (Waka-Kabic) (Burnett River), by c.1895, Central QLD, Handley 1897

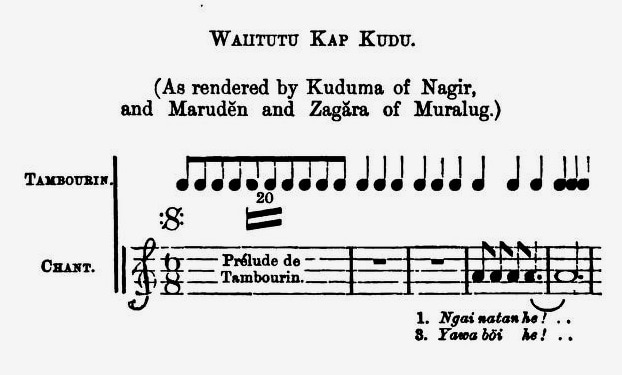

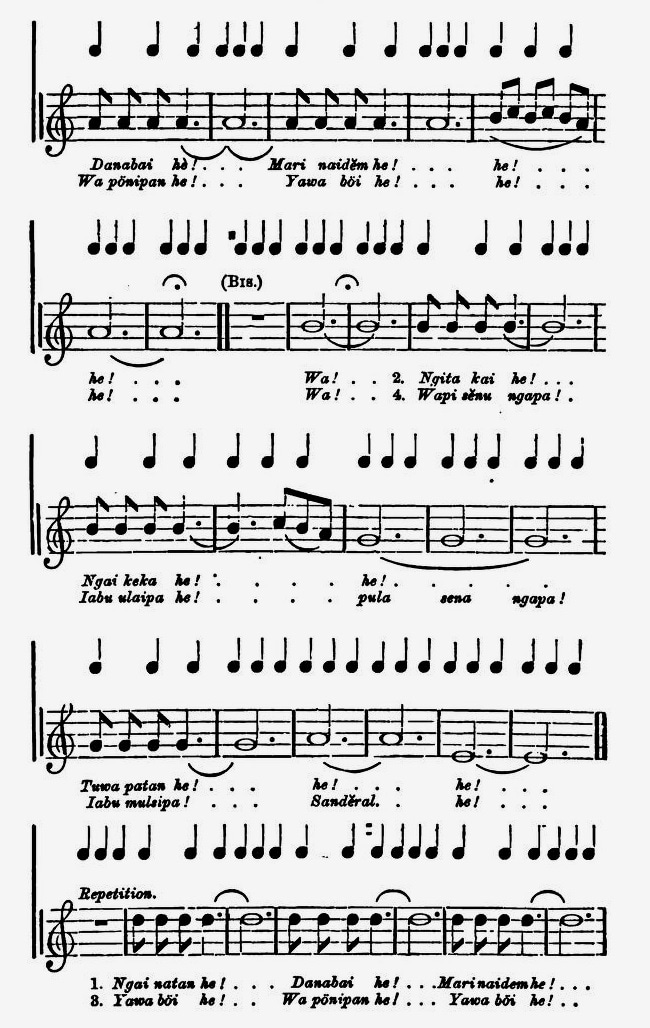

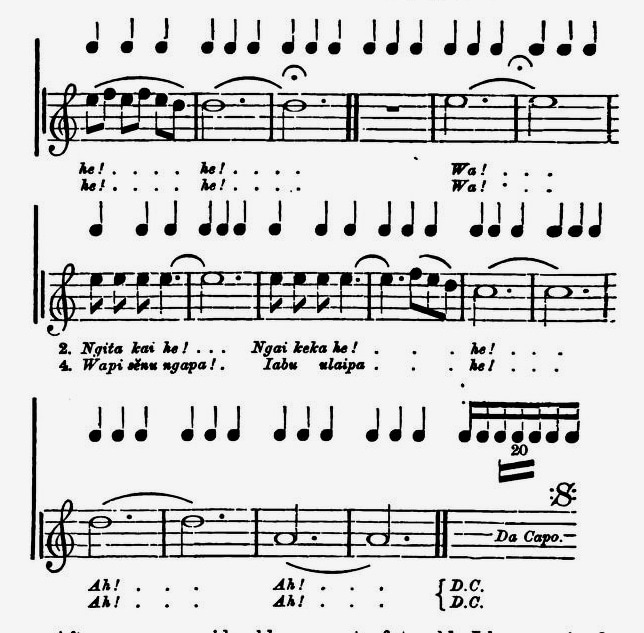

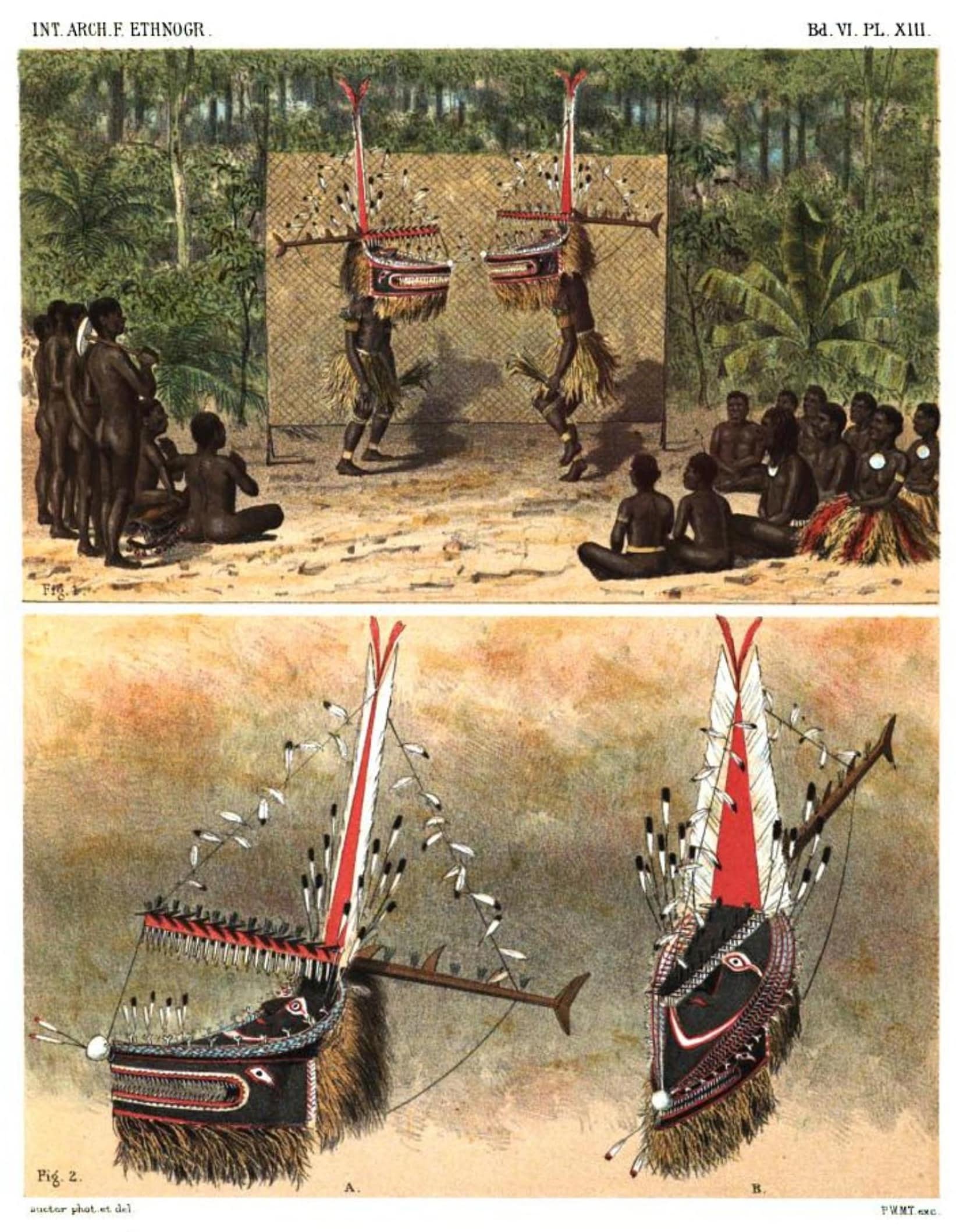

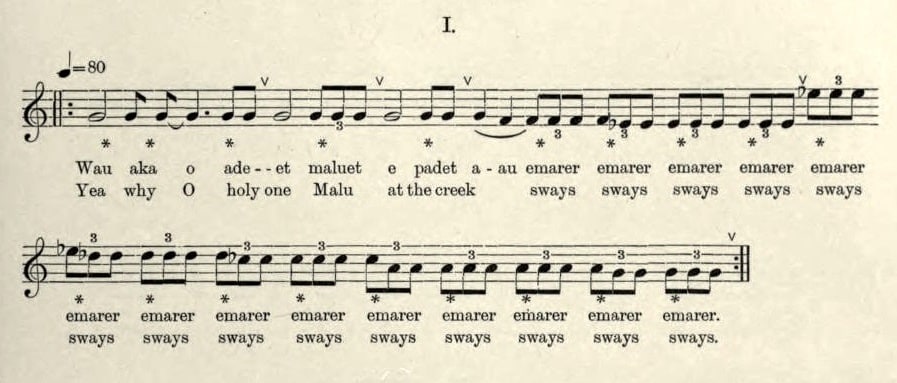

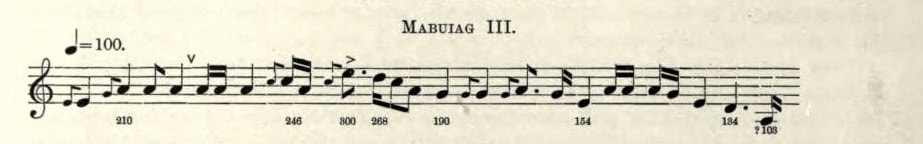

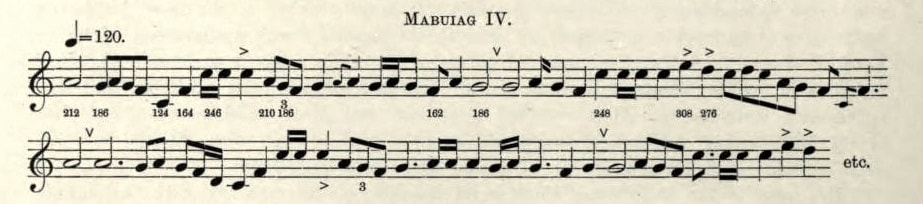

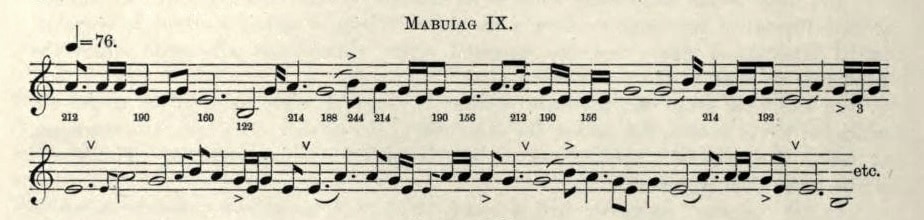

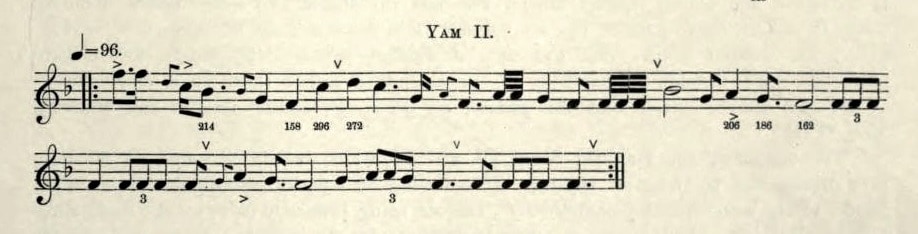

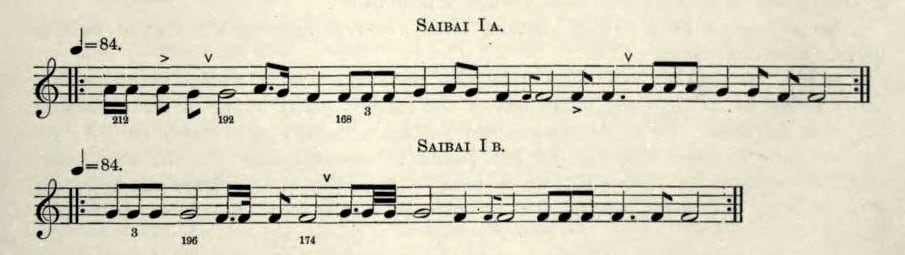

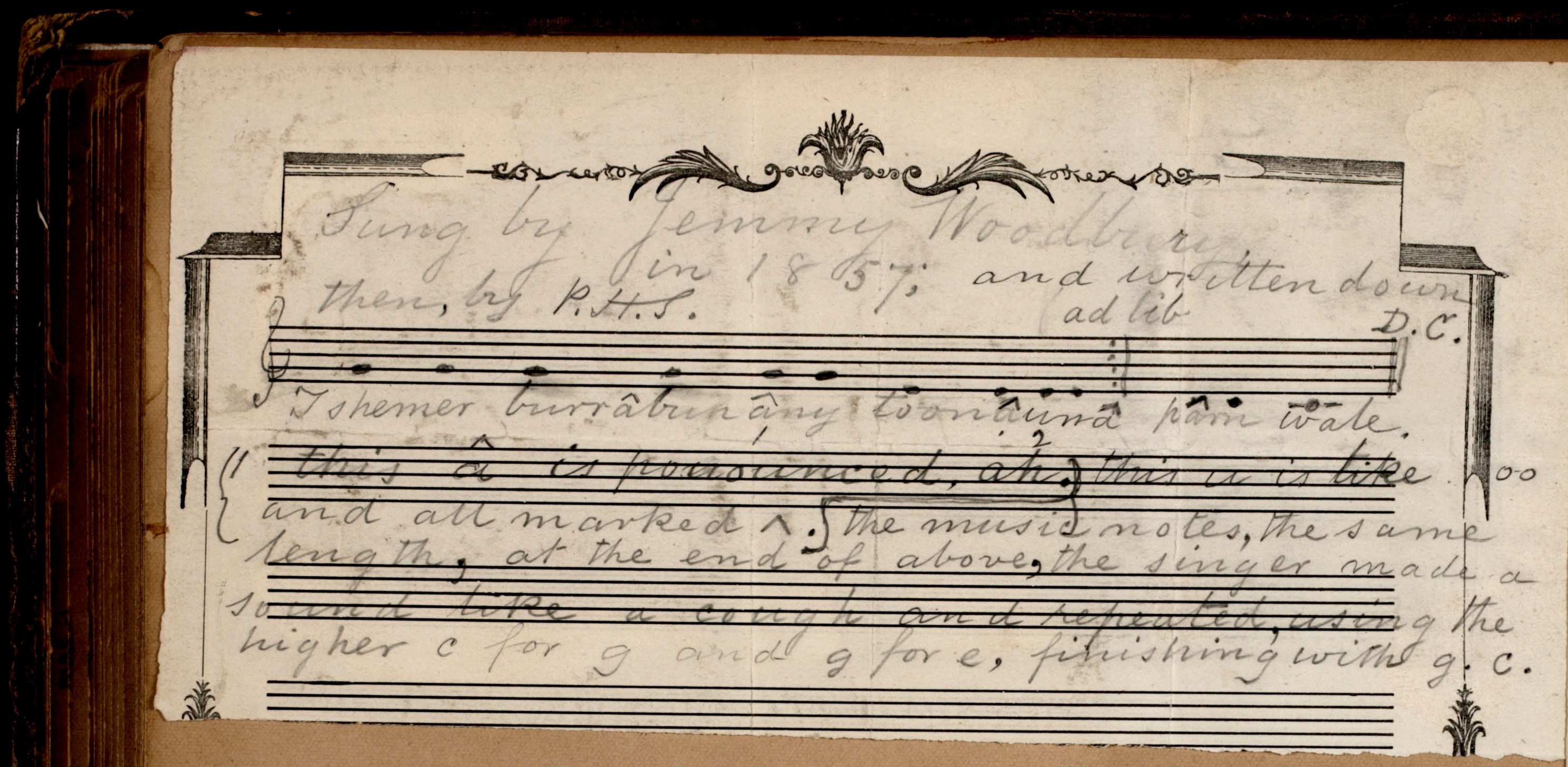

30 28 songs (Torres Strait), 1898, Torres Strait QLD, recordings 1898

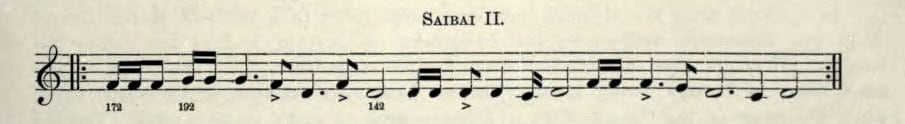

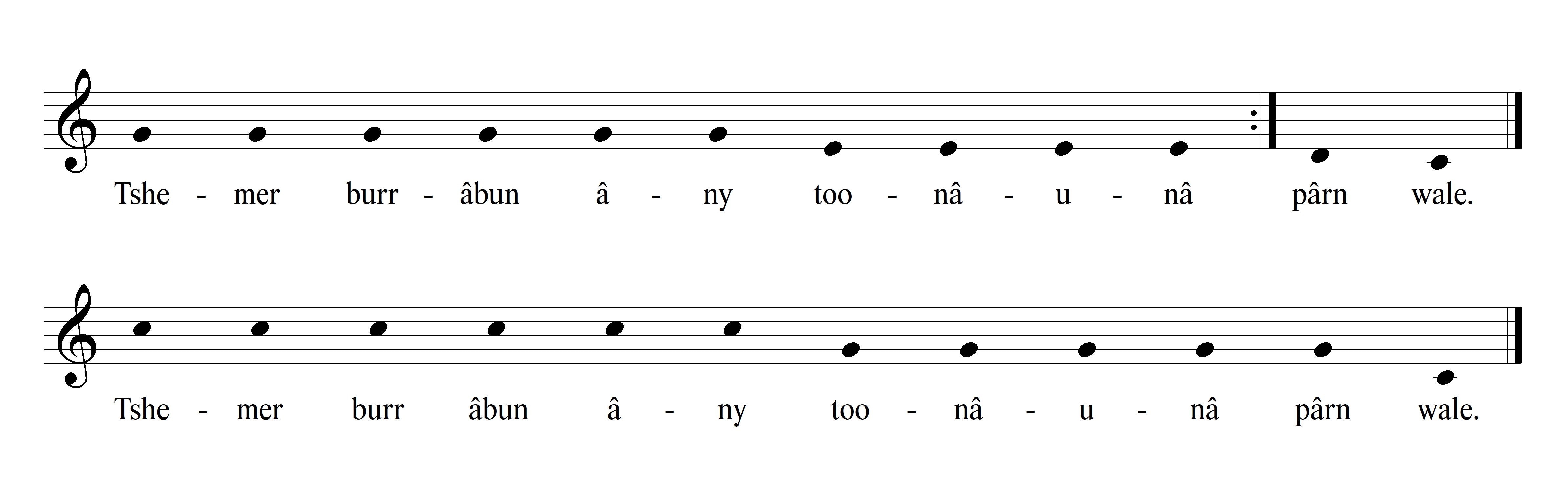

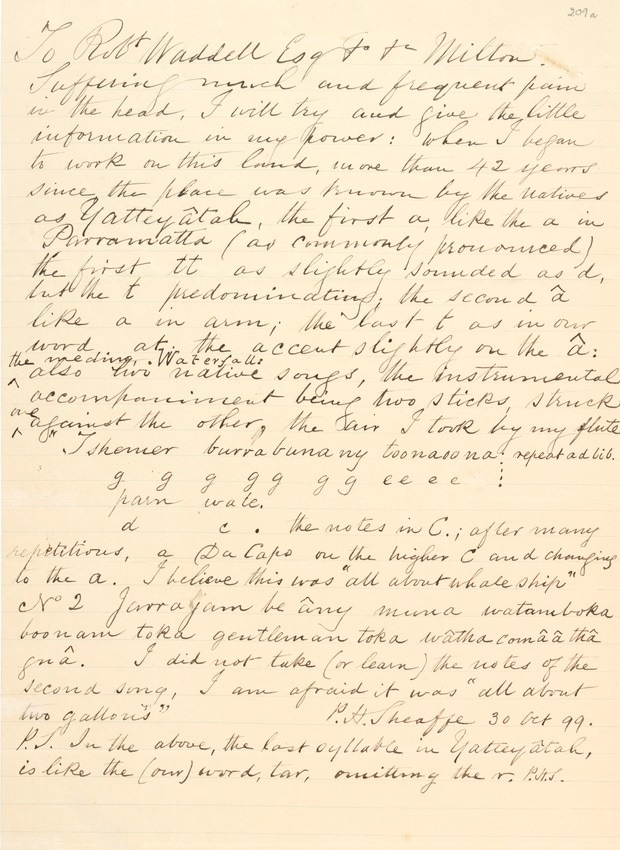

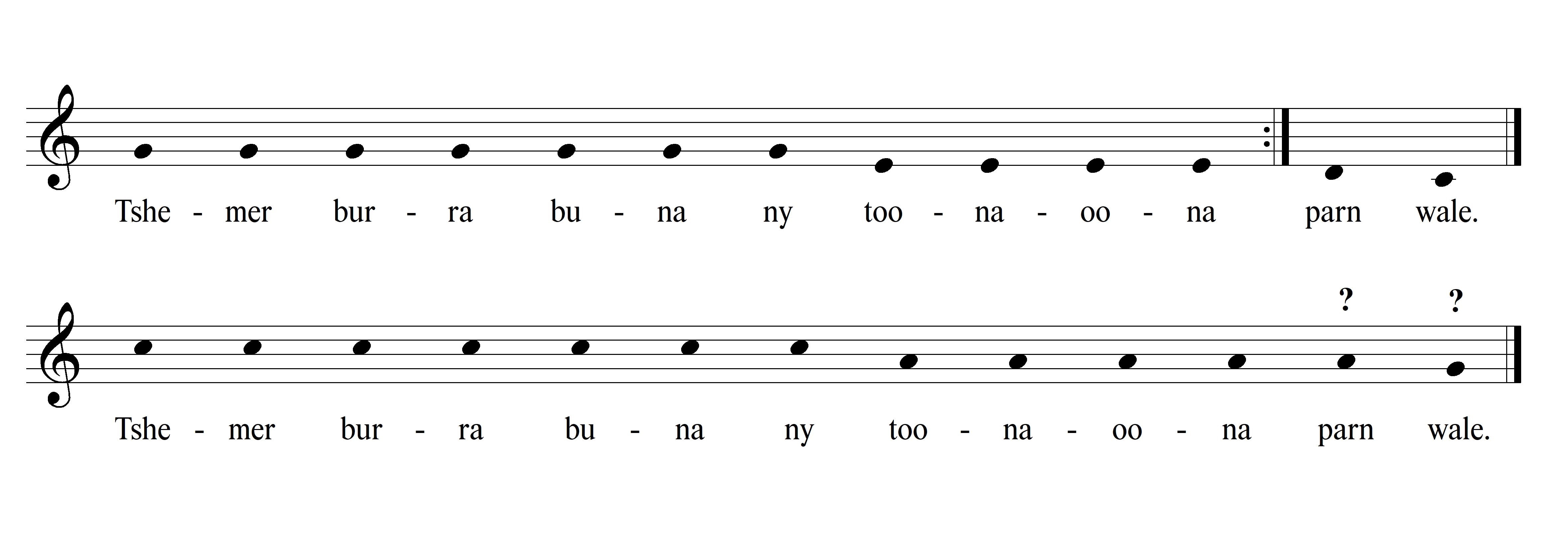

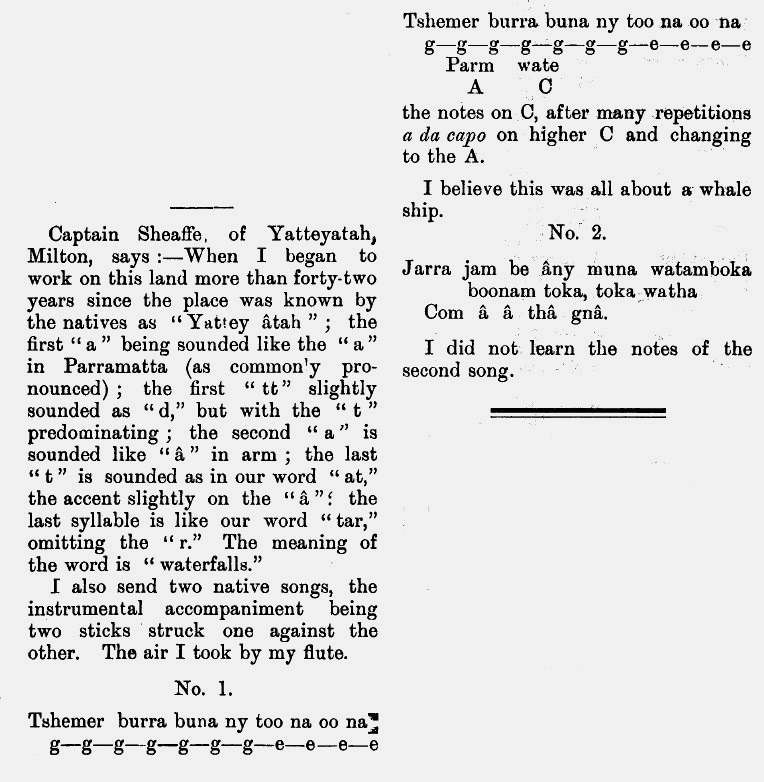

31 1 song (Yuin) (Tshemer burra), 1899, South coast NSW, MS Sheaffe

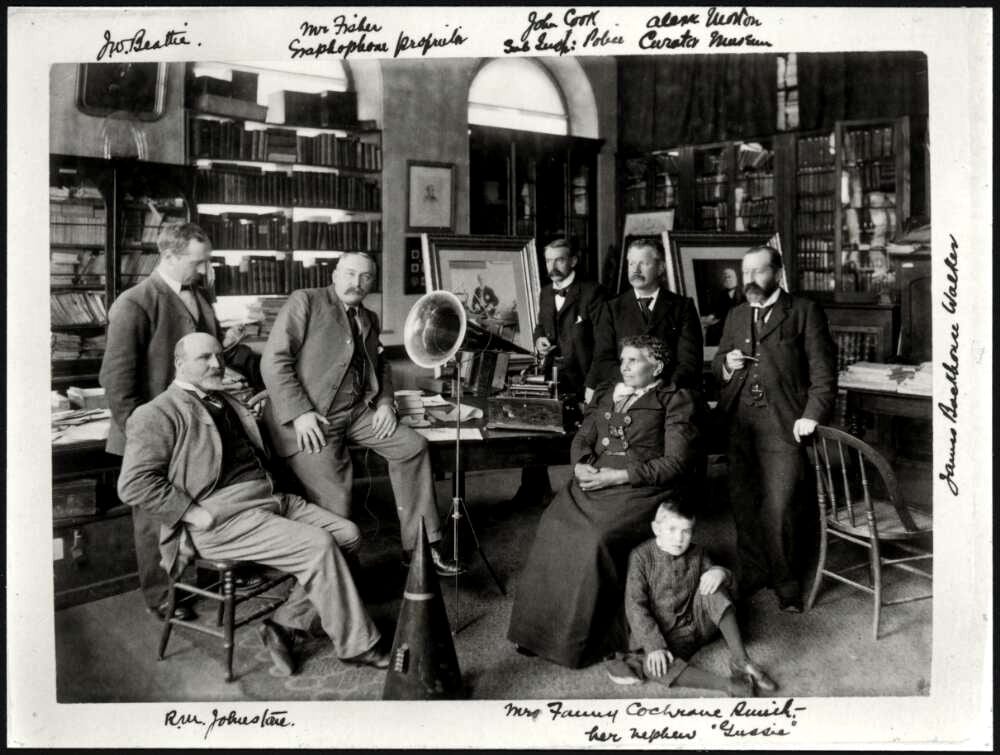

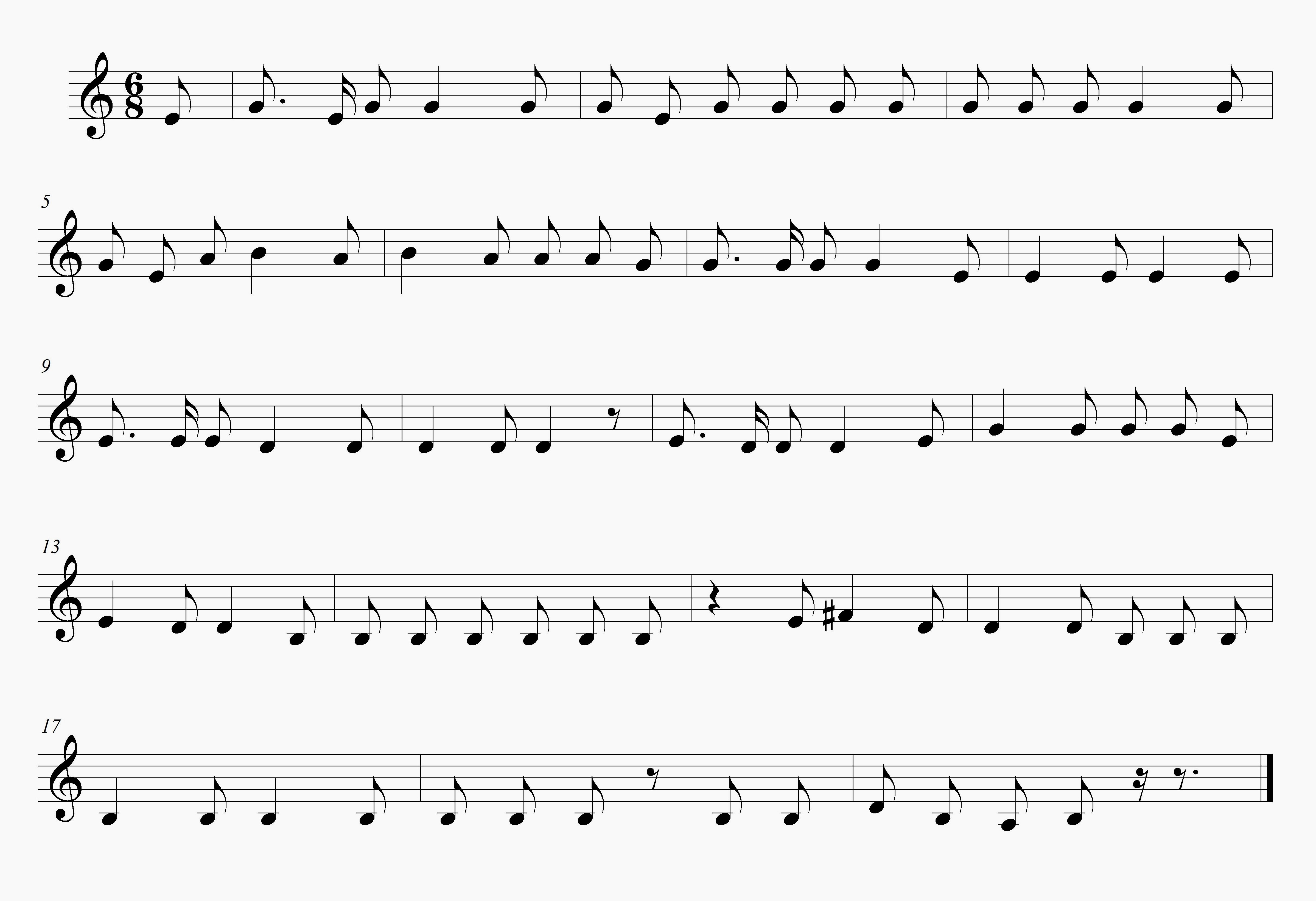

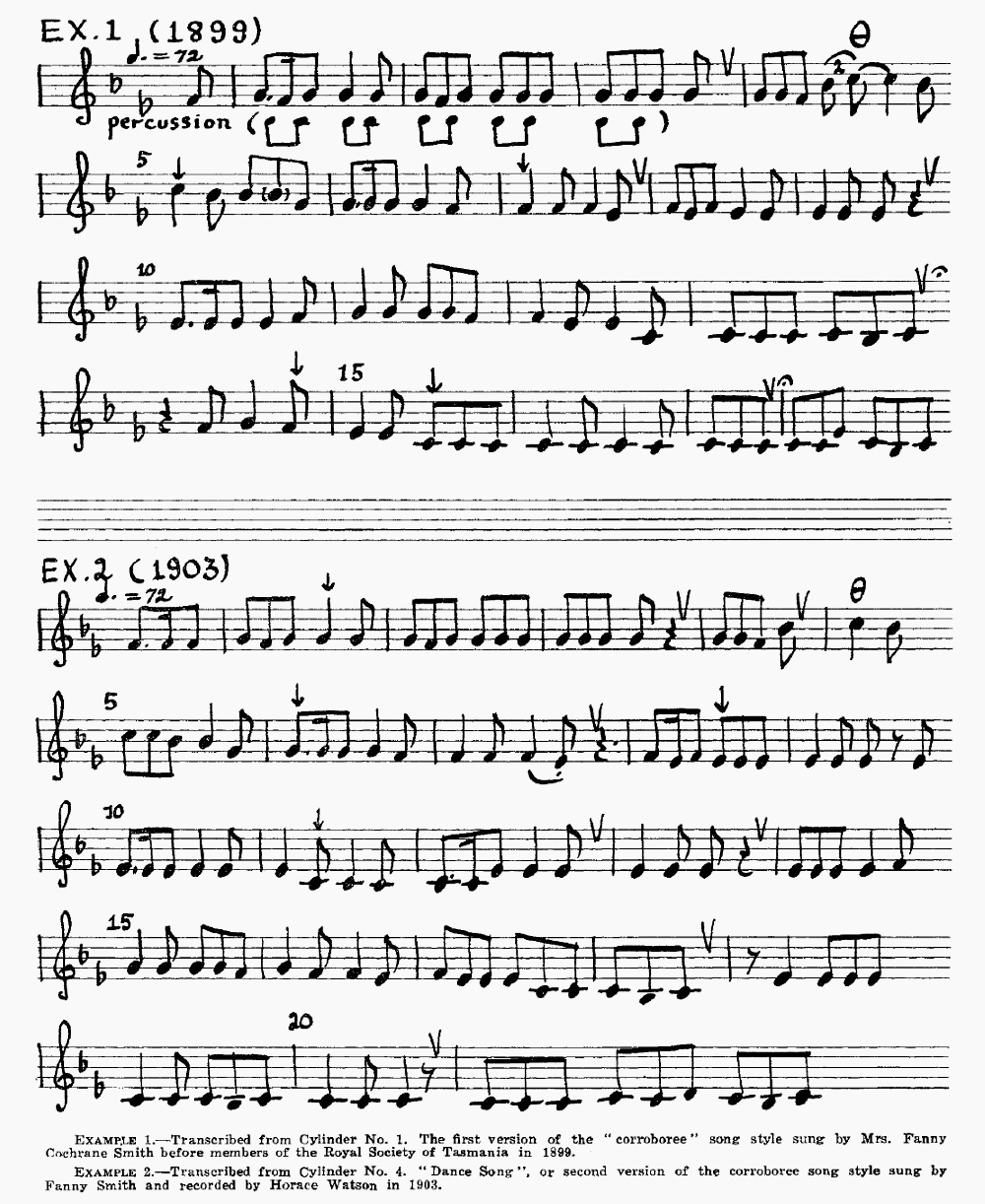

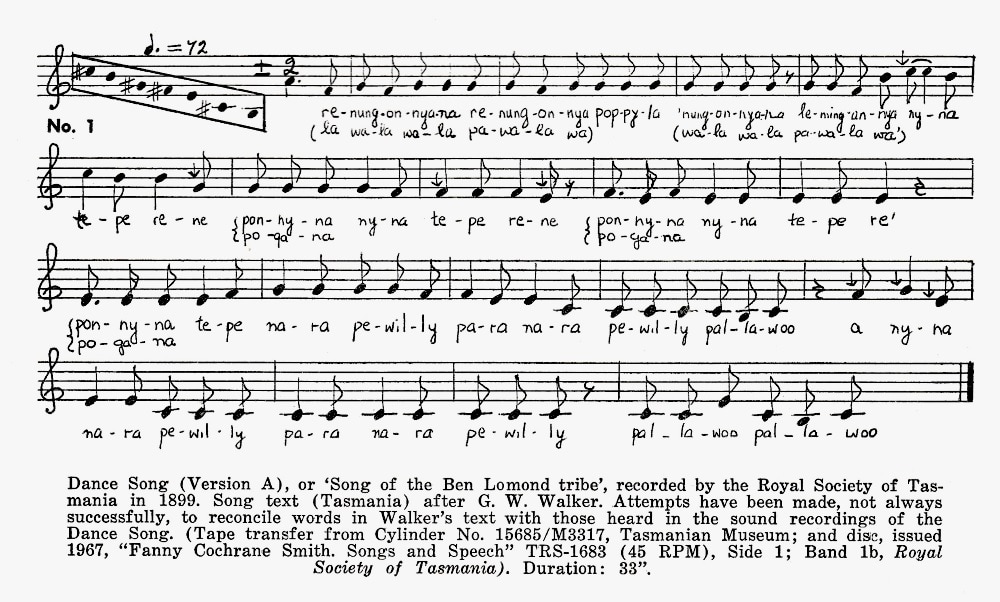

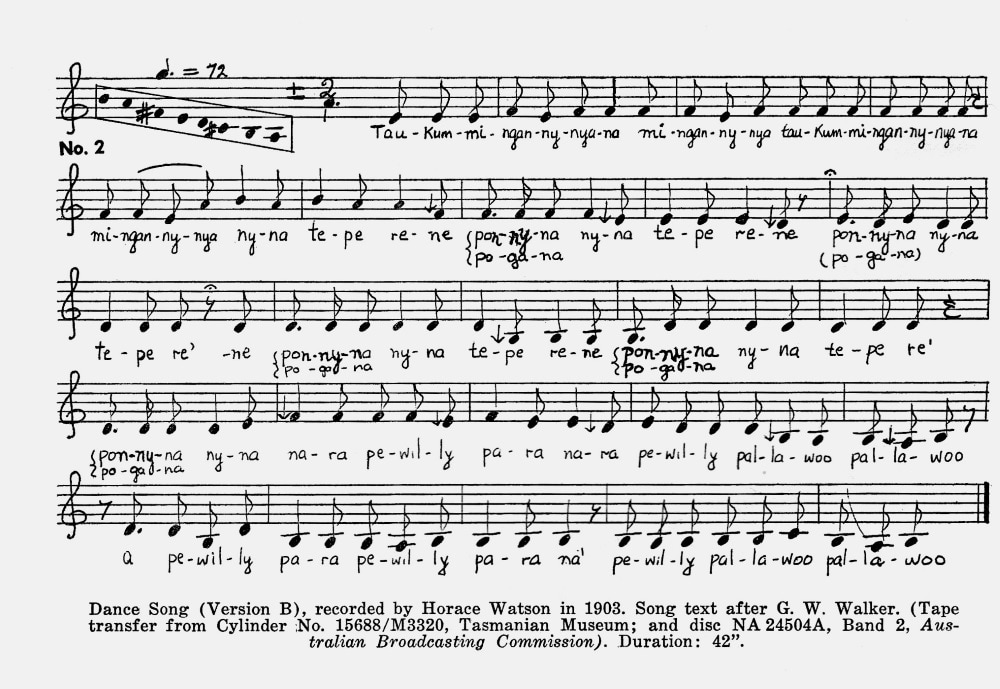

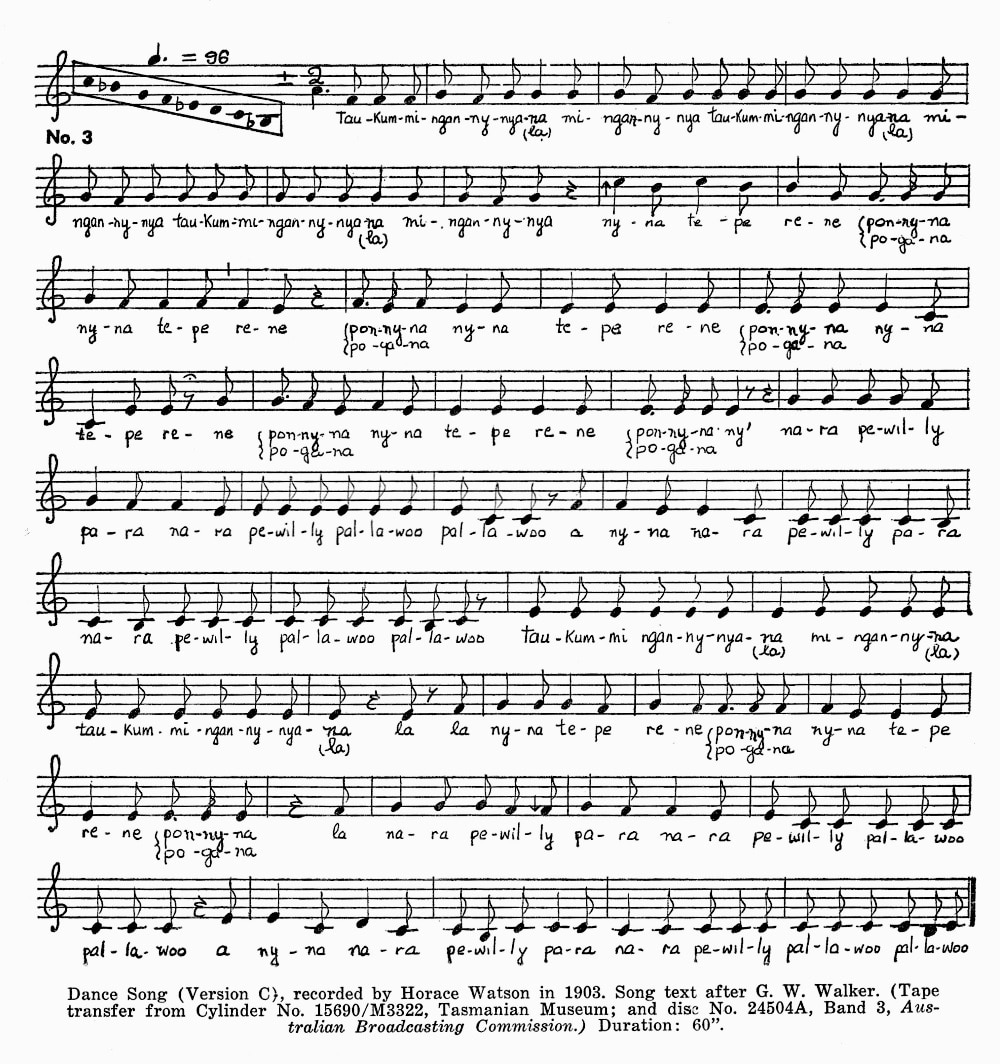

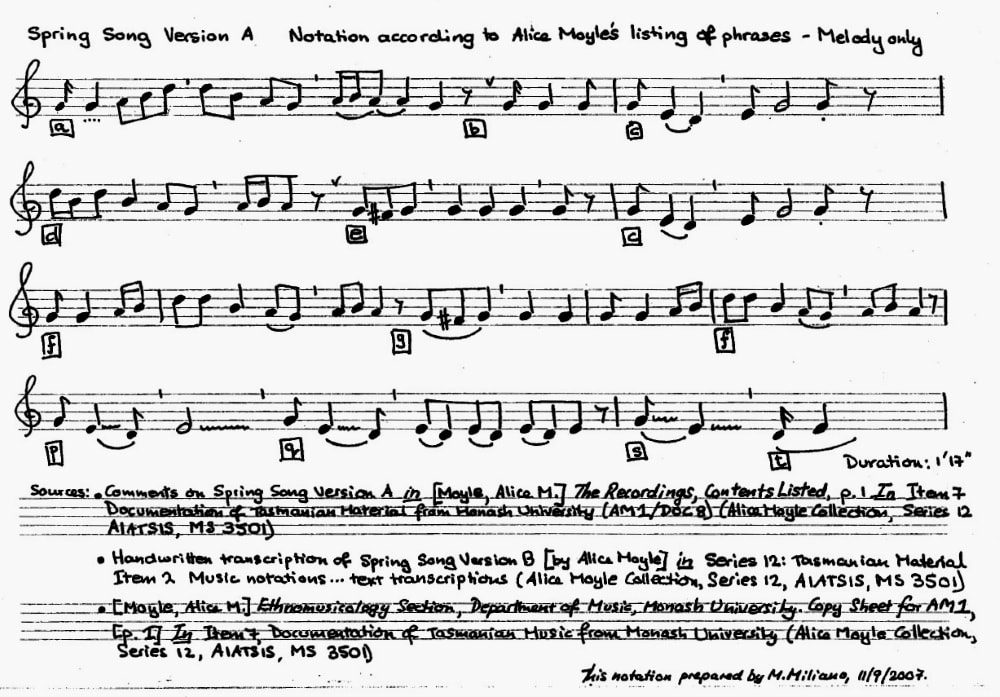

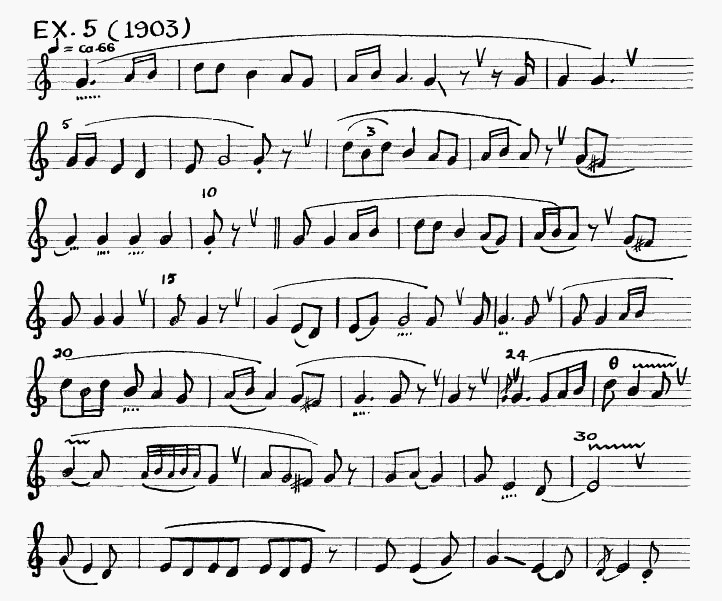

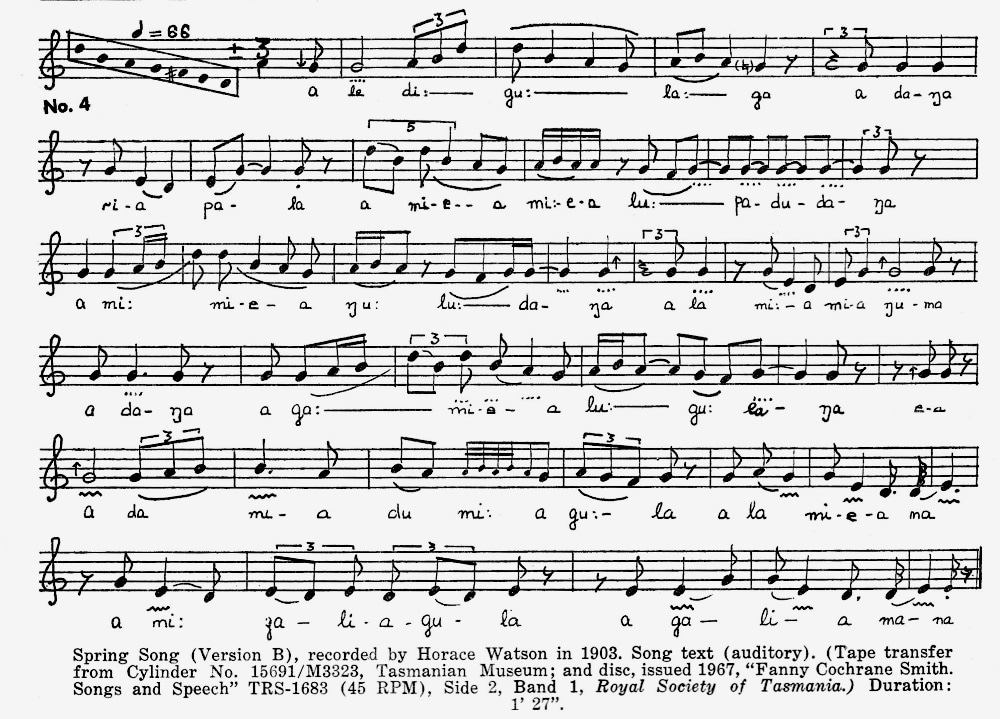

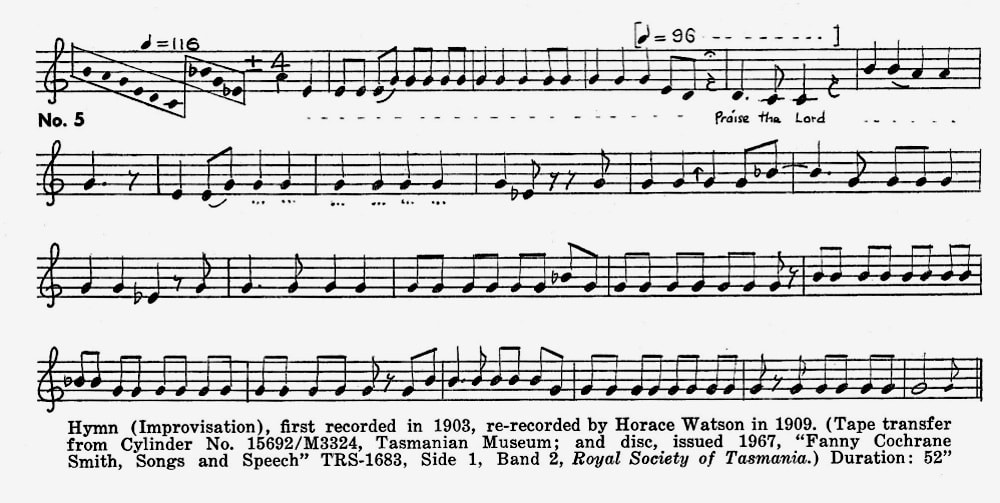

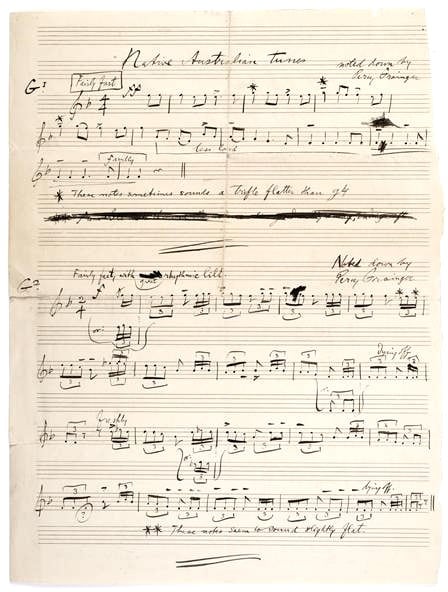

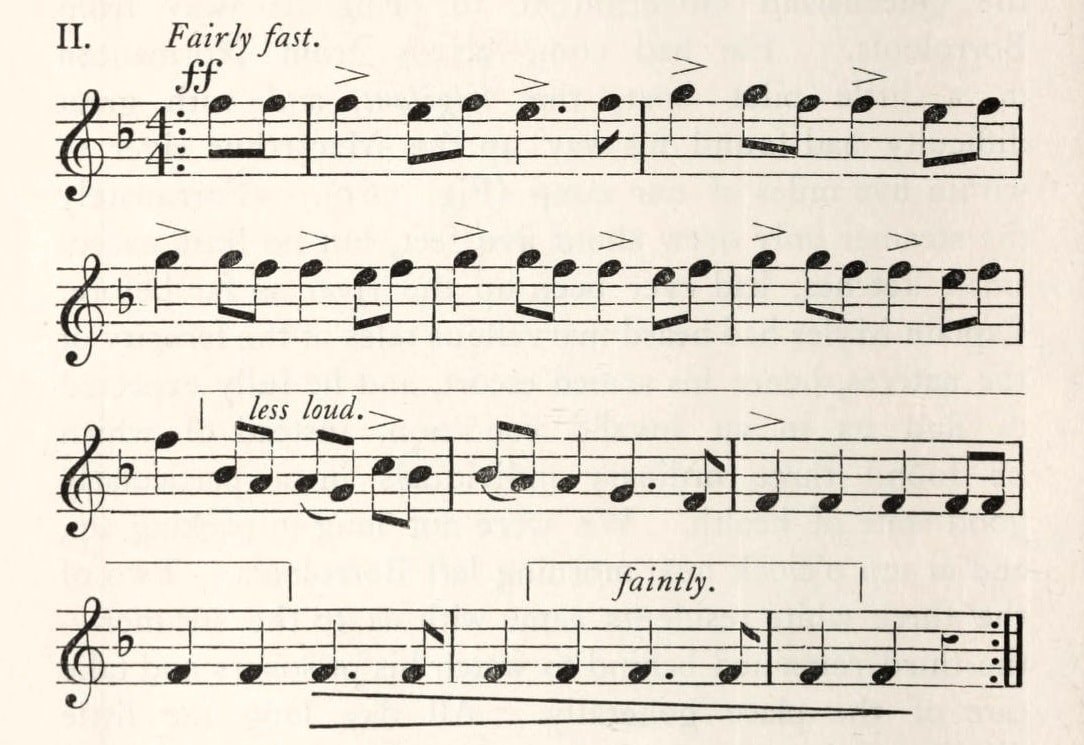

32 3 songs (Tasmanian), 1899 & 1903, Hobart area TAS, recordings 1899 & 1903

33 7 songs (Arrernte), 1901, Central Australia SA NT, recordings 1901

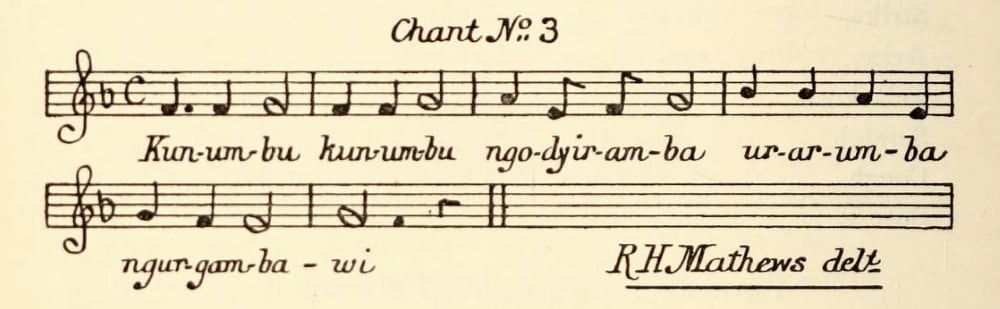

34 6 songs (Dhurga), c.1900, South coast NSW, Mathews 1902

35 3 songs (Dhurga), c.1900-04, South coast NSW, Mathews 1904

Introduction

This web page represents the first stage of a long-term project to create an open access web log of all surviving colonial era documentation of Australian Indigenous song and dance as a specifically musical resource.

Musically specific documentation of ceremonial and recreational song-making, singing, and dancing from the period can be sorted into four cascading categories:

[1] pictorial depictions;

[2] written verbal descriptions;

[3] verbal transcriptions of song texts; and

[4] written musical transcriptions and, at the very end of the colonial era, mechanical recordings.

While category 4 data is the principal focus of this first page, many of the actual documents also record song texts [3], and give further details of performance, meaning, and context described verbally [2] and pictorially [1].

Other complementary pages will be created, in due course, to log documents that lack category [4] data, but are sources for categories [1], [2] and [3].

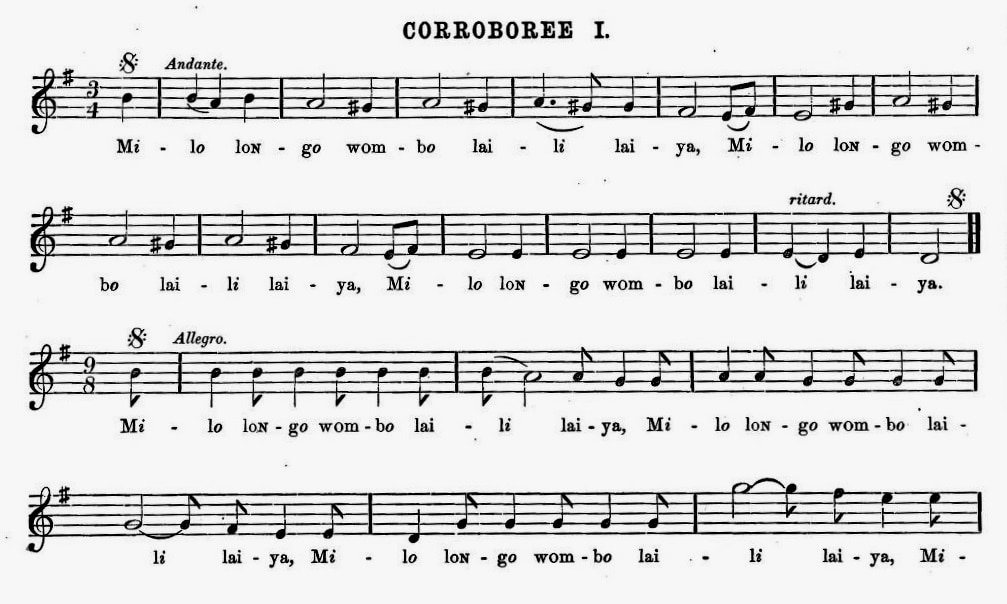

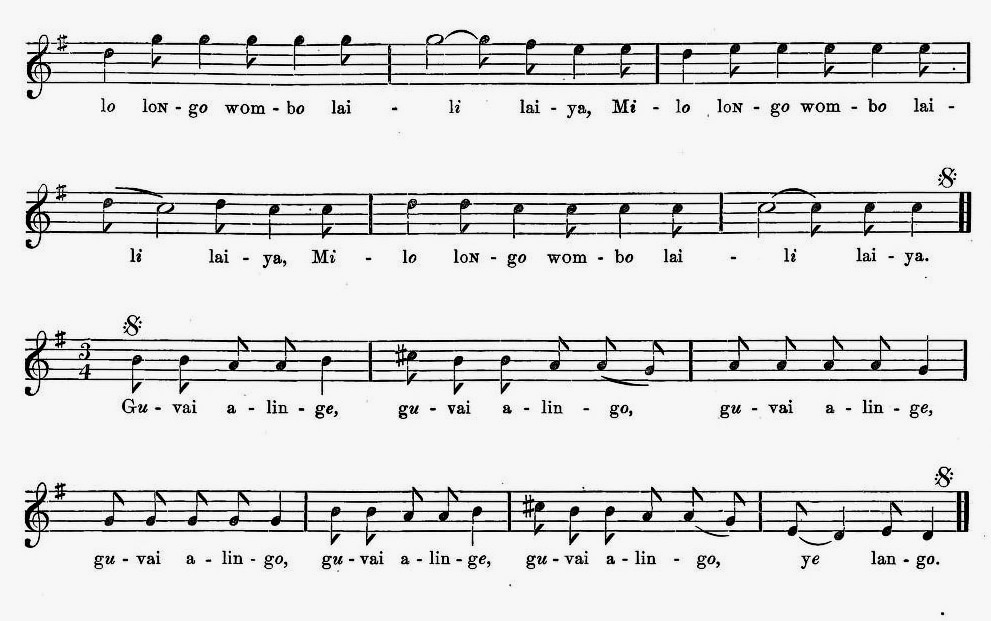

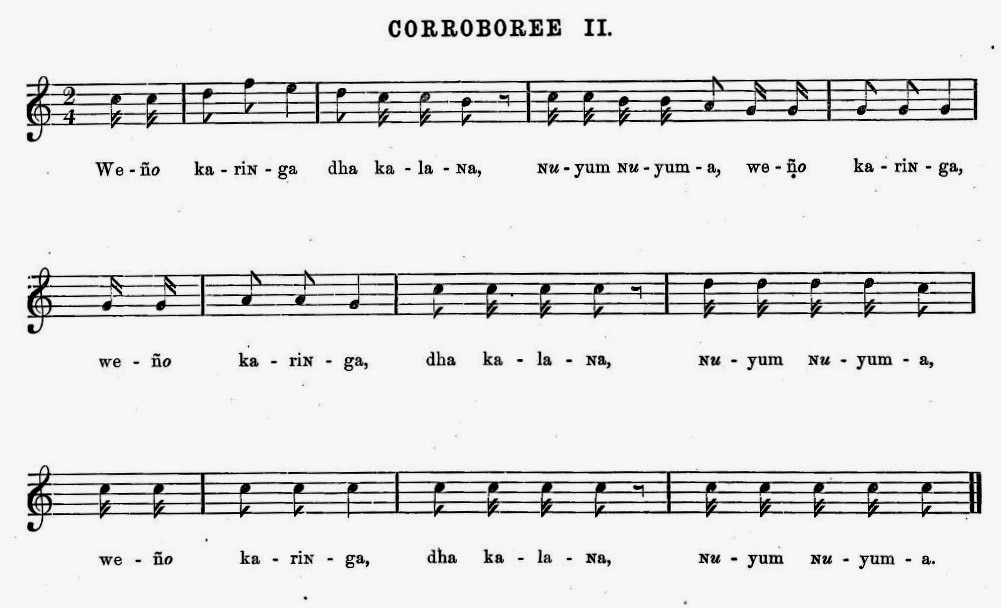

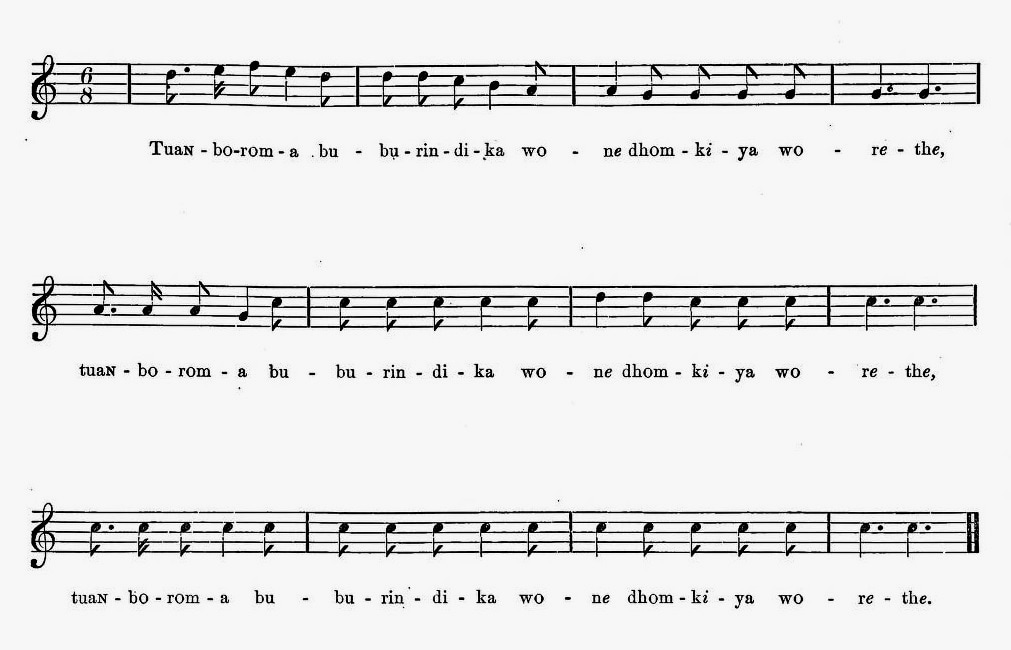

Simply then, this first checklist covers all Australian Indigenous songs documented during the colonial era for which music survives. Until 1898, all the musical records listed here take the form of manual musical transcriptions into Western notation, from live performances or the observer's memories of live performances, with or without accompanying texts, that survive in printed or occasionally manuscript forms (we also list one lost transcription). Some of the musical transcriptions listed were published after 1901 (in one instance, as late as 1937); but we can be fairly certain that they were all based on performances that took place before 1901. Beginning in 1898, we also list three sets of mechanical recordings of songs, the latest of which were taken from live performances in 1901 and 1903, thus extending slightly across the divide (1 January 1901) between the colonial and federated eras.

There are just over 110 items (songs) in the checklist. Around 90 (approximately 80 per cent) include transcriptions of the words of the song, and the majority of these have as well some kind of gloss. These items are dealt with below in 35 entries, or song sets, presented in chronological order. Each set if indicated by a number (1-35), in large red font and boldfaced. Above it, also in red, is the known or estimated likely (best-guess) date of the performance/recording of each song set. Each entry is built around the source or sources that provides the relevant data (minimally, a form of musical notation or a sound recording).

The individual songs within each entry are given a sub-number of the entry number (e.g. 1.1, or 35.3). In one case (the 1898 Torres Strait material in entry 30) the entry includes a number of distinct subsidiary song-sets (e.g. 30.1.1-4 = 4 Keber songs, 30.2.1-9 = 9 Keber songs), so the songs themselves are distinguished with two sub-numbers (e.g. 30.1.1), the first of which indicates the subsidiary set, the second the individual song.

Linguistic data (notes by J. W.)

Under each individual song heading is a block of text in red, which summaries and tabulates linguistic data for each song. These blocks consist of up to four headings, e.g. for the first song:

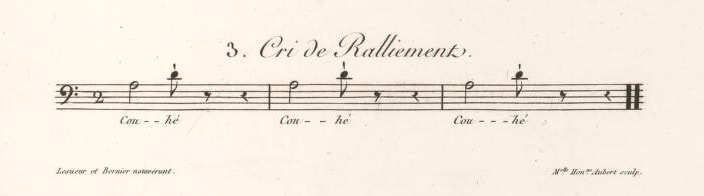

1 "3. Cri de ralliement"

text: Cow-ee [Hunter]; Cou-hé cou-hé cou-hé

gloss: "Come here" (and see Commentary below)

analytics: Sydney area PN (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

On the first line, there is an identifying number, after which each song is identified by a title, either the one provided by the original author or transcriber; or, where none is given, an appropriate word or phrase from the author's or transcriber's text or name; or else another description is supplied editorially. So, for example, the song identification line for one of the songs from south-western Western Australia published in 1892 reads thus: "28.3 id: Calvert 3 (corroborie)".

Where "text" and/or "gloss" for a song occur in the source, these are transcribed after the song identification line.

The "analytics" line consists of three components: first, the name of the place or district in which the evidence suggests the song was recorded; second the "music region" that the place or district pertains to (based on Alice Moyle's 1966 map of Australian music regions, see Moyle 1966, xv-xvii and map 3; also Moyle 1967, 35-43); third, the language, language group, and language family.

To Moyle's seven music regions (ECA, CA, NWCA, NW, BMI, NE and YCA) we have added two: TAS and TSI (see list of abbreviations, below). Of the nine resulting regions, four (NWCA, NW, NE and BMI), all in the far north of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, are not represented in the data available for this period - at least, not with any certainty. (The song identified as "7. Air australien des sauvages de la terre d'Arnheim" was purportedly collected in Arnhem Land, but without any further specification of the locality, so it could conceivably pertain to NW or NE.). For further discussion of Australian music regions, see the introduction to Wafer and Turpin 2017.

Our presentation of the linguistic data proceeds from the general to the specific (language sub-family/ language group/ language) and is hypothetical in most cases, based on the linguistic affiliations of the region in which the recording was made. (We have included these data even when the musical annotation is not accompanied by any text.) Note well that, in some cases, the language of the region is not necessarily the language of the song, which may have originated in a distant location. Where there is an apparent discrepancy, this is noted in the Commentary.

Only one Australian language family, Pama-Nyungan, is represented in the data, since there is no relevant material for the regions in the far north where the non-Pama-Nyungan languages are spoken. (There is, however, one entry, 30 Torres Strait Island songs, that includes several song-sets from the Eastern Torres Strait, where the language is said to belong to the Papuan family.) We have adopted the four-fold division of Pama-Nyungan proposed by Bowern and Atkinson 2012: "South-eastern", "Northern", "Central", and "Western"; so the language sub-family given for most entries is an abbreviated form of one of these ("South-eastern PN" etc.). Our language group names are also based largely on Bowern and Atkinson, and our language names on the most representative current usage. To give an example: the linguistic analytics for the first song read thus: Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

Conventions and abbreviations

The abbreviated terms used by Moyle for her music regions (1966) can be interpreted as follows:

ECA East Central Arid

CA Central Arid

NWCA North-west Central Arid

NW North-west

BMI Bathurst and Melville Islands

NE North-east

YCA Cape York Central Arid

Note that we have added two:

TAS Tasmania

TSI Torres Strait Islands

A edited print-format summary of the text of this page, as of 2017, appears in a printed version as:

Skinner and Wafer 2017

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 360-404

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/228833695

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

See also Skinner's and Wafer's commentaries:

Skinner 2017

Graeme Skinner, "Recovering musical data from colonial era transcriptions of Indigenous songs: some practical considerations", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 336-59

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/228833695

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/25/16_skinner.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Wafer 2017

Jim Wafer, "Ghost-writing for Wulatji: incubation and re-dreaming as song revitalisation practices", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 187-244

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/228833695

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/18/9_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

References:

Alice M. Moyle, Handlist of field collections of recorded music in Australia and Torres Strait (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10724303

Alice M. Moyle, Songs from the Northern Territory: companion booklet (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1967)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/45681402

Claire Bowern and Quentin Atkinson, "Computational phylogenetics and the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan", Language 88 (2012), 817-845

http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ling_faculty/1 (DIGITISED)

Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin, "Introduction", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 1-4

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/228833695

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/9/0_introduction.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

By 1789

1 1 song call

Dharug, Sydney area, NSW

First reported by John Hunter (1737-1821), central coast NSW, 5 July 1789

First musical notation, made by Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846) and Pierre François Bernier (1779-1803), members of the Baudin expedition, from unidentified performers, probably in the Sydney area, sometime between late June and November 1802; first published Paris, 1824

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#001 (shareable link to this entry)

Couhé (cooee; coo-ee; coo-ey)

1 "3. Cri de ralliement"

text: Cow-ee [Hunter]; Cou-hé cou-hé cou-hé

gloss: "Come here" (and see Commentary below)

analytics: Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

Sources and documentation:

John Hunter, An historical journal at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island . . . from the first sailing of the Sirius in 1787, to the return of that ship's company to England in 1792 (London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1793), 149, 407

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/1bGMdJXY/BGWypKD2M8bRZ (DIGITISED - IMAGE 179)

[149] [4 July 1789] . . . we called to them in their own manner, by frequently repeating the word Co-wee, which signifies, come here . . .

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/1bGMdJXY/x5eMA2Q5m3LEW (DIGITISED - IMAGE 545)

. . . [407] I shall now add a vocabulary of the language, which I procured from Mr. Collins and Governor Phillip;

both of whom had been very assiduous in procuring words to compose it; and as all the doubtful words are here rejected, it may be depended upon to be correct.*

[* This Vocabulary was much enlarged by Captain Hunter.] . . .

[408] . . . Cow-ee, To come . . .

John Hunter, An historical journal at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island . . . [abridged edition] (London: John Stockdale, [1793]), 120 [word only]

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=t0tfAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA120 (DIGITISED)

[149] [4 July 1789] . . . we called to them in their own manner, by frequently repeating the word Co-wee, which signifies, come here . . .

Charles Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, Voyage de découvertes aux terres Australes; historique, atlas par MM. Lesueur et Petit, seconde édition (Paris: Chez Arthus Bertrand, 1824), plate 32, page 52, no. 3 [word and musical transcription]

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=aXVdAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA32 (DIGITISED)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/20117482

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-32726430 [plate only] (DIGITISED)

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/98350 [plate only] (DIGITISED)

Musique des sauvages de la Nouvelle-Galles du Sud divers airs notés [table of contents]

. . . 3. Cri de Ralliement.

Cou-hé cou-hé cou-hé

NOUVELLE-HOLLANDE: N[ouv]elle Galles du Sud.

MUSIQUE DES NATURELS.

Lesueur at Bernier notaverunt. / M'elle Hon'ne Aubert sculp[sit]. / J. Milbert direx[it].

For nos. 1 and 2 on the same plate, see 3.1 and 3.2 below

Other musical editions (before 1901):

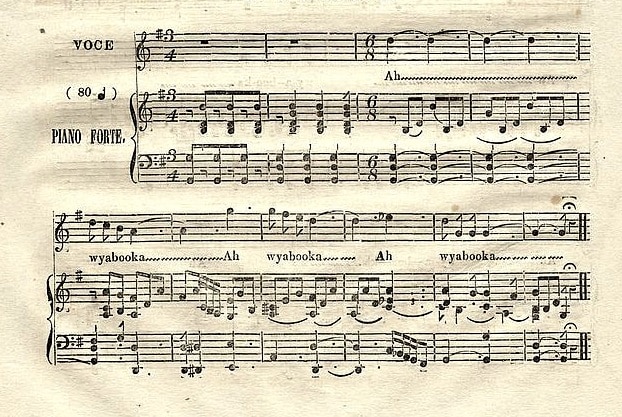

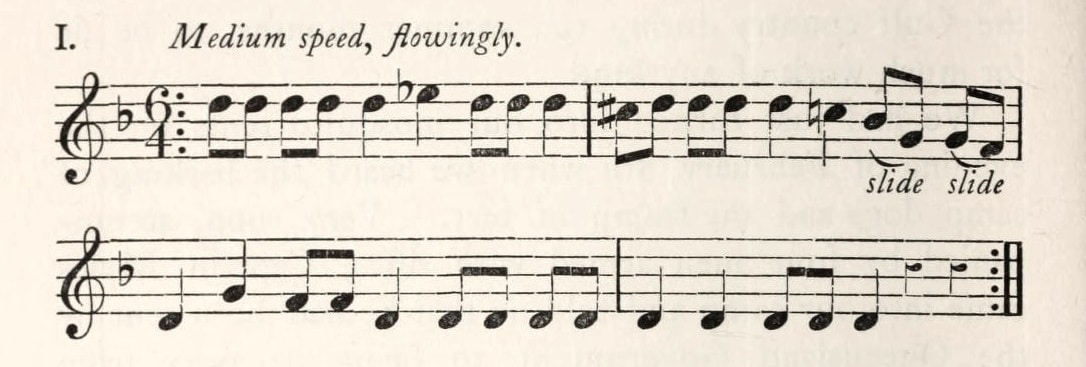

"The Koo-ee", in Isaac Nathan, The southern Euphrosyne, and Australian miscellany (Sydney: I. Nathan, [1848-49]), 102-104 (commentary and music)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/6685469

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-166023361/view#page/n111/mode/1up (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ziwieom4lBQC&pg=PA102 (DIGITISED)

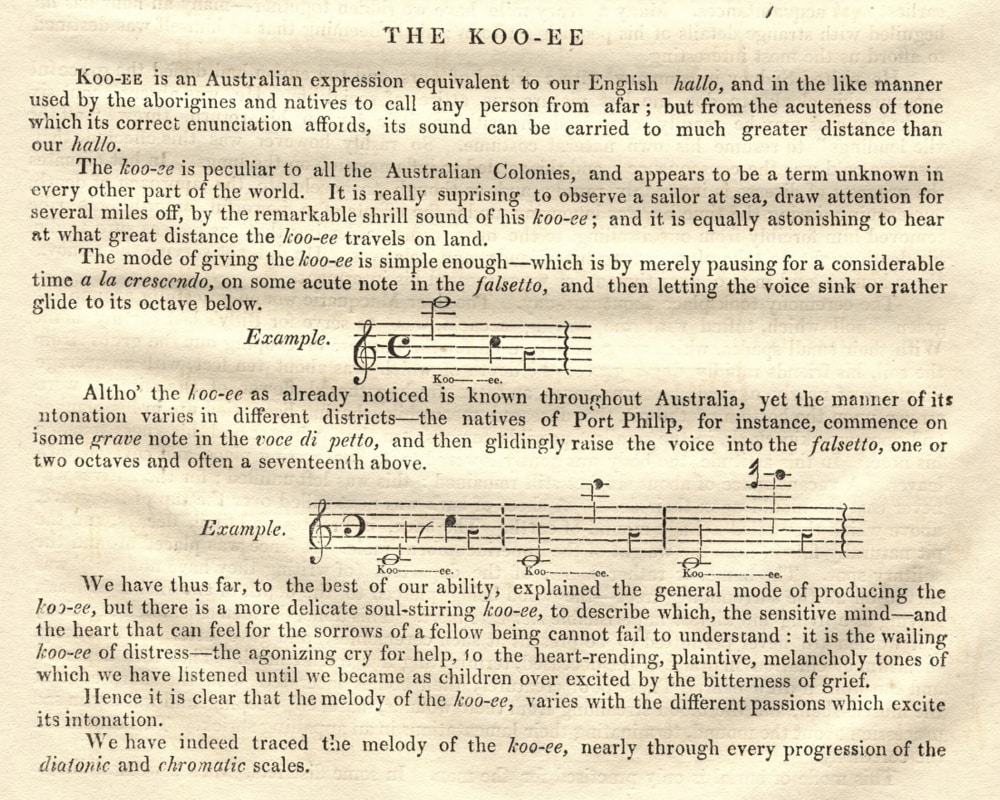

KOO-EE is an Australian expression equivalent to our English hallo, and in the like manner used by the aborigines and natives to call any person from afar; but from the acuteness of tone which its correct enunciation affords, its sound can be carried to much greater distance than our hallo.

TThe koo-ee is peculiar to all the Australian Colonies, and appears to be a term unknown in every other part of the world. It is really surprising to observe a sailor at sea, draw attention for several miles off, by the remarkable shrill sound of his koo-ee; and it is equally astonishing to hear at what great distance the koo-ee travels on land.

The mode of giving the koo-ee is simple enough - which is by merely pausing for a considerable time a la crescendo, on some acute note in the falsetto, and then letting the voice sink or rather glide to its ocatve below.

[EXAMPLE]

Altho' the koo-ee as already noticed is known throughout Australia, yet the manner of its intonation varies in different districts - the natives of Port Philip, for instance, commence on on some grave note in the voce di petto, and then glidingly raise the voice into the falsetto, one or two octaves and often a seventeenth above. [EXAMPLE]

[EXAMPLE]

We have thus far, to the best of our ability, explained the general mode of producing the koo-ee, but there is a more delicate soul-stirring koo-ee, to describe which, the sensitive mind - and the heart that can feel for the sorrows of a fellow being cannot fail to understand: it is the wailing koo-ee of distress - the agonizing cry for help, to the heart-rending, plaintive, melancholy tones of which we have listened until we became as children over excited by the bitterness of grief.

Hence it is clear that the melody of the koo-ee, varies with the different passions which excite its intonation.

We have indeed traced the melody of the koo-ee, nearly through every progression of the diatonic and chromatic scales.

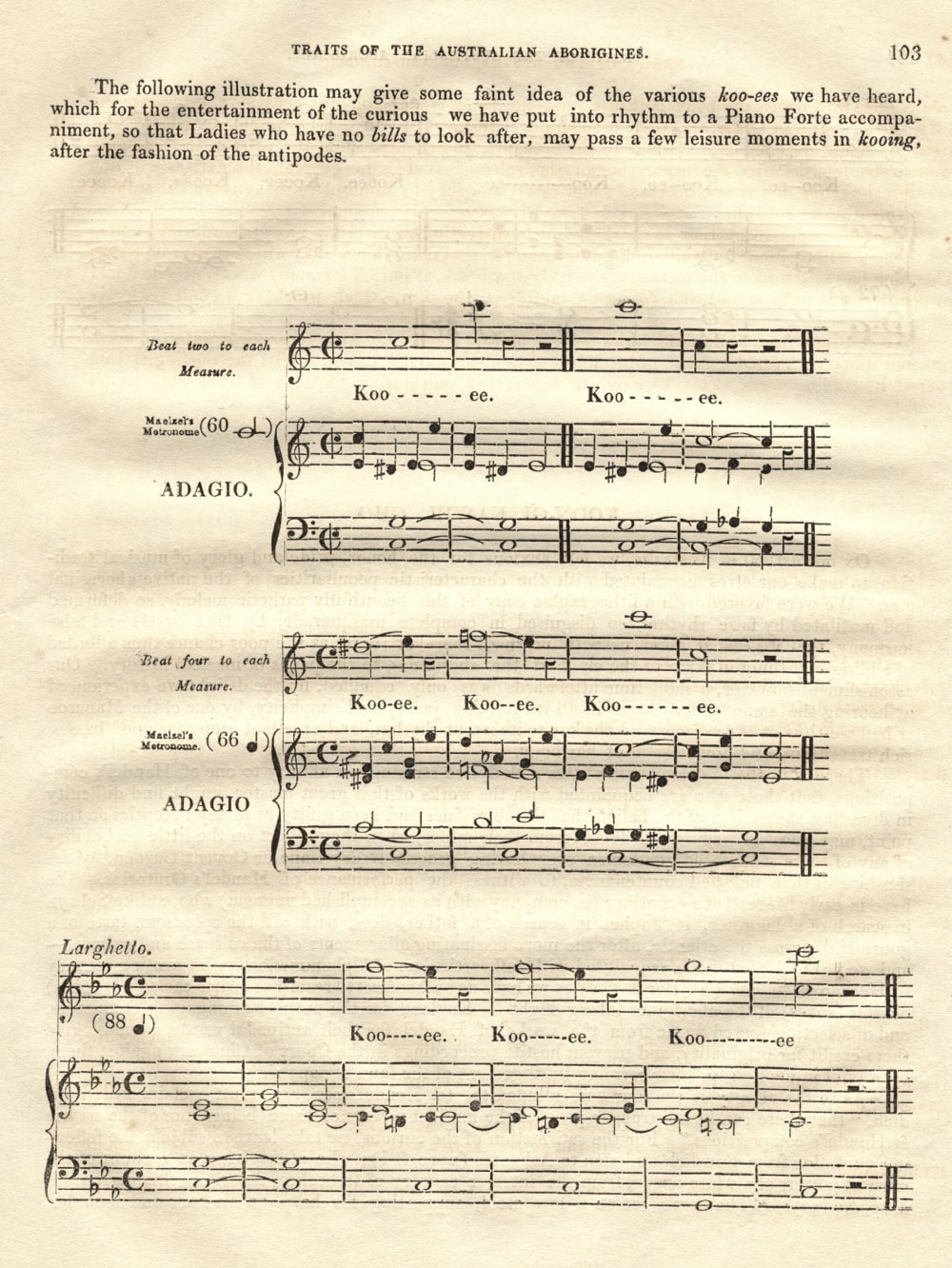

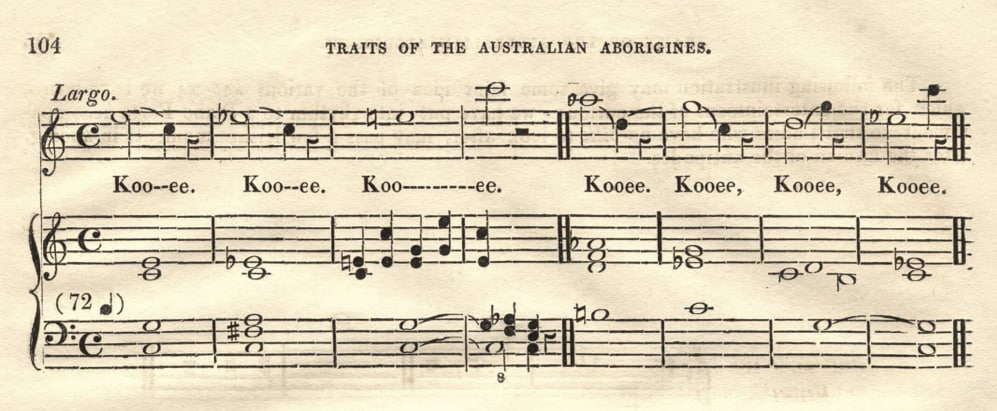

[103] The following illustration may give some faint idea of the various koo-ees we have heard, which for the entertainment of the curious we have put into rhythm to a Piano Forte accompaniment, so that Ladies who have no bills to look after, may pass a few leisure moments in kooing, after the fashion of the antipodes.

[EXAMPLES]

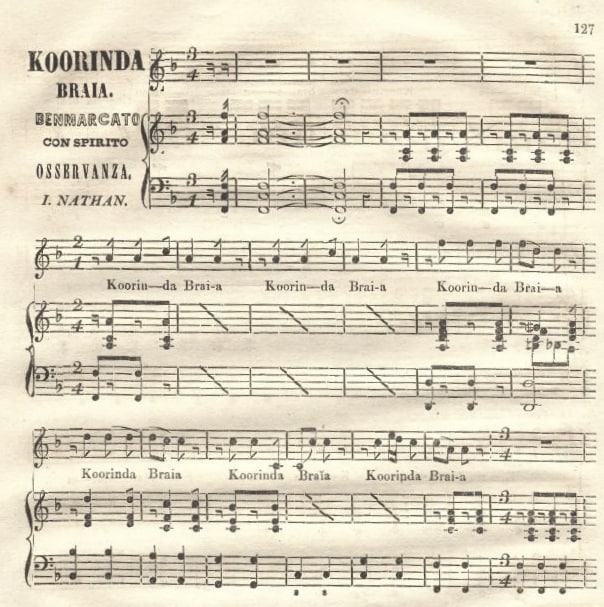

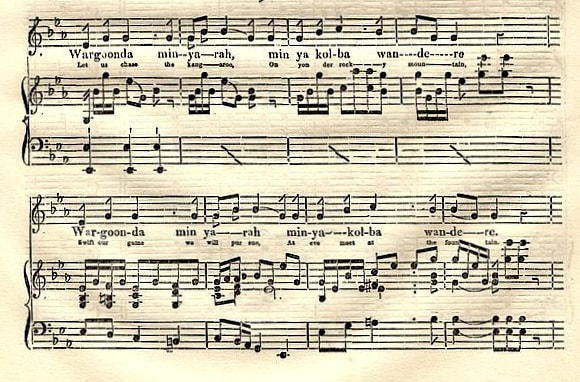

"Koorinda Braia" [second edition, with koo-ees newly added], in Isaac Nathan, The southern Euphrosyne . . ., 129-132

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-166023361/view#page/n138/mode/1up (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ziwieom4lBQC&pg=PA129 (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: Isaac Nathan (composer, arranger, author); for full details, see main entry on Koorinda Braia

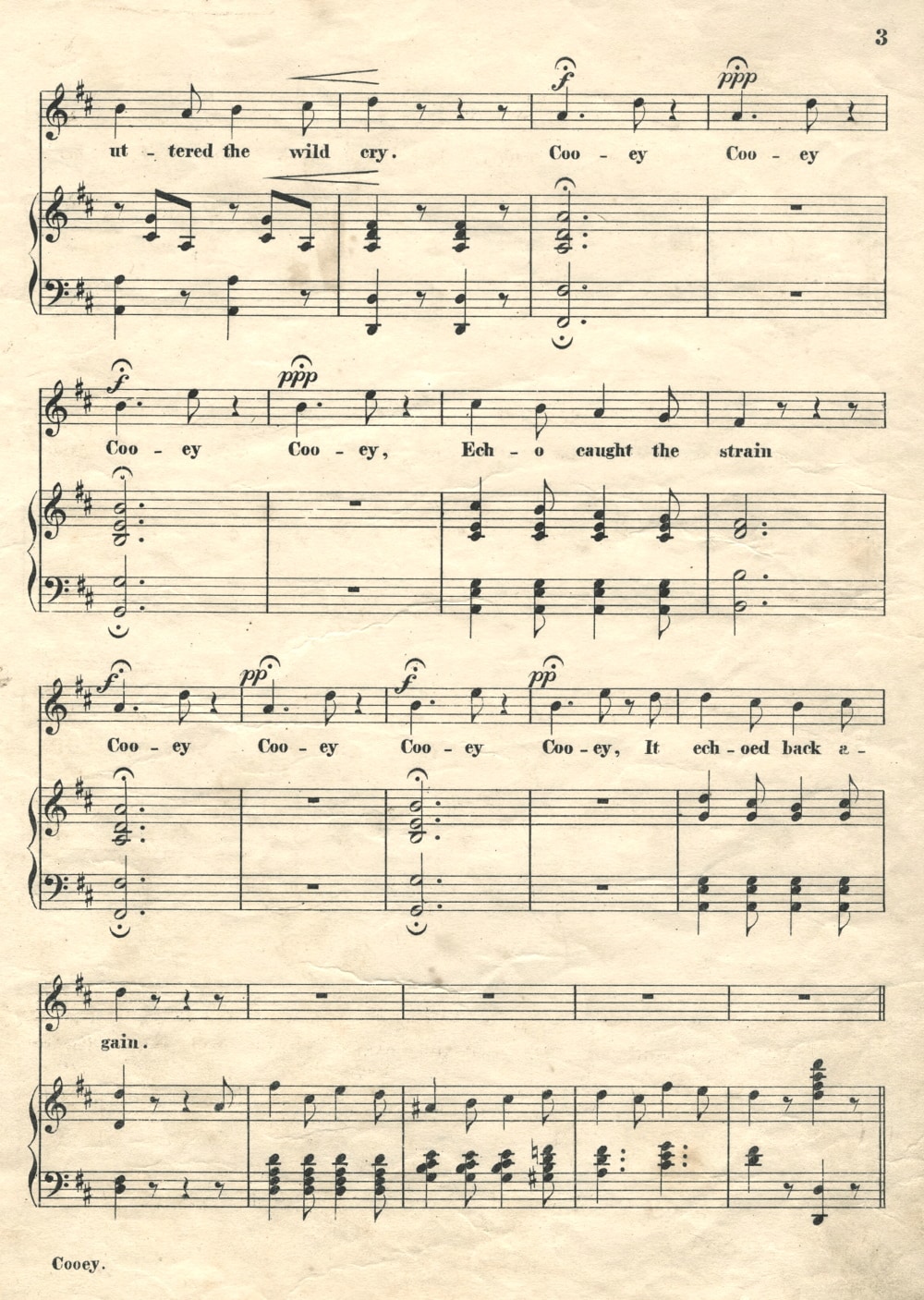

Cooey! an Australian song, words by an Australian lady, music by Spagnoletti R.A. (Sydney: John Davis, [1860])

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/13522435

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-164961728 (DIGITISED)

Video recording of live performance by Elizabeth Connell (1946-2012), London, November 2010

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TM5FiSfDrEE (STREAMED VIDEO)

ASSOCIATIONS: Ernesto Spagnoletti (composer, arranger); "an Australian lady" = Jane Davies (lyricist)

Select bibliography (before 1901):

Peter Cunningham, Two years in New South Wales: comprising sketches of the actual state of society in that colony . . . second edition, revised and enlarged (London: Henry Colburn, 1827), volume 2, 23

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=lfxEAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA23 (DIGITISED)

. . . In calling to each other at a distance, they make use of the word Coo-ee as we do the word Hollo, prolonging the sound of the coo, and closing that of the ee with a shrill jerk. This mode of call is found to be so infinitely preferable to the Hollo, both on account of its easier pronunciation and the great distance at which it can be heard, as to have become of general use throughout the colony; and a new comer, in desiring an individual to call another back, soon learns to say "Coo-ee to him," instead of "Hollo to him" . . .

Louis de Freycinet, Voyage autour du monde entrepris par ordre du Roi . . . exécuté sur les corvettes de S. M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820, historique, tome deuxième - deuxième partie (Paris: Chez Pillet Ainé, 1839), 744, 774-775

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA744 (DIGITISED)

. . . Cri pour se reconnaître. - Leur cri particulier pour se reconnoître de loin, est kouhi, ou encore kouh [Voyez plus bas l'article Musique], auquel répondent de la même façon ceux qui ont entendu le premier appel. A ce signal, qui n'est que d'avertissement, succède, s'il s'agit de l'arrivée d'un étranger, la phrase interrogative: qui êtes-vous! question à laquelle celui-ci doit s'empresser de satisfaire. Le nom du visiteur répété alors de bouche en bouche, se répand bientôt dans toute-la peuplade; et la réception qu'on fait ensuite au nouveau venu, est en raison de l'intérêt qu'il inspire . . .

NOTE: There is at least one extant copy of this edition (see New York Public Library exemplar) that incorrectly gives the year of publication as 1829; correctly 1839

Charles Griffith, The present state and prospects of the Port Phillip district of New South Wales (Dublin: William Curry, 1845), 65

https://archive.org/stream/presentstateand00grifgoog#page/n76/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

[FOOTNOTE] The cooey is a call in universal use amongst the settlers, and has been borrowed from the natives. The performer dwells for about half a minute [sic] upon one note, and then raises his voice to the octave. It can be heard at a great distance.

Edward E. Morris, Austral English: a dictionary of Australasian words, phrases and usages (London: Macmillan and Co., 1898), 95-96

https://archive.org/stream/australenglishdi00morruoft#page/95/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

Select bibliography (since 1901):

Roger Covell, Australia's music: themes of a new society (Melbourne: Sun Books, 1967), 69, 325

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/21095423

See also second edition, 2016

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/21095423/version/227555462

Nicole Saintilan, "Music - if so it may be called": perception and response in the documentation of Aboriginal music in nineteenth century Australia (M.Mus thesis, University of New South Wales, 1993), 11-16

http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/50383 (DIGITISED)

Pru Neidorf, "Coo-ee", in John Whiteoak and Aline Scott-Maxwell (eds), Currency companion to music and dance in Australia (Sydney: Currency House, 2003), 188

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/22233842

Graeme Skinner, Toward a general history of Australian musical composition: first national music, 1788-c.1860 (Ph.D thesis, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, 2011), 62

http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7264 (DIGITISED)

Keith Vincent Smith, "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales", eBLJ (Electronic British Library Journal) (2011, article 14), (1-7), 5

http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle142011.pdf (DIGITISED)

Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby, "Cross-cultural inquiry in 1802: musical performance on the Baudin expedition to Australia", in Kate Darian-Smith and Penelope Edmonds (eds), Conciliation on colonial frontiers: conflict, performance, and commemoration in Australia and the Pacific rim (New York and Oxford: Routledge, 2015), (henceforth Fornasiero and West-Sooby 2015), 17-35, esp. 25

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VVehBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA25 (PREVIEW)

Page 25 has image of the handcopy text for the music plate of the Lesueur and Petit atlas of 1824 (Lesueur Collection, Muséum de l'Histoire Naturells, Le Harve, nos. 16057R , 16059-1)

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 365-67

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Commentary:

James Backhouse Walker (1890, 131) surmised that "a sound like to trumpet or small gong" heard by Abel Tasman's party in Tasmania in 1642 was 'probably a cooey'". In 1789, John Hunter reported: "We called to them in their own manner, by frequently repeating the word Cow-ee, which signifies, come here" (Hunter 1793, 120). Based on a comparison of various historical records, Jakelin Troy (1994, 79) reconstructed the phonology as /gawi/ and derives the expression from the verb gama, "to call", suffixed with (a contraction of) the third person marker -wawi (1994, 29). Dixon, Ramson and Thomas (1990, 208), on the other hand, reconstructed the phonology as /'kui/ or /ku'i/ and represented it orthographically as guuu-wi. Both analyses adopt Hunter's gloss ("come here"), although a number of the sources suggest that the expression was more a generic signal indicating one's presence and location and soliciting the same kind of response from others. Freycinet (1839, 744), for example, says that "ce signal . . . n'est que d'avertissement" (see also e. g. Cunningham 1827 v.2, 23).

References:

James Backhouse Walker, "The discovery of Van Diemen's Land in 1642: notes on the localities mentioned in Tasman's journal of the voyage", Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania (1890), 274

http://eprints.utas.edu.au/16735 (DIGITISED)

. . . On [2 December 1642], early in the morning, the boat was sent to explore, and entered a bay a good 4 miles to the north-west (Blackman's Bay). The boat was absent all day, and returned in the evening with a quantity of green-stuff which was found fit to cook for vegetables. The crew reported that they had rowed some miles after passing through the entrance to the bay (now known as the Narrows). They had heard human voices, and a sound like a trumpet or small gong (probably a cooey), but had seen no one . . .

James Backhouse Walker, The discovery of Van Diemen's Land in 1642: notes on the localities mentioned in Tasman's journal of the voyage (Hobart: William Thomas Strutt, Government Printer, 1891), 6

Offprint of Walker 1890 above

http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/82203 (DIGITISED)

James Backhouse Walker, Early Tasmania; papers read before the Royal Society of Tasmania during the years 1888 to 1899 ([Hobart] Tasmania: John Vail, government printer, 1902), 131

Feprint of Walker 1890 above

https://archive.org/stream/earlytasmaniapap00walk#page/131/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

R. M. W. Dixon, W. S. Ramson and Mandy Thomas, Australian Aboriginal words in English: their origin and meaning (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1990)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/6268730

Jakelin Troy, The Sydney language (Canberra: the author, with assistance from the Australian Dictionaries Project and AIATSIS, 1994)

http://www.williamdawes.org/docs/troy_sydney_language_publication.pdf (DIGITISED)

c. 1790

2 1 song

Dharug, Sydney area, NSW

Song known to have been sung by Wangal and perhaps also Cadigal people, the words separately transcribed in or around Sydney by William Dawes (c. 1790/91), John Hunter (c. 1790/91), and David Collins (before 1796)

Music and words transcribed by Edward Jones (1752-1824), from two Wangal men, Woollarawarre Bennelong (c. 1764-1813) and Yemmerrawanne (c. 1775-1794), in London, England, mid 1793; musical transcription first published London, 1811

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#002 (shareable link to this entry)

Barrabu-la

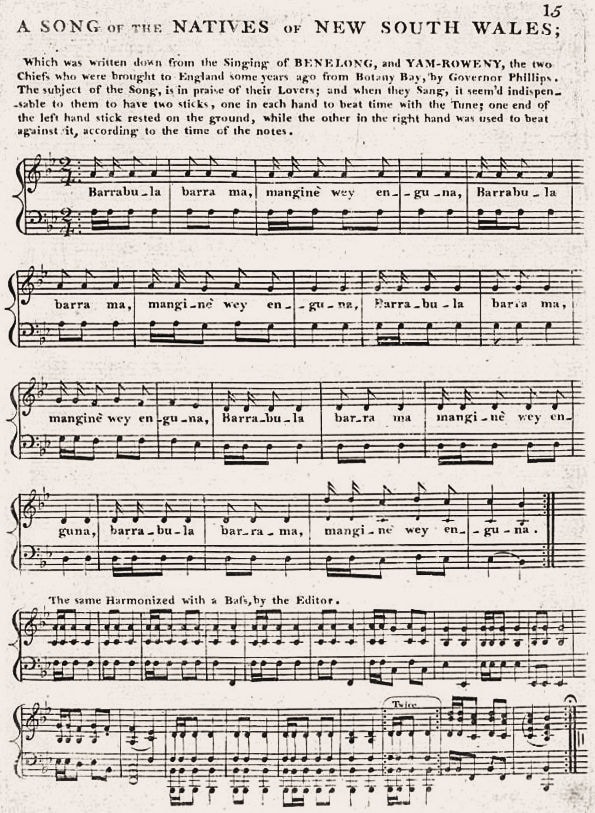

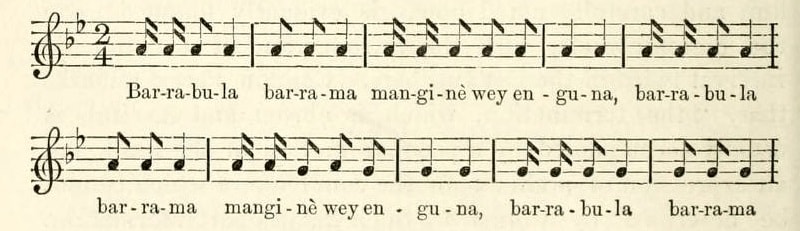

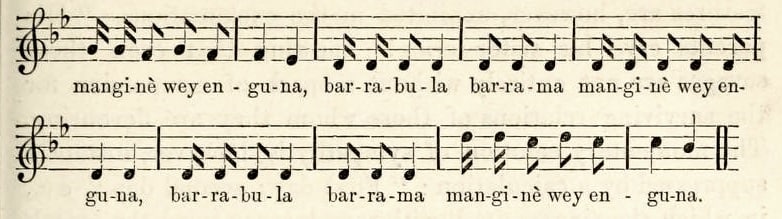

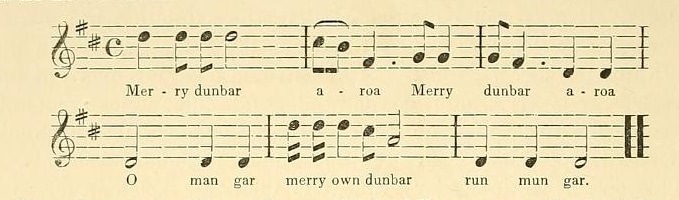

2 "A SONG OF THE NATIVES OF NEW SOUTH WALES; Which was written down from the Singing of BENELONG, and YAM-ROWENY, the two Chiefs, who were brought to England some years ago from Botany Bay, by Governor Phillips [sic] (Jones 1811, 15).

text: Barrabu-la barra ma, manginè wey en-gu-na . . . [repeats] (Jones 1811, 15)

gloss: "The words are the names of deceased persons" (Collins 1798, 616); "The subject of the Song, is in praise of their Lovers" (Jones 1811, 15)

analytics: Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

Sources (words only):

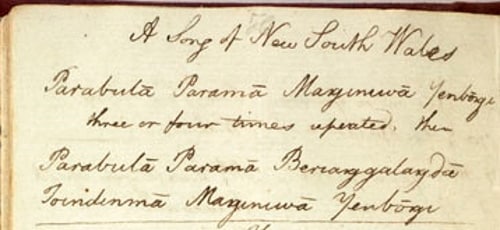

Notebooks of William Dawes, Sydney, NSW, 1790-91; University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, MS 41645; Book B, 31: "A Song of New South Wales", perhaps taken from the singing of his regular source, the young Cadigal woman, Patyegarang:

http://www.williamdawes.org/ms/msview.php?image-id=book-b-page-31 (DIGITISED)

See also facsimile edition with introduction and commentary, David Nathan, Susannah Rayner and Stuart Brown (eds), William Dawes' notebooks on the Aboriginal language of Sydney, 1790-1791 (London: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2009), especially 41

http://www.dnathan.com/eprints/dnathan_etal_2009_dawes.pdf (DIGITISED

A Song of New South Wales

Parabulā Paramā Manginiwā Yenbōngi

three or four times repeated, then

Parabulā Paramā Berianggalangdā

Toindinmā Manginiwā Yenbōngi

ASSOCIATIONS: William Dawes (reporter, recorder); Patyegarang (singer)

John Hunter, An historical journal of the transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island . . . from the first sailing of the Sirius in 1787 to the return of that ship's company to England in 1792 (London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1793), 413-14

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/1bGMdJXY/aZKKVykrzKbJG (DIGITISED)

[413] [April 1790] . . . He [Bennelong] calls Governor Phillip, Beanga (father); and names himself Dooroow (son): the judge and commissary [David Collins] he calls Babunna (brother). He sings a great deal, and with much variety: the following are some words which were caught -

"E eye at wangewah-wandeliah chiango wandego mangenny wakey angoul barre boa lah barrema" . . .

[414] The natives sing an hymn or song of joy, from day-break until sunrise . . .

NOTE: For "E eye at wangewah-wandeliah chiango wandego" see also Fishing song (5.2) below

David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales: with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country . . . (London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, 1798), 616

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eRZcAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA616 (DIGITISED)

. . . Words of a Song:

Mang-en-ny-wau-yen-go-nah, bar-ri-boo-lah, bar-re-mah.

This they begin at the top of their voices, and continue

as long as they can in one breath, sinking to the lowest note, and then rising again to the highest. The words are the names of deceased persons . . .

Source (words and music):

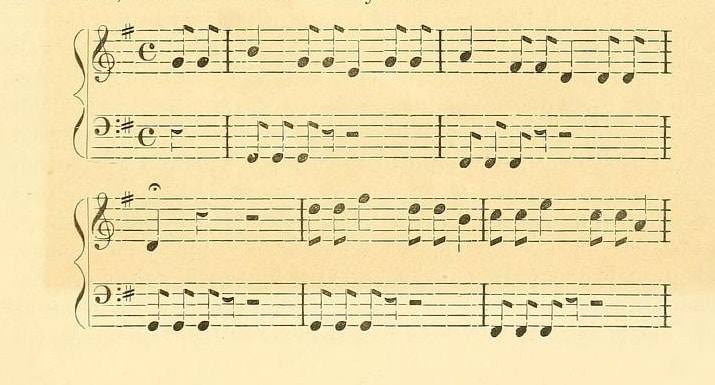

Edward Jones, Musical curiosities; or, a selection of the most characteristic national songs, and airs; many of which were never before published: consisting of Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Danish, Lapland, Malabar, New South Wales, French, Italian, Swiss, and particularly some English and Scotch national melodies, to which are added, variations for the harp, or the piano-forte, and most humbly inscribed, by permission, to her royal highness the princess Charlotte of Wales . . . (London: Printed for the author, 1811), 15 (music and words)

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/497313581

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/16450109

Facsimile in Keith Vincent Smith, "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales", eBLJ (Electronic British Library Journal) (2011, article 14), (1-7), 1 (exemplar London, British Library, R.M.13.f.5)

http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle142011.pdf (DIGITISED)

Facsimile in Smith 2012, [n.p.] (exemplar London, British Library, R.M.13.f.5)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=E0PIa25UCMAC&pg=PT96 (PREVIEW)

A SONG OF THE NATIVES OF NEW SOUTH WALES; Which was written down from the Singing of BENELONG, and YAM-ROWENY, the two Chiefs, who were brought to England some years ago from Botany Bay, by Governor Phillips [sic]. The subject of the Song, is in praise of their Lovers; and when they Sang, it seem'd indispensible to them to have two sticks, one in each hand to beat time with the Tune; one end of the left stick rested on the ground, while the other in the right hand was used to beat against it, according to the time of the notes.

Facsimile below, of source song only (exemplar London, British Library, R.M.13.f.5)

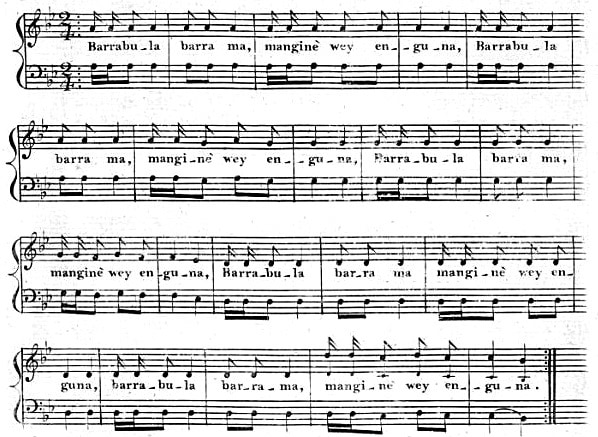

Barrabula barra ma, manginè wey enguna,

Barrabula barra ma, manginè wey enguna,

Barrabula barra ma, manginè wey enguna,

Barrabula barra ma, manginè wey enguna,

barrabula barra ma, manginè wey enguna.

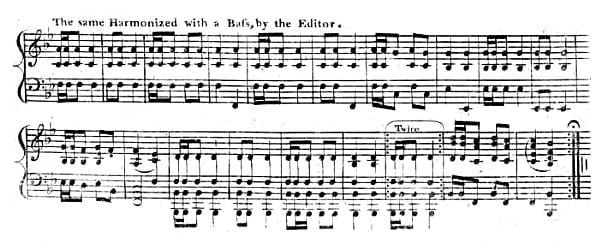

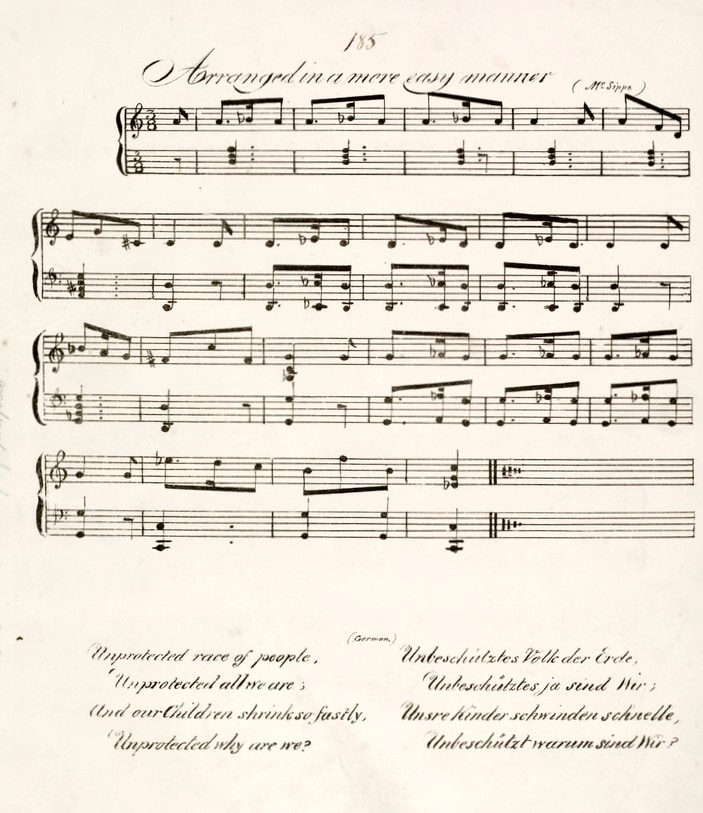

The same Harmonized with a Bass, by the Editor

Facsimile below, of Jones's arrangement ("variation for the harp, or the piano-forte") only (exemplar London, British Library, R.M.13.f.5)

Sound:

Melody and rhythm as transcribed by Edward Jones, 1793 (Jones 1811), synthesised using bass woodwind sounds as approximations for voices, Australharmony 2016; for ease of comparison see images below from Engel 1866, 26-27

medialocal/1793-barrabula-song-mod.wav

Harmonised version (Jones 1811), synthesised for harp, Australharmony 2016

Keith Vincent Smith, "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales", eBLJ (Electronic British Library Journal) (2011, article 14), (1-7), 7

http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle142011.pdf

Page 7 of the pdf has an embedded sound file of Barrabu-la (c.1790), and Harry's Song (c.1820) performed in traditional style by two Indigenous Australian performers, Clarence Slockee and Matthew Doyle, at the opening of the Mari Wari exhibition, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 24 September 2010

Another slightly varied take, by the same artists, of Barrabu-la (streamed ABC Radio)

http://mpegmedia.abc.net.au/rn/podcast/extra/2011/hht_20110403_BennelongYemmerrawanneLivePerformance.mp3 (STREAMED SOUND)

"GUYANAYA BAYUI: OLD PEOPLE, FUTURE", Deepening Histories (Australian National University)

http://deepeninghistories.anu.edu.au/sites/music-day/play.php?UUID=90f02a58-4b8c-4a0d-ab43-ad32211343f1 (STREAMED VIDEO)

Newly imagined performances in contemporary experimental idiom, by Richard Green, Karen Smith, Matt Doyle, Clarence Slockee, with Kevin Hunt, features Barabul-la (c. 1790), Chant (1802), and Harry's Song (c. 1820)

Bibliography and resources:

Carl Engel, An introduction to the study of national music: comprising researches into popular songs, traditions, and customs (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1866), 26-27 (see music images below)

https://archive.org/stream/introductiontost00enge#page/26/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=0k4QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA26 (DIGITISED)

. . . In the following song of the natives of New South Wales we have a succession of diatonic intervals in descending. Edward Jones states that this air "was written down from the singing of Benelong and Yamroweny, the two chiefs who were brought to England, some years ago, from Botany Bay, by Governor Phillips. The subject of their song is in praise of their lovers; and when they sang, it seemed indispensable to them to have two sticks, one in each hand, to beat time with the tune; one end of the left-hand stick rested on the ground, while the other in the right hand was used to beat against it, according to the time of the notes. [Musical Curiosities, by Edward Jones, London, 1811, p. 15.] . . .

Reproduces words and melody only, after Jones 1811

James Bonwick, Daily life and origins of the Tasmanians (London: Samson, Low, Son, and Marston: 1870), 33

https://archive.org/stream/dailylifeandori02bonwgoog#page/n51/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=rQ5zAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA33 (DIGITISED)

. . . The first native song was published by Mr. Edward Jones of London in 1811, in "Musical Curiosities." It was taken from a love-song sung by Bennilong and Yamroweng [sic], on their visit to England in the beginning of this century [sic]. "It shows," says Carl Engel, "a succession of diatonic intervals in descending." It is placed in two flats . . .

Reproduces words and melody, copied from Engel 1866, cites Jones

Richard Wallaschek, Primitive music: an inquiry into the origin and development of music, songs, instruments, dances, and pantomimes of savage races (London; New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893), 41

https://archive.org/stream/primitivemusicin00wall#page/41/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

. . . Bonwick quotes two Australian songs borrowed from B. Field and Edward Jones, which are said to be "similar" to the Tasmanian . . .

Reference only, after Bonwick 1870

Richard Wallaschek, Anfänge der Tonkunst (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1903), 41

https://archive.org/stream/anfngedertonkuns00wall#page/41/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

From Wallaschek 1893, reference only, after Bonwick 1870

Alice M. Moyle, "Tasmanian music, an impasse?", Records of the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston 26 (May 1968), (1-18), 6, 17

From Bonwick 1870

Keith Vincent Smith and kathryn Lamberton (eds), Mari nawi: Aboriginal odysseys 1790-1850 (Sydney: State Library of New South Wales, 2010), 20

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/74VKMePLWedM

https://www2.sl.nsw.gov.au/archive/events/exhibitions/2010/mari_nawi/docs/marinawi_guide.pdf (DIGITISED)

Includes facsimile of Jones 1811, 15

Graeme Skinner, Toward a general history of Australian musical composition: first national music, 1788-c.1860 (Ph.D thesis, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, 2011), 62-63

http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7264 (DIGITISED)

Keith Vincent Smith, "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales", eBLJ (Electronic British Library Journal)

(2011, article 14), 1-7

http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle142011.pdf (DIGITISED)

Page 1 has facsimile of Jones 1811, 15, and page 7 embedded sound file of a 2010 performance of the song by Indigenous singers in Sydney (see sound above)

Keith Vincent Smith, "Tubowgule (Bennelong Point)", and "Bennelong's Song", in Ewen McDonald (ed.), Site (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012), [unpaginated]

https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/175905666

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=E0PIa25UCMAC&pg=PT93 (PREVIEW)

Includes facsimile of Jones 1811, 15 (96)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=E0PIa25UCMAC&pg=PT96 (PREVIEW)

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 367-68

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Commentary:

The music and words of this song were taken down by Edward Jones (1752-1824), a Welsh harpist, in London in mid 1793 from the singing of Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne, the two Wangal men who had been brought from Sydney to England by Arthur Phillip.

The words were also separately transcribed in or around Sydney by William Dawes (c. 1790/91), John Hunter (c. 1790/91), and David Collins (before 1796).

Keith Vincent Smith (2011) reliably fixed the performance at sometime between late May and October 1793, at or near the singers' then lodgings, in the house of William Waterhouse (father of Henry Waterhouse) at 125 Mount Street, Mayfair, near Berkeley Square, London. Smith discovered that Jones, Welsh harpist and bard to the prince of Wales (later George IV), was then living at 122 Mount Street.

References:

[Review of Jones 1811], The Monthly Magazine 34 (1 August 1812), 54

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=C2eP-ZRhnOwC&pg=PA54 (DIGITISED)

Musical Curiosities, or a Selection of National Songs and Airs, by Edward Jones, Bard to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent. 10s 6d.

Mr. Jones, of whose industry, as a gleaner of national music, we have often had occasion to speak, has furnished, in the present collection, a great number of popular, and some exceedingly curious, foreign and domestic airs. The whole occupies forty-two folio pages, and forms a body of variegated and well chosen melodies, that do much credit to the selector's judgment, and will be found highly acceptable to the public.

"IN MEMORY OF YEMMERRAWANNIE", The Register (24 April 1914), 12

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58499993 (DIGITISED)

Jack Brook, "The forlorn hope: Bennelong and Yemmerrawannie go to England", Australian Aboriginal Studies (2001), 36-47

http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=593850834183257;res=IELIND (PAYWALL)

. . . By 6 July 1793, the two 'Natives' had moved from their original lodging house to the residence of Mr. Waterhouse, Mount Street, Grosvenor Square, in the fashionable West End of London. They continued to have the services of a servant and their clothes were mended and washed as required. Books were acquired and a 'Reading Master' and a 'Writing Master' were hired to school the two men in those subjects. The education of his guests had always been the intention of Governor Phillip for, once they understood English, 'much information' could be obtained from them . . .

Kate Fullagar, "Bennelong in Britain", Aboriginal History 33 (2010), 31-51

http://doi.org/10.22459/AH.33.2010 (PDF FREE DOWNLOAD)

1802

3 2 songs

Dharug, Sydney area, NSW

Transcribed by Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846) and Pierre François Bernier (1779-1803), members of the Baudin expedition, from unidentified singers, probably in the Sydney area, between late June and November 1802; first published Paris, 1824

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#003 (shareable link to this entry)

Source:

Charles Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, Voyage de découvertes aux terres Australes; historique, atlas par MM. Lesueur et Petit, seconde édition (Paris: Chez Arthus Bertrand, 1824), plate 32, page 52, nos 1 and 2

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=aXVdAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA32 (DIGITISED)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/20117482

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-32726430 [plate only] (DIGITISED)

http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/98350 [plate only] (DIGITISED)

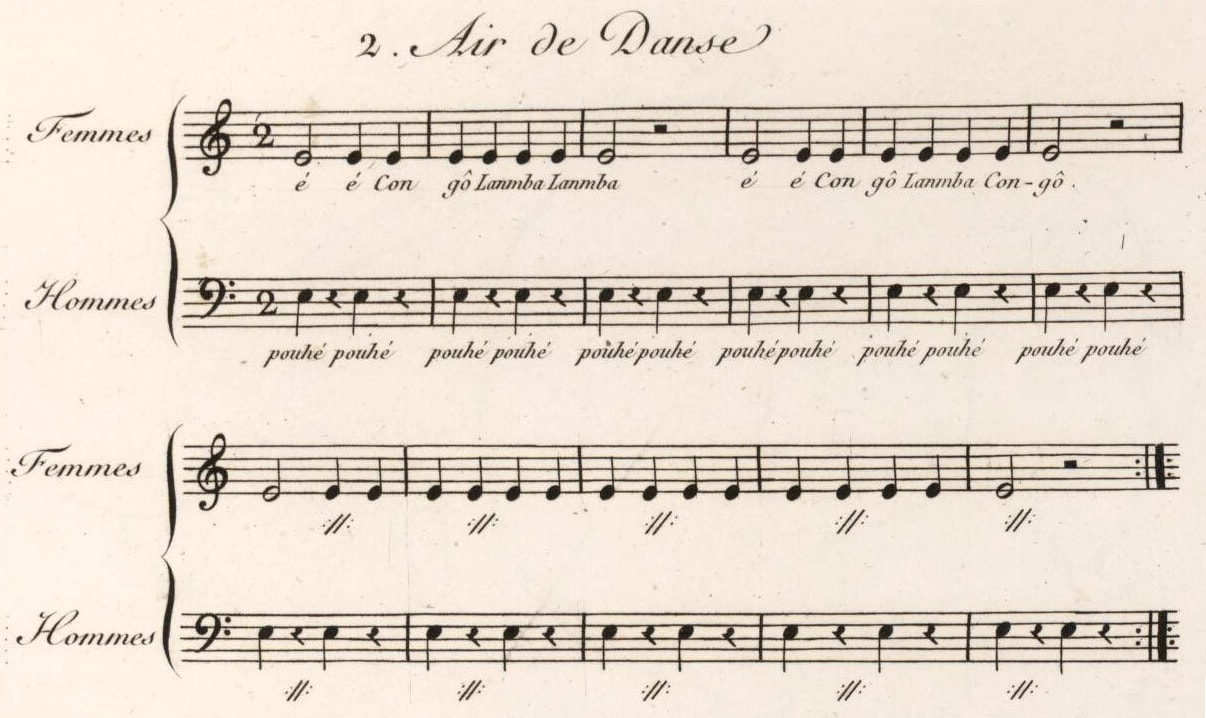

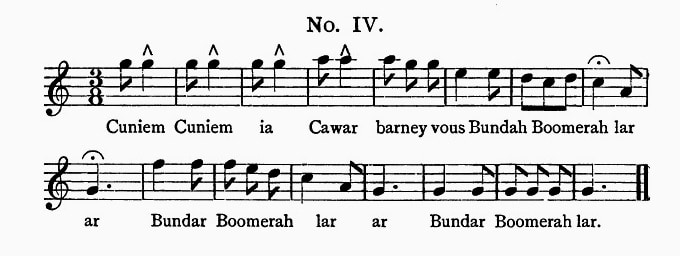

Musique des sauvages de la Nouvelle-Galles du Sud divers airs notés [table of contents]

[Pl.] 32

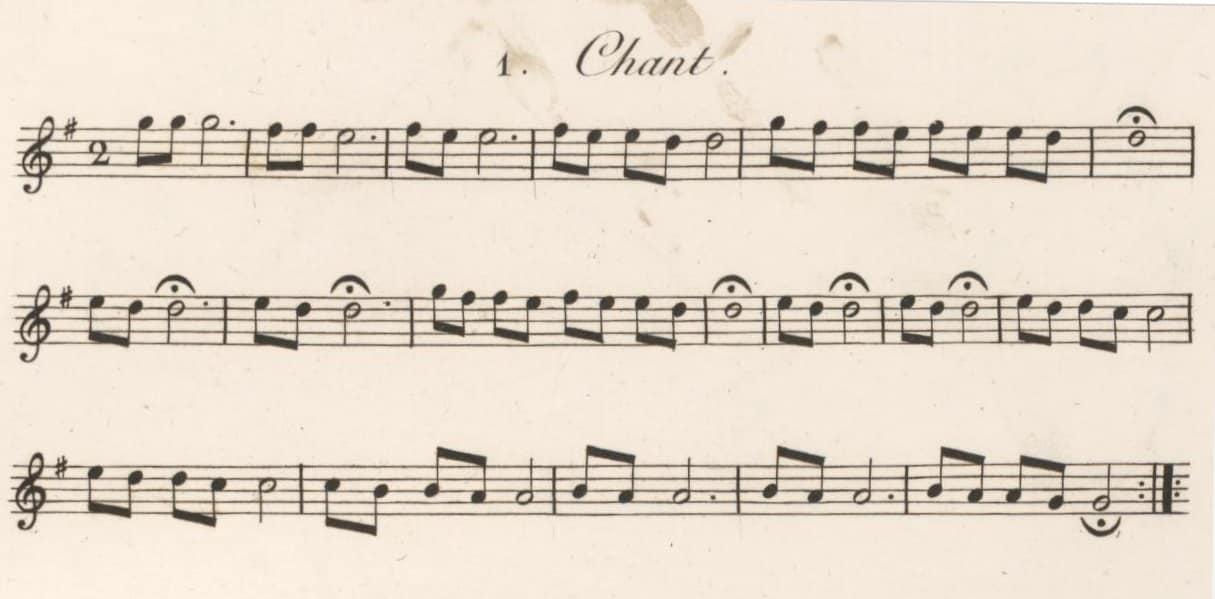

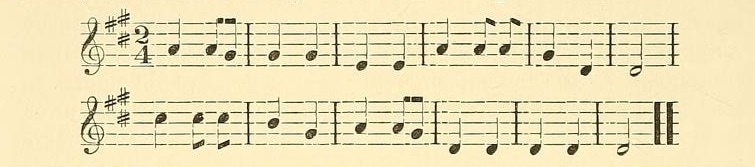

1 Chant [music only]

2 Air de danse [music and words]

é é Con gô Lanmba Lamnba é é Con gô Lanmba Con gô. [rep.]

pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé [reps.]

3 Cri de ralliement . . .

Lesueur et Bernier notaverunt . . .

Nouvelle-Hollande. N[ouv]elle Galles du Sud . . .

For no. 3 Cri de ralliement, see this page 1 above

3.1 Song

3.1 "1. Chant" ("song")

text: [music only, no words]

analytics: Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

3.2 Dance chant

3.2 "2. Air de danse" ("dance song")

text: [Women] é é Con gô Lanmba Lanmba é é Con gô Lanmba Con gô . . . [repeats]; [Men] pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé pouhé . . . [repeats] [notated in 2 parts, rhythms only, no melodies]

analytics: As for 3.1

Sound:

"GUYANAYA BAYUI: OLD PEOPLE, FUTURE", Deepening Histories (Australian National University)

Newly imagined performances in contemporary experimental idiom, by Richard Green, Karen Smith, Matt Doyle, Clarence Slockee, with Kevin Hunt, features Barabul-la (c.1790), Chant (1802), and Harry's Song (c.1820)

Bibliography and resources:

Louis de Freycinet, Voyage autour du monde entrepris par ordre du Roi . . . exécuté sur les corvettes de S. M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820, historique, tome deuxième - deuxième partie (Paris: Chez Pillet Ainé, 1839), tome 2, 2 part, 775

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA775 (DIGITISED)

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-32726166/view?partId=nla.obj-32726430#page/n1/mode/1up (PLATE ONLY)

No.3 Air (1839) = 1 Chant (1824), tranposed down a tone

Karl Hagen, Über die Musik einiger Naturvölker (Australier, Melanesier, Polynesier) (Dissertation, University of Jena) (Hamburg: Ferdinand Schlotke, 1892), 9-13 (commentary), plate II, example 5 (music)

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/30068490

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=L-saAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9 - commentary (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=L-saAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT4 - plate II (DIGITISED)

Richard Wallaschek, Primitive music: an inquiry into the origin and development of music, songs, instruments, dances, and pantomimes of savage races (London; New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893), 36-37 (commentary), [343] (music example 5.3)

https://archive.org/stream/primitivemusicin00wall#page/36/mode/2up commentary (DIGITISED)

https://archive.org/stream/primitivemusicin00wall#page/n343/mode/2up music example 5.3 (DIGITISED)

Example 5.3 ("Larghetto") = 3.1 above, from Freycinet 1839

Richard Wallaschek, Anfänge der Tonkunst (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1903), 36-37, 342

https://archive.org/stream/anfngedertonkuns00wall#page/36/mode/2up commentary (DIGITISED)

https://archive.org/stream/anfngedertonkuns00wall#page/342/mode/2up music example 5.3 (DIGITISED)

Example 5.3 ("Larghetto") = 3.1 above, from Freycinet 1839

Nicole Saintilan, "Music - if so it may be called": perception and response in the documentation of Aboriginal music in nineteenth century Australia (M.Mus thesis, University of New South Wales, 1993), 11-16

http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/50383 (DIGITISED)

Graeme Skinner, Toward a general history of Australian musical composition: first national music, 1788-c.1860 (Ph.D thesis, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, 2011), 62, 432

http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7264 (DIGITISED)

Keith Vincent Smith, "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales", eBLJ (Electronic British Library Journal) (2011, article 14), (1-7)

http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/pdf/ebljarticle142011.pdf (DIGITISED)

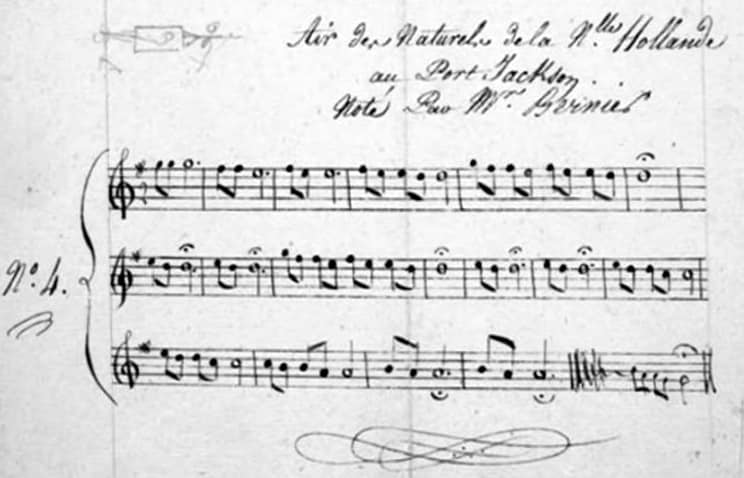

Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby, "Cross-cultural inquiry in 1802: musical performance on the Baudin expedition to Australia", in Kate Darian-Smith and Penelope Edmonds (eds), Conciliation on colonial frontiers: conflict, performance, and commemoration in Australia and the Pacific rim (New York and Oxford: Routledge, 2015), especially 24-25

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VVehBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA24 (PREVIEW)

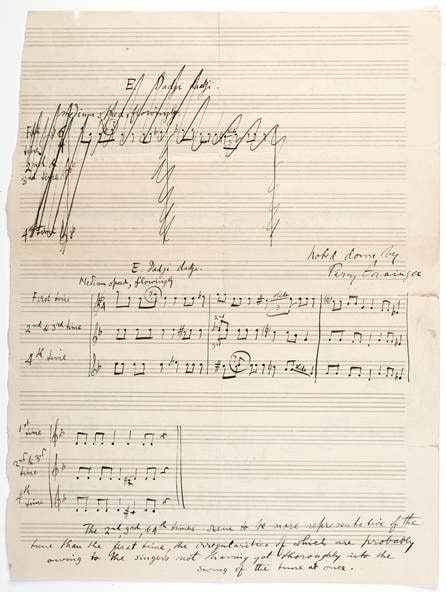

Page 24 reproduces (? Bernier's original) handwritten notation of the "Air des Naturels de la N[ouve]lle Hollande au Port Jackson" (below) and page 25 the copy text for the music plate of the Lesueur and Petit atlas of 1824 (Lesueur Collection, Muséum de l'Histoire Naturells, Le Harve, nos. 16057R , 16059-1)

Jean Fornasiero, Lindl Lawton, and John West-Sooby (eds), The art of science: Nicolas Baudin's voyagers 1800-1804 (Mile End: Wakefield Press, 2016), 21

A higher quality colour reproduction of a manuscript fair copy of Bernier's transcription of 3.1 (c.f. lower quality image in Fornasiero and West-Sooby 2015 above)

Vivonne Thwaites, "Discovering the art of Lesueur" (pages 4-11); and Jean Fornasiero, "Music from the Littoral" (30-35), in Vivonne Thwaites (curator) and Jean Fornasiero, Littoral [exhibition catalogue] (Hobart: Carnegie Gallery, 8 April-10 May 2010, Carnegie Gallery; Burnie: Burnie Regional Art Gallery, 30 July-12 September 2010)

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 368-69

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Commentary:

Noted down by members of Nicolas Baudin's expedition in NSW, Winter and Spring 1802, and added by Lesueur and Petit to the second edition of their Atlas (1824); some general details of the visit are discussed in the text of volume 1 of the set (Peron and Freycinet 1824).

References:

François Péron and Louis de Freycinet, Voyage de découvertes aux terres Australes: fait par ordre du gouvernement, sur les corvettes les Géographe, le Naturaliste, et la goëlette le Casuarina, pendant les années 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804; historique . . . seconde édition . . . tome 1 (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1824)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ZD8bAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR3 (DIGITISED)

c.1805

4 1 song

? Dharug, ? Sydney area, NSW

Music and words transcribed from unidentified singers, probably in the Sydney region, probably c.1800-05, and "brought over [to UK] by an officer from NSW"; first published in Britain (? Scotland, c.1802-10)

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#004 (shareable link to this entry)

Wahabindeh bang ha nel ha

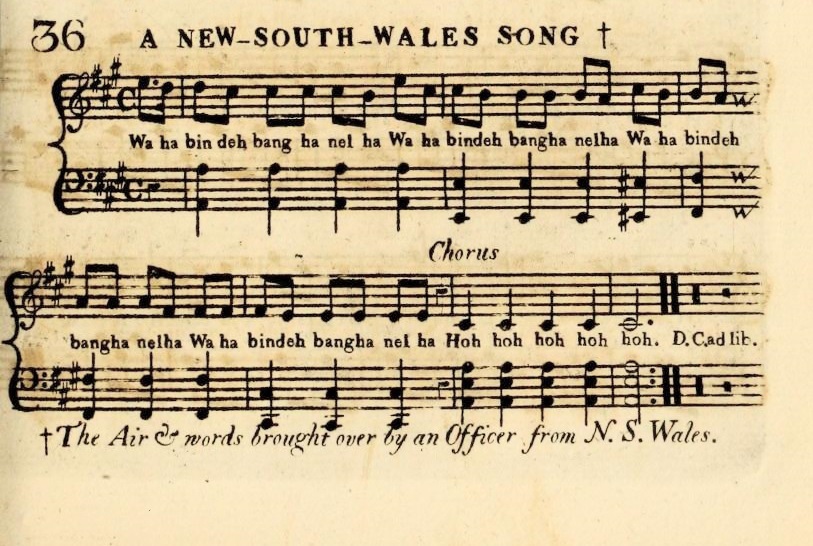

4 "A New-South-Wales song"

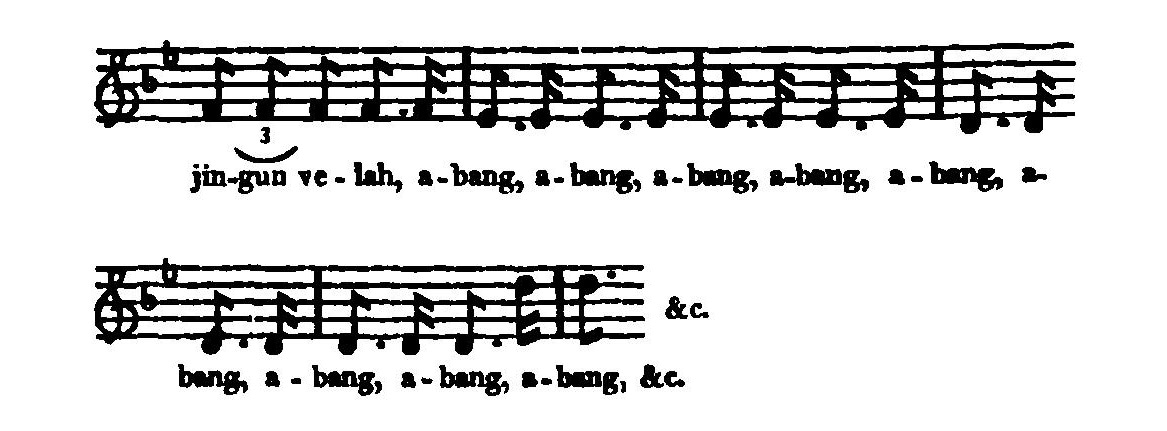

text: Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha Hoh hoh hoh hoh hoh hoh (D.C. ad lib.)

analytics: ? Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ ? Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ ? Dharug (language)

Source:

National Library of Scotland, Inglis Collection of printed music, Ing.72(1-3) [ID: 94733017], a composite music volume in 3 sections;

Section 3 (unidentified collection of "national music" of various nations, including glees, catches, rounds, etc., titlepage missing), No. 36, page [43]

http://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music/pageturner.cfm?id=94737053 (DIGITISED)

36 A NEW-SOUTH-WALES SONG. The Air & words brought over by an Officer from N. S. Wales.

Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha

Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha

Wa ha bin deh bang ha nel ha

Hoh hoh hoh hoh hoh hoh. (D.C. ad lib.)

Sound:

Melody only, synthesised using bass woodwind sounds as approximations for voices; synthesised sound file, Australharmony 2016

medialocal/1800-wa-ha-bin-deh-song.wav

Harmonised version, for piano, synthesised, Australharmony 2016

Bibliography and resources:

Graeme Skinner, "The invention of Australian music", Musicology Australia 37/2 (2015), 296-98

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2015.1076594 (PAYWALL)

ONSITE PDF (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 369

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Commentary (GS):

In November 2014, while searching on likely word strings for possible Australian material in the digital music archive of the National Library of Scotland, I stumbled across this elsewhere undocumented and previously unrecognised source of an early colonial transcription of the words and music of an Australian Indigenous song. So far as I have been able to establish (July 2015), no one has previously registered its existence part from the NLS's own autoscanners and cataloguers. So, as another example of a very early transcription and arrangement of melody and words of an Indigenous song, it seems, for Australian music history, to be an entirely new find.

Under the title "A New-South-Wales Song . . . Air & Words brought over by an Officer from N. S. Wales", it appears as number 36 of 79 extant items (Nos 1-79) in an unidentified and possibly incomplete 98-page mixed collection of airs and duets with instrumental basses, instrumental dances, and three- and four-part glees and rounds, lacking a titlepage or any other indication of its origins.

As well as familiar English, Scottish, Welsh, and Irish numbers, there are also 2 carols from the Orkneys, some Russian dances, numerous French and German songs in the original languages, the widely occurring Death Song of the Cherokees, and a keyboard arrangement of an "Hindoostan Air" called Dandee Kala, which had appeared previously (as as "Dande ka la") in Bird's Oriental Miscellany (1789).

One item fixes the collection's publication date at no earlier than 1802. Item 34, a curious Runa of the Finlanders, in 5/4 time, was, as the source acknowledges, excerpted from Joseph Acerbi's Travels through Sweden, Finland and Lapland, published in London in 1802. There the same Runa appears on page 324 as the first items in an extensive music supplement to the second volume, signed at the end "Engrav'd by E. RILEY, No 8, Strand" (336).

A comparison of shows that the two are not only musically identical but also similar enough in format and detail for both to be the work of Edward Riley (1769-1829). Having already engraved it for Acrebi's book, he plausibly included it again in this collection, either to be issued under his own imprint, or perhaps engraved by him for another publisher. If so, since Riley sold up his music retail and publishing business and left London for New York by 1805 (possibly earlier), and assuming that this collection was indeed as most likely published in Britain, we could date the unidentified collection certainly to after 1802, and probably to before 1805.

The earliest music-and-words transcription of an Indigenous Australian song known to survive is A song of the natives of New South Wales (see 2 above), taken down in London in 1793 from the singing of Bennelong and Yemmeroweney; however, Jones published it only 18 years later, in 1811. Likewise, the three music-and-words transcriptions taken down by members of the Baudin expedition in 1802 (see 1 above and 3 above) were not published until 1824. So, if not the earliest taken down, it is, unless another so far unknown early example is belatedly discovered, the earliest in print, probably by at least five or six years.

Of the otherwise unidentified "Officer from N. S. Wales" by whom the "air and words were brought over" from New South Wales back to Britian, a retiring member of the NSW Corps, or a returning naval officer, are possible candidates.

Despite the fact that the song appears to have been imperfectly observed and somewhat remodelled, the melodic contour and the short, repeated text seem to be at least vestigially authentic.

References:

Special collections of printed music (digitised), Glen and Inglis collections of printed music, National Library of Scotland

http://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music

No. 34, page [41], "Runa of the Finlanders"

http://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music/pageturner.cfm?id=94737029 (DIGITISED)

No. 60, page [75] "The Death Song of the Cherokees"

http://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music/pageturner.cfm?id=94737437 (DIGITISED)

No. 66 (page [81]) "Dandee Kala. Hindoostan Air"

http://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music/pageturner.cfm?id=94737509 (DIGITISED)

"Dande ka la", in William Hamilton Bird (ed.), The oriental miscellany (Calcutta: Jo[se]ph Cooper, 1789), 18

https://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/244380 (DIGITISED)

Joseph Acerbi, Travels through Sweden, Finland and Lapland . . . vol. 2 (London: Printed for Joseph Mawman, 1802), 325, 336

https://archive.org/stream/travelsthroughsw02inacer#page/325 (DIGITISED)

https://archive.org/stream/travelsthroughsw02inacer#page/336 (DIGITISED)

"Riley, Edward", in Frank Kidson, British music publishers, printers and engravers . . . (London: W. E. Hill, 1900), 110

https://archive.org/stream/cu31924021638402#page/n125/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

"Riley, Edward, sen.", in Nancy Groce, Musical instrument makers of New York: a directory of eighteenth and nineteenth century urban craftsmen (New York: Pendragon Press, 1999), 131

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=EjYjD4vQbCYC&pg=PA131 (PREVIEW)

Wendell Dobbs, "An early American family of flutists", The Flutist Quarterly (Fall 2008), 40-44

http://mds.marshall.edu/music_faculty/1

"Riley, Edward (b. England, 1769; d. Yonkers, NY, 18 Aug 1829). Music engraver and publisher, teacher, and composer, of English birth", The Grove Dictionary of American Music (2nd edition, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013)

1819

5 2 songs

Dharug, Sydney area, NSW

Music (and words for 5.2) transcribed by, or on behalf of, Louis de Freycinet (1779-1842), Sydney area, between 19 November and 25 December 1819; first published Paris, 1839

Words of 5.2 also recorded earlier by (1) John Hunter, from the singing of Bennelong (published 1793); and (2) David Collins (published 1798)

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#005 (shareable link to this entry)

Source and documentation (5.1 and 5.2):

Louis de Freycinet, Voyage autour du monde entrepris par ordre du Roi . . . exécuté sur les corvettes de S. M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820, historique, tome deuxième - deuxième partie (Paris: Chez Pillet Ainé, 1839), 771-75 (commentary and music)

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA772 (DIGTISED)

[771] . . . Réunions de famille. - Les individus dont chaque tribu se compose [772] se rassemblent à diverses saisons de l'année, soit pour se consulter dans les affaires de quelque importance, soit pour se réjouir à l'occasion de certaines têtes. Cependant, quoiqu'il y ait communauté d'intérêt dans ces réunions, chaque famille est obligée d'avoir son feu à part et de pourvoir à sa subsistance. Cette règle est générale, hormis le cas où l'on fait la grande chasse aux kanguroos, à laquelle toute la tribu doit coopérer; aussitôt que le gibier a été cerné et pris en suffisante quantité, on le partage de bonne foi, et chacun s'en régale: telle est la fête des kanguroos.

Les autres fêtes des naturels ont toutes pour objet de manger et de danser ensemble, pendant plusieurs jours de suite. C'est tantôt la fête des huîtres, et alors ils se réunissent sur un point où ils puissent se procurer en abondance cet excellent coquillage; d'auïres fois c'est la fête des fougères ou celle [?] lis, et alors la racine du premier, ou la tige du second de ces végétaux, fait les frais du festin.

Il seroit difficile, dans ces circonstances, de persuader à un naturel de ne pas se joindre à ses compatriotes, ou même de se séparer d'eux pendant l'assemblée, quel que fût d'ailleurs le motif qu'on voulût faire valoir.

Une baleine échoue-t-elle sur la côte, tous les habitans d'alentour, qui en sont bientôt informés, se pressent autour du monstre, puis comme autant de loups affamés, ils s'acharnent sur la bête sans la quitter, tant qu'il en reste quelque débris: c'est ce qu'on nomme fête de la baleine. En pareil cas, on a vu plusieurs tribus distinctes se grouper sur le même point; mais il n'est pas rare que de telles réjouissances soient troublées par des altercations graves et même par des engagemens meurtriers.

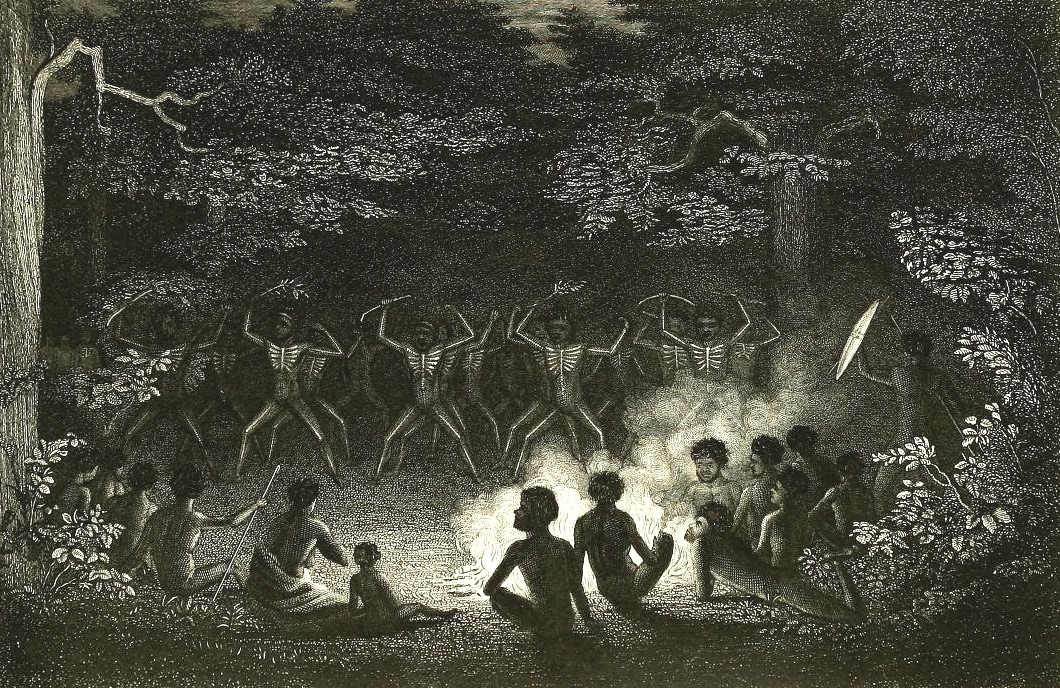

Danses. - Les autres fêtes dont nous avons parlé sont toujours plus pacifiques, et solennisées par des danses de nuit ou korroberis, pour lesquelles les indigènes sont extrêmement passionnés. Jamais ils ne s'y rendent sans se peindre le corps et la face de blanc et de rouge, ainsi que nous l'avons exposé ailleurs. L'éclat d'un vaste brasier donne un effet pittoresque à cette scène sauvage; et la danse bientôt animant les acteurs, les conduit graduellement à une sorte d'enthousiasme.

La coutume est de danser ainsi la nuit autour d'un feu, toutes les . . .

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA773 (DIGITISED)

fois qu'il survient un événement heureux ou remarquable. Cette danse est très-curieuse et amusante à voir; le pas général consiste à ployer les genoux en tenant un peu ies jambes écartées, puis à les remuer avec une sorte de tremblement ou de mouvement convulsif; le ployement des jambes et le trémoussement du corps ressemblent beaucoup à la danse de nos pantins. Les figurans rapprochent par momens leurs genoux avec vivacité, et font claquer les unes contre les autres, d'une manière assez forte, les parties internes et charnues de leurs cuisses et de leurs mollets. Ils changent de temps en temps de place, avec une confusion apparente; mais bientôt accouplés de deux en deux, on les voit se ranger avec promptitude, en une phalange régulière, sur cinq ou six personnes de hauteur.

Pendant ces korroberis, les femmes chantent en battant la mesure avec deux morceaux de bois. Une partie des danseurs fait entendre, par intervalles, sur un ton grave et non interrompu, les mots détachés prou, prou, prou, auxquels succède bientôt un grognement, qui imite celui du kanguroo, peu différent de celui d'un porc. Pour l'ordinaire la danse continue ainsi jusqu'à ce que la fatigue les oblige à s'arrêter; ils se retournent alors, sens devant derrière, et se séparent en poussant un grand cri, terminé par de bruyans éclats de rire.

Les femmes, en de telles occasions, se tiennent toujours séparées des hommes, et forment entre elles des danses à côté de leurs maris, qui ont beaucoup d'analogie avec celle que nous venons de décrire.

Pendant la guerre, et avant d'en venir aux mains, les tribus ennemies se divertissent encore les unes en présence des autres, mais sans se mêler; au reste, dans leurs danses, dans leur manière d'annoncer qu'on est prêt à commencer, et dans les chansons qui les accompagnent, il y a des différences plus ou moins marquées, suivant les tribus.

Des korroberis ont encore lieu la veille du jour où un duel se prépare; mais ici les champions qui doivent combattre prennent tous deux part à la fête, et dorment ensuite l'un à côté de l'autre, comme si nulle inimitié n'existoit entre eux.

Nous avons vu des danses tout-à-fait du même genre exécutées par les sauvages de la baie des Chiens-Marins (pl, 12); le capitaine P. P. King . . .

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA774 (DIGITISED)

en a observé aussi de pareilles chez les habitans de l'île Melville, à la Terre d'Arnheim [Voyez King's Voyage to Australia].

Jeux. - Les naturels ont encore certaines réunions pacifiques où les plaisirs de la table n'ont aucune part, et dont l'objet est de se livrer à différens jeux. Tantôt c'est une boule grossière qu'ils se lancent de l'un à l'autre, tandis qu'une rangée de joueurs s'efforcent de l'atteindre au passage avec un bâton; ils excellent dans cet exercice qu'ils aiment beaucoup. Tantôt ils s'amusent à courir ou à lutter ensemble, pour mesurer leur force et leur adresse. Des chanteurs ambulans viennent aussi parfois égayer ces sortes de réunions.

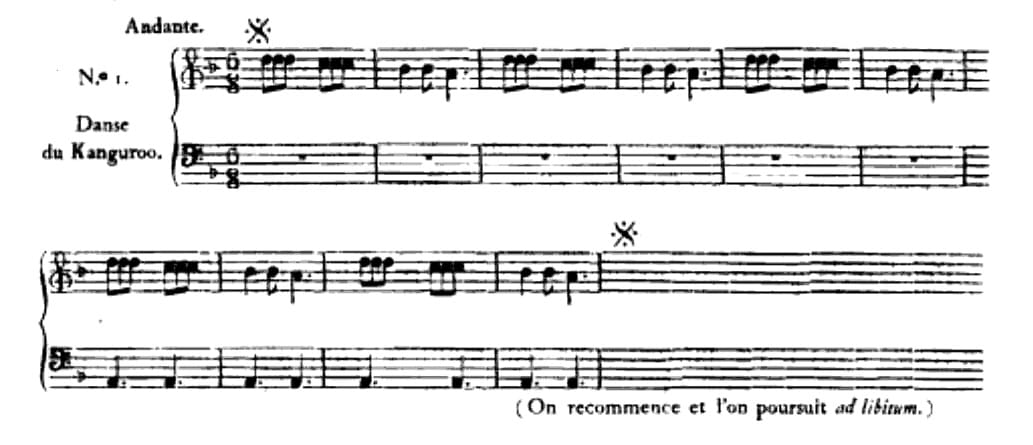

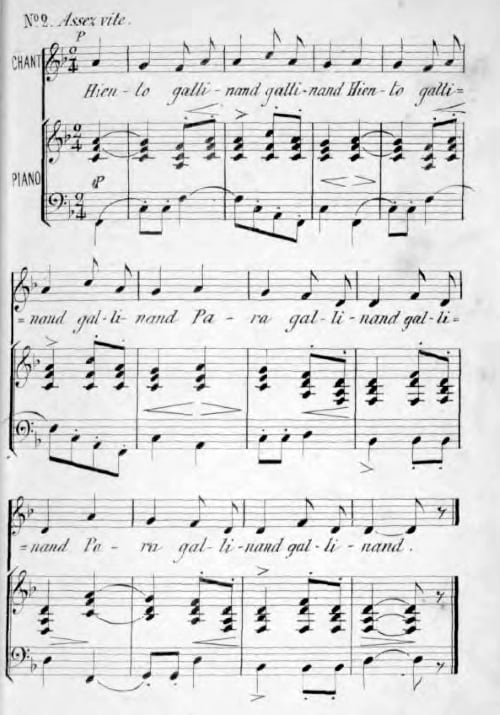

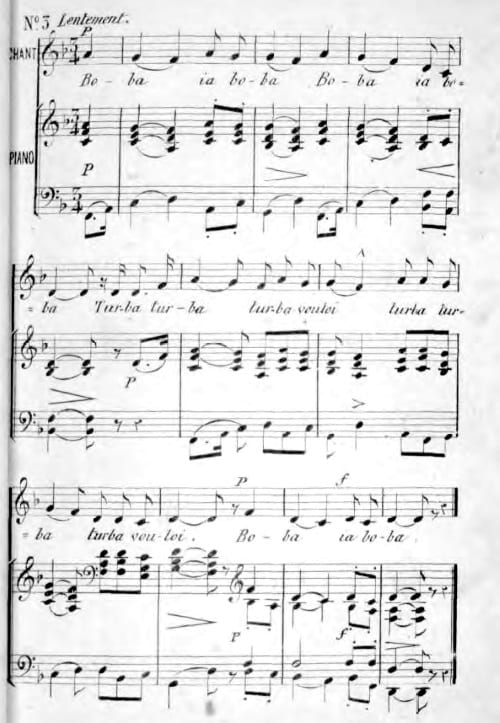

Musique. - En général, les aborigènes ont l'oreille juste, quoique leur musique, on peut le présumer, ne soit ni savante ni très-variée. J'en donne ici quelques échantillons. Les deux premiers sont des airs de danse; le troisième, une chanson dont les paroles me sont inconnues; celui qui vient ensuite, un chant particulier des femmes qui vont à la pêche; et le dernier, le cri que font les sauvages pour se reconnoître de loin.

[Footnote] L'air no. 2 a été noté par M. Field, et les no. 3 et 5 par M. Lesueur, à l'époque du voyage de Baudin aux Terres Australes.

5 MUSIC EXAMPLES (note, that of the 5 music examples, only nos. 1 and 4 are first published here; for sources of the other 3 see here below)

No. 1 Danse du Kanguroo = 5.1 below

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=pWNNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA775 (DIGITISED)

No. 2 Air de danse, from Field 1825, see 6 below

No. 3 Air, from Lesueur and Petit 1824 = 3.1 above

No. 4 Air de pêche = 5.2 below

No. 5 Cri pour se reconnoître de loin (Kou-hi), from Lesueur and Petit 1824 = 1 above

Instrumens de musique. - Doit-on donner le nom d'instrument de musique aux deux simples morceaux de bois dont les femmes, comme nous venons de le voir, se servent pour battre la mesure? Collins en cite une autre sorte, d'un mètre de longueur, taillé à trois faces, par l'une desquelles on le tient; les deux autres sont grossièrement ciselées en lignes onduleuses, et l'on frappe dessus avec un casse-tête.

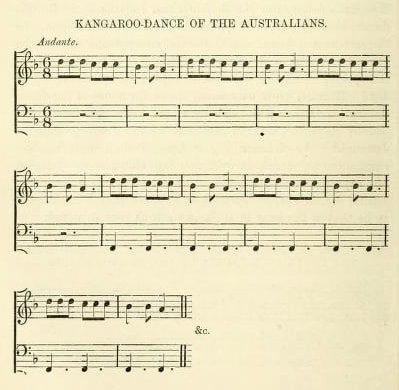

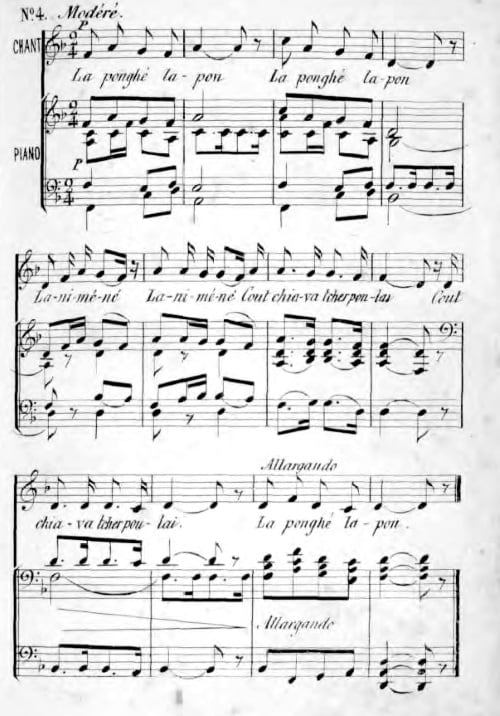

5.1 Kangaroo dance-song

5.1 "No. 1. Danse du Kanguroo" ("Kangaroo dance")

text: [music only, no words]

analytics: Sydney area (region); ECA (music region); South-eastern PN/ Yuin-Kuri [Sydney subgroup]/ Dharug (language)

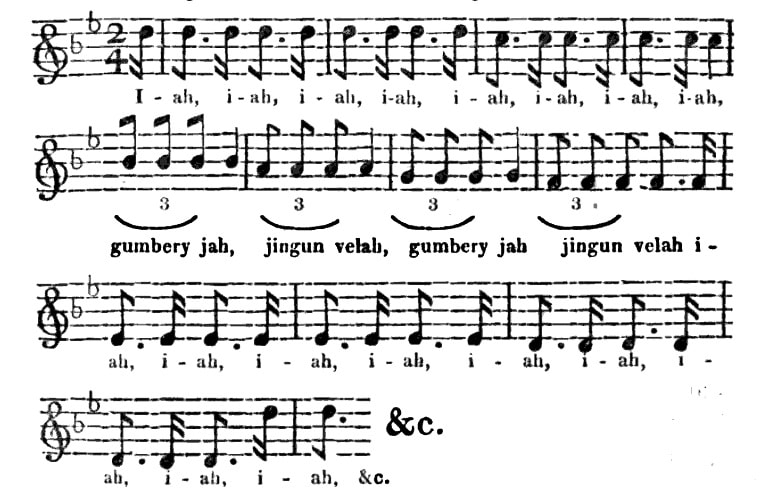

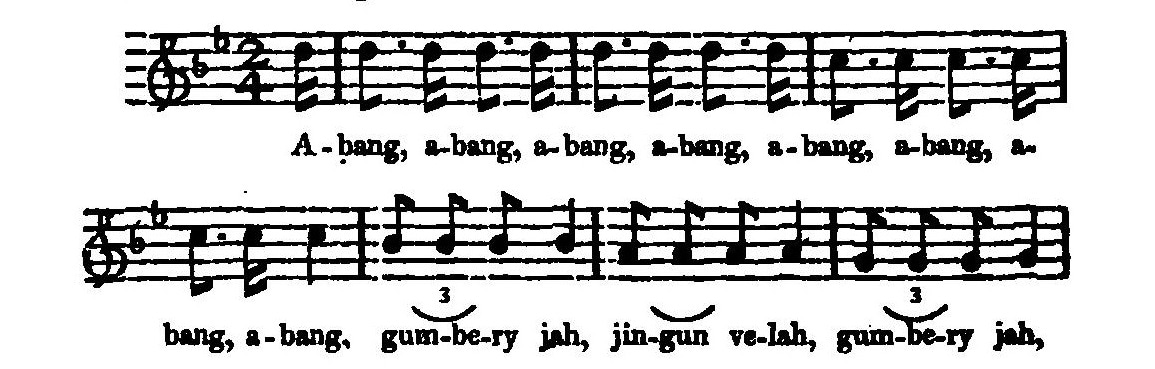

5.2 Fishing song

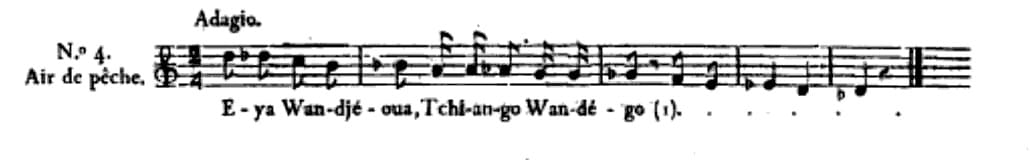

5.2 "No. 4. Air de pêche" ("Fishing song")

text: E-ya Wan-djé-oua, Tché-en-go Wan-dé-go . . . ["Je n'ai pu avoir les dernières paroles de cet air"]

analytics: As for 5.1

No 4. Air de pêche. E-ya Wan-djé-oua. Tchi-an-go Wan-dé-go [Je n'ai pu avoir les dernières paroles de cet air.]

Other sources and documentation (5.2):

John Hunter, An historical journal of the transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island . . . [full version] (London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1793), 413-14 (5.2 words only)

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/1bGMdJXY/XBj3Bol5keJyQ (DIGITISED - PAGE 413)

[413] . . . He [Bennelong] calls Governor Phillip, Beanga (father); and names himself Dooroow (son): the judge and commissary [David Collins] he calls Babunna (brother). He sings a great deal, and with much variety: the following are some words which were caught -

"E eye at wangewah-wandeliah chiango wandego mangenny wakey angoul barre boa lah barrema" . . .

NOTE: For the remaining text see 2 above

David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales: with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country . . . (London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, 1798), 616 (5.2 words only)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eRZcAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA616 (DIGITISED)

Words of a Song:

Mang-en-ny-wau-yen-go-nah, bar-ri-boo-lah, bar-re-mah.

This they begin at the top of their voices, and continue

as long as they can in one breath, sinking to the lowest note, and then rising again to the highest. The words are the names of deceased persons.

E-i-ah wan-ge-wah, chian-go, wan-de-go. The words of another song, sung in the same manner as the preceding, and of the same meaning. I met with only two or three words which bore a resemblance to any other language.

NOTE: For the remaining text see 2 above

David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales . . . (1798) [as above], 592-93

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eRZcAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA592 (DIGITISED)

. . . I had long wished to be a witness of a family party, in which I hoped and expected to see them divested of that restraint which perhaps they might put on in our houses. I was one day gratified in this wish when I little expected it. Having strolled down to the Point named Too-bow-gu-lie, I saw the sister and the young wife of Ben-nil-long coming round the Point in the new canoe which the husband had cut in his last excursion to Parramatta. They had been out to procure fish, and were keeping time with their paddles, responsive to [593] the words of a song, in which they joined with much good humour and harmony. They were almost immediately joined by Ben-nil-long, who had his sister's child on his shoulders. The canoe was hauled on shore, and what fish they had caught the women brought up. I observed that the women seated themselves at some little distance from Ben-nil-long, and then the group was thus disposed of - the husband was seated on a rock, preparing to dress and eat the fish he had just received. On the same rock lay his pretty sister War-re-weer asleep in the sun, with a new born infant in her arms; and at some little distance were seated, rather below him, his other sister and his wife, the wife opening and eating some rock-oysters, and the sister suckling her child, Kah-dier-rang, whom she had taken from Ben-nil-long . . .

David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales . . . (1798) [as above], 601

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=eRZcAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA601 (DIGITISED)

. . . As they never make provision for the morrow, except at a whale-feast, they always eat as long as they have any thing left to eat, and when satisfied, stretch themselves out in the sun to sleep, where they remain until hunger or some other cause calls them again into action. I have at times observed a great degree of indolence in their dispositions, which I have frequently seen the men indulge at the expence of the weaker vessel the women, who have been forced to sit in their canoe, exposed to the fervour of the mid-day sun, hour after hour, chaunting their little song, and inviting the fish beneath them to take their bait; for without a sufficient quantity to make a meal for their tyrants, who were lying asleep at their ease, they would meet but a rude reception on their landing.

David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales, from its first settlement in January 1788 to August 1801 . . . second edition (London: For T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1804), 387

https://archive.org/stream/AccountEnglishC00Coll#page/n455/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

. . . As they never make provision for the morrow, except at a whale-feast, they always eat as long as they have any thing left, and when satistied, stretch themfelves out in the sun to sleep, where they remain until hunger or some other cause calls them again into action. The men frequently indulge a great degree of indolence at the expence of the women, who are compelled to sit in their canoe, exposed to the fervour of the mid-day sun, hour after hour, chaunting their little song, and inviting the fish beneath them to take their bait; for without a sufficient quantity to make a meal for their tyrants, who are lying asleep at their ease, they would meet but a rude reception on their landing . . .

Bibliography and resources:

Carl Engel, An introduction to the study of national music: comprising researches into popular songs, traditions, and customs (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1866), 238 (music image above)

https://archive.org/details/introductiontost00enge/page/238/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=0k4QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA238 (DIGITISED)

. . . The Kangaroo dance of the natives of Australia is performed by the men only, while the women are singing and beating time by striking two pieces of wood together. The dancers imitate the grunting of the kangaroo, whereby they produce a kind of bass to the singing of the women, as shown in the following notation, which is taken from Freycinet's "Voyage autour du Monde."

KANGAROO-DANCE OF THE AUSTRALIANS . . .

Reproduces music of 5.1 Danse du Kanguroo

James Bonwick, Daily life and origins of the Tasmanians (London: Samson, Low, Son, and Marston: 1870), 31

https://archive.org/stream/dailylifeandori02bonwgoog#page/n50/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=rQ5zAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA31 (DIGITISED)

But Captain Freycinet has given us a true Tasmanian tune of the oldest date [MUSIC EXAMPLE]

Reproduces, without title, melody of 1 Kangaroo dance from Freycinet 1839 (? from Engel 1866)

C. Hubert H. Parry, The art of music (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, & Co., 1893), 54

https://archive.org/stream/artofmusic00parrrich#page/54/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

Parry, The art of music (1897), 49, and many later editions

https://archive.org/stream/evolutionofartof00parruoft#page/49/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

Reproduces, without title, first four bars of melody of 1 Kangaroo dance from Engel 1866

Nicole Saintilan, "Music - if so it may be called": perception and response in the documentation of Aboriginal music in nineteenth century Australia (M.Mus thesis, University of New South Wales, 1993), 11-15

http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/50383 (DIGITISED)

Graeme Skinner, Toward a general history of Australian musical composition: first national music, 1788-c.1860 (Ph.D thesis, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, 2011), 433

http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7264 (DIGITISED)

Graeme Skinner, "The invention of Australian music", Musicology Australia 37/2 (2015), 296

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2015.1076594 (PAYWALL)

ONSITE PDF (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Graeme Skinner and Jim Wafer, "A checklist of colonial era musical transcriptions of Australian Indigenous songs", in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia (Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, 2017), 369-70

http://hdl.handle.net/1885/132161

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132161/26/17_skinner_wafer.pdf (FREE DOWNLOAD)

Commentary:

Five music examples were printed in Freycinet's 1839 published account of his 1819 return visit to Australia (19 November to 26 December), but of these only nos. 1 and 4 appeared for the first time.

As noted in the respective entries, nos. 3 and 5 were reproduced belatedly in the published reports of the 1802 visit of the Baudin expedition (Lesueur and Petit 1824; for no. 3 see 3.1 above, and for no. 5 see 1 above); and No. 2 was taken from Field 1825 (see 6 below).

Freycinet's accompanying account of Indigenous music making, and "korroberis" also draws partly on some later sources, such as Dawson 1830 (cited by Freycinet elsewhere, though not specifically in this instance). As evidence of the breadth of his more recent reading, Freycinet (830) also noted the existence of John Lhotsky's 1834 transcription (see below), in order to correct Lhostky's claim that his was the "premiere spécimen de musique australienne", by citing the priority of the transcriptions made for Baudin in 1802 (Lesueur and Petit 1824) and by Barron Field (citing Field 1825, but not Field 1823).

In his account of this 1819 visit, Freycinet recorded social and scientific contacts with Macquarie, Field, and many leading colonists. But in preparing the 1839 printed account, he also noted more recent reports (from the 1830s) of music in the theatre and concerts among the dilettanti (872-73) and in school education (881-82).

Collins 1798 also describes a women's fishing song.

Kangaroo songs and dances were widely documented, from Tasmania to Western Australia, for instance:

Bonwick 1870 (31) claimed, on no evidence other than that Kangaroo dances were also performed in Tasmania, that the Kangaroo dance melody from Freycinet 1839 is "a true Tasmanian tune of the oldest date".

There are two other, much earlier transcriptions of words of the fishing song, 5.2, in Hunter 1793 (413) and Collins 1798 (616) (see below); our thanks to Tom Allinson (producer of the History Lab, 2SER 107.3FM) for bringing this to our attention (July 2018).

References:

"Ship News", The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (20 November 1819), 3

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2179095 (DIGITISED)

The French corvette l'Uranie, Captain FRECINET, arrived on Thursday, engaged in a voyage of discovery, with many Officers in the various departments essential to a voyage of this general utility to the world at large. The Officers accompanying Captain Frecinet, who 17 years ago visited this Colony, as we are given to understand with Commodore Baudin, on his voyage of discovery into these seas with the Geographe and Naturaliste, are Gentlemen of the most kind and polished manners; which mention may be considered as a redundancy of expression as affects the Gentlemen of any Nation; but the descriptive writer cannot avoid observations which are so pleasing to the polished circle, and accord so sensibly with the feelings of a refined and liberal Nation.

"Ship News", The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (25 December 1819), 2

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2179163 (DIGITISED)

Sailed this day to resume her voyage of discovery, the French corvette l'Uranie, commanded by Monsieur Freycinet. On getting under weigh, she saluted the fort, which was returned by the battery from Dawes' Point.

Robert Dawson, The present state of Australia a description of the country, its advantages and prospects, with reference to emigration: and a particular account of the manners, customs, and condition of its Aboriginal inhabitants (London: Smith, Elder, 1830)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=5ngIAAAAQAAJ (DIGITISED)

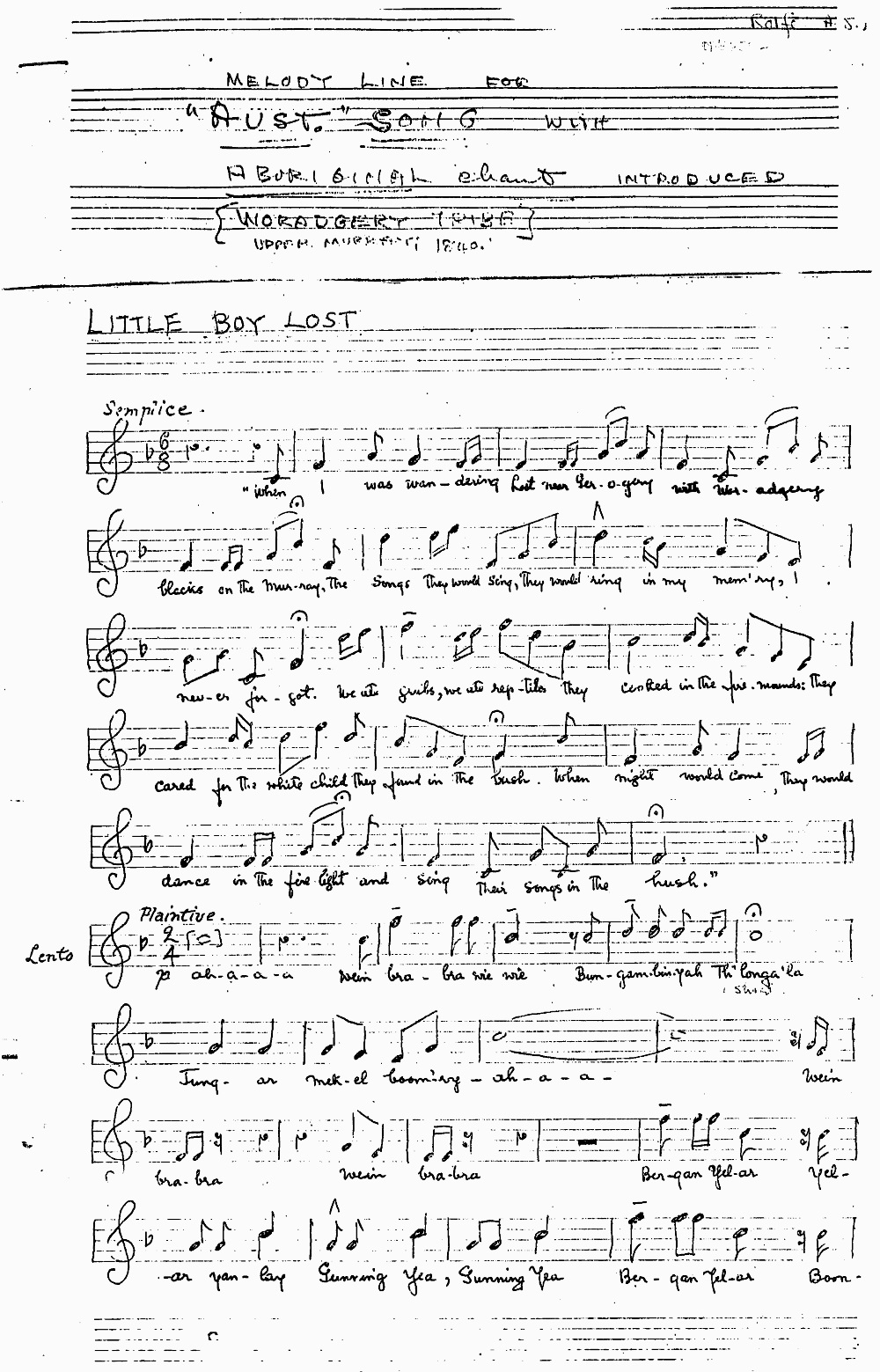

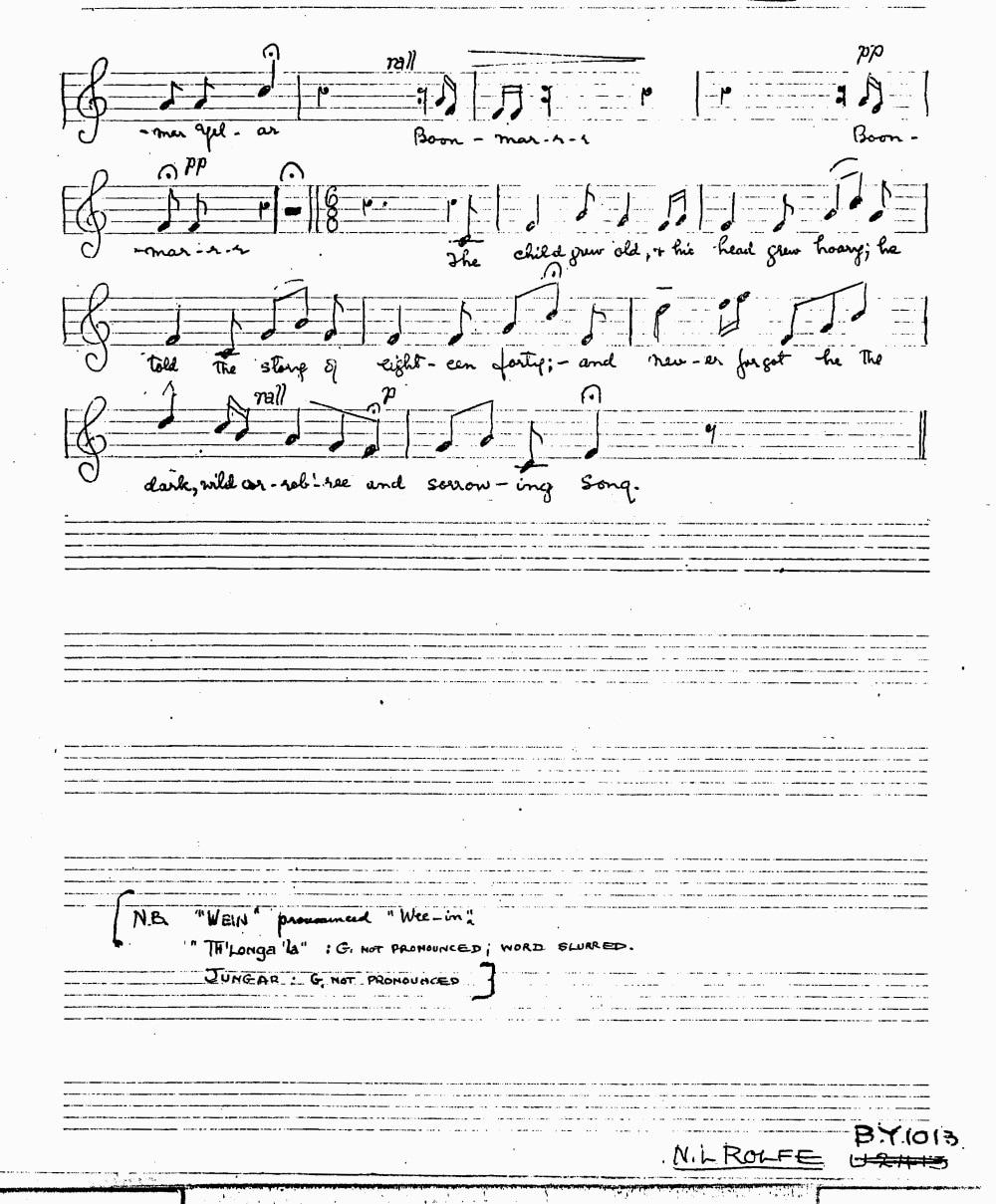

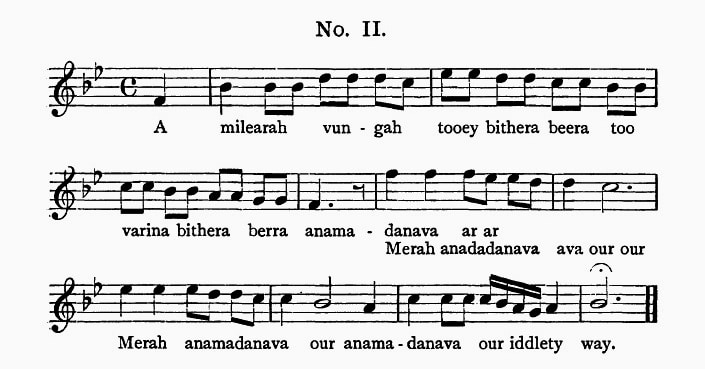

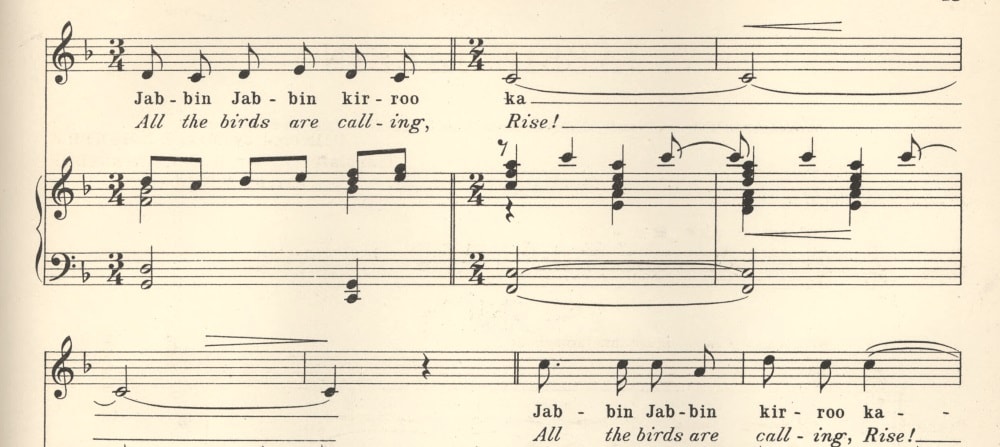

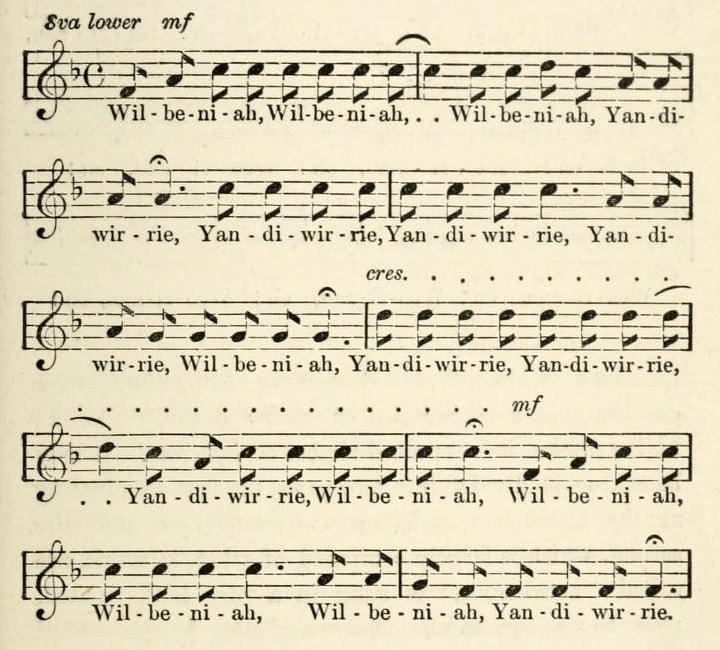

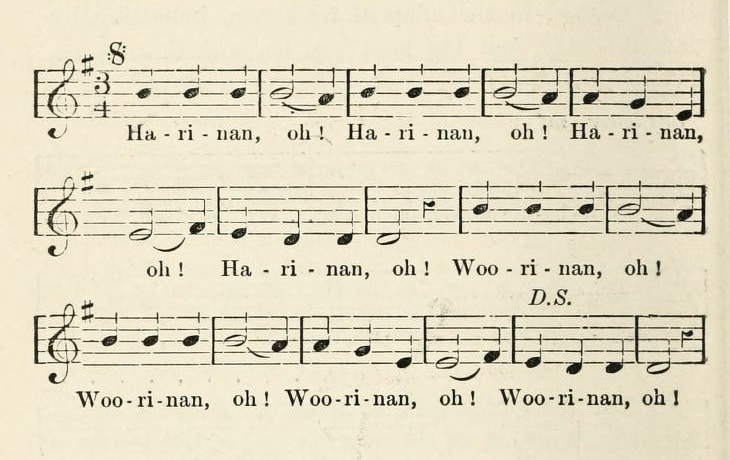

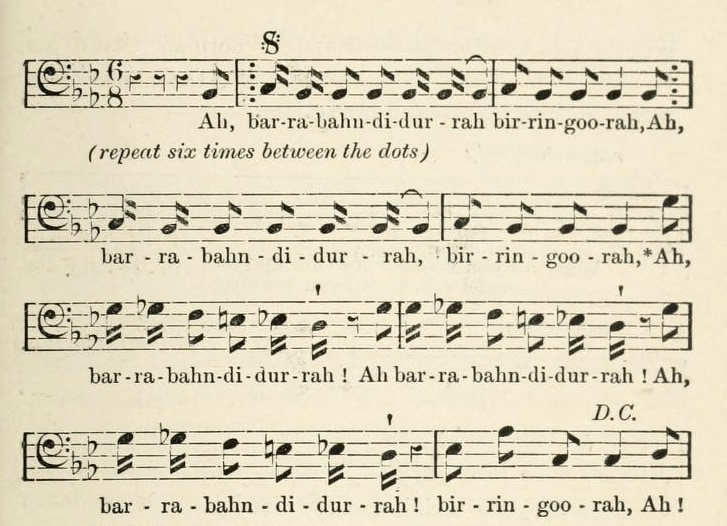

c.1820

6 1 song

Dharug, Sydney area, NSW

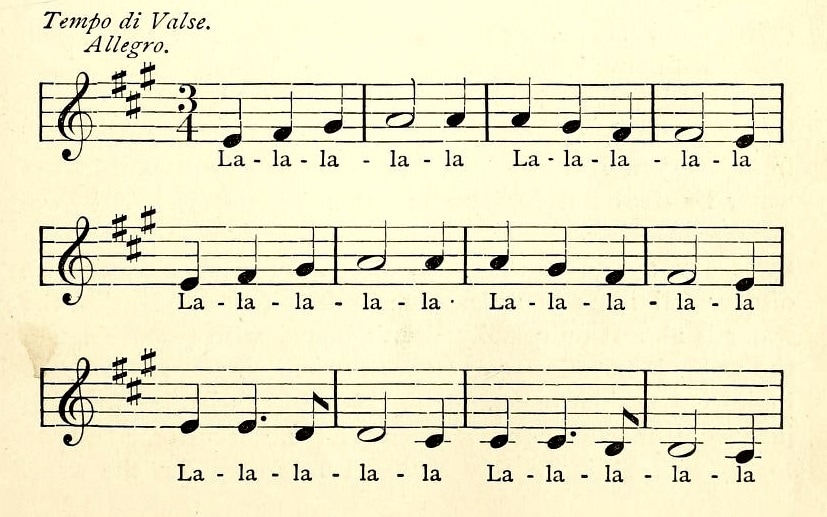

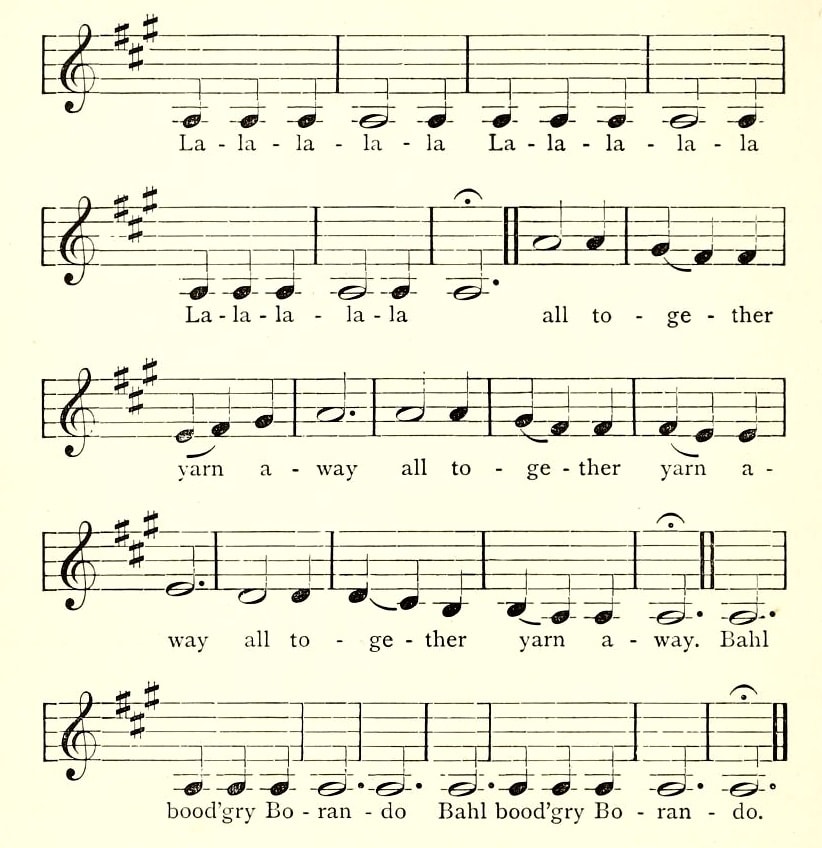

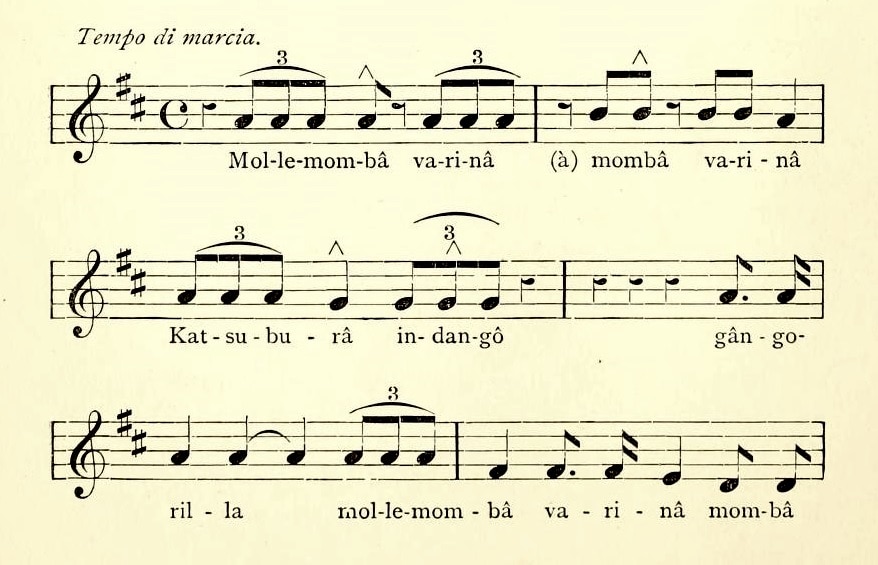

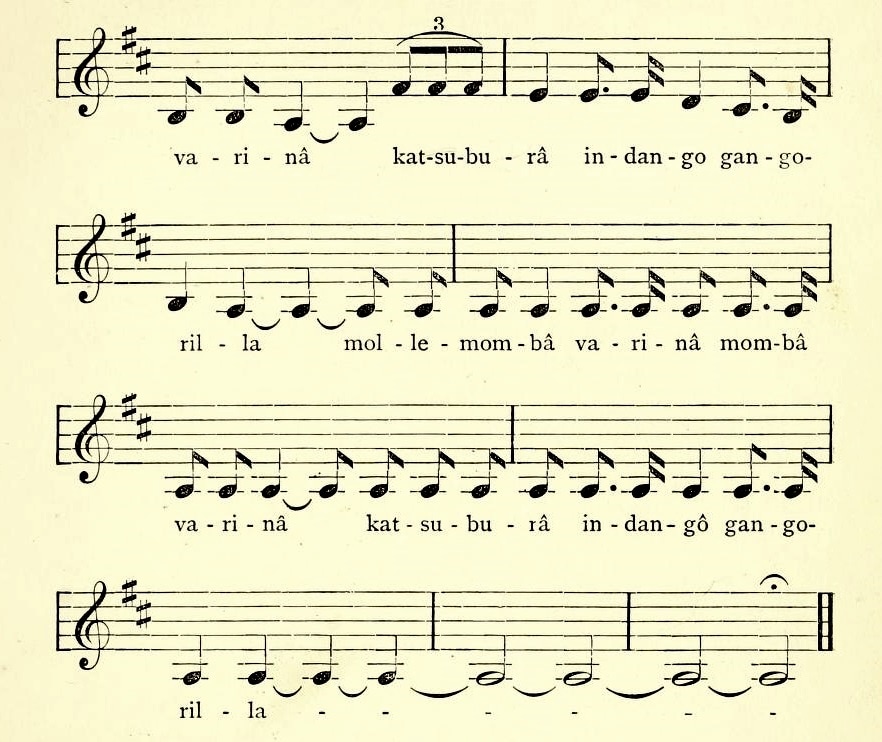

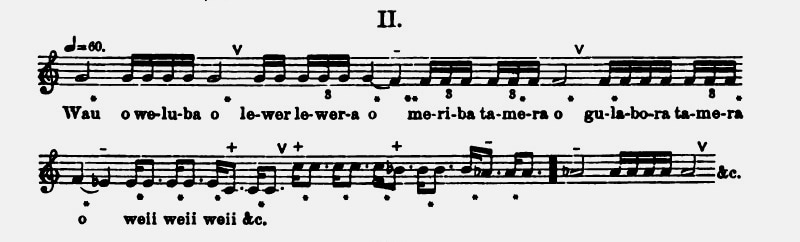

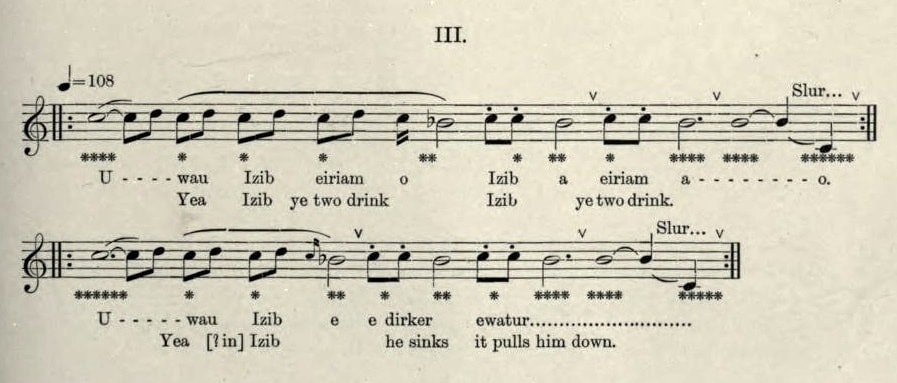

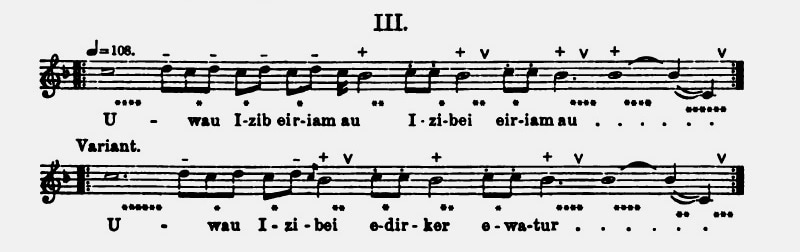

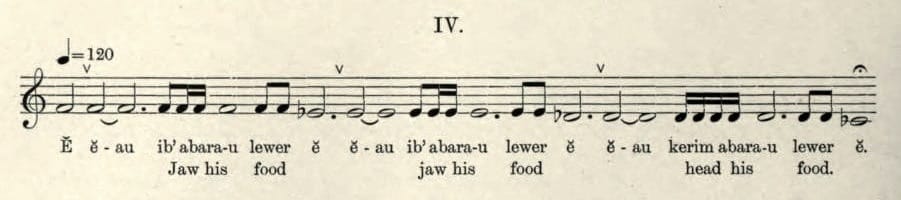

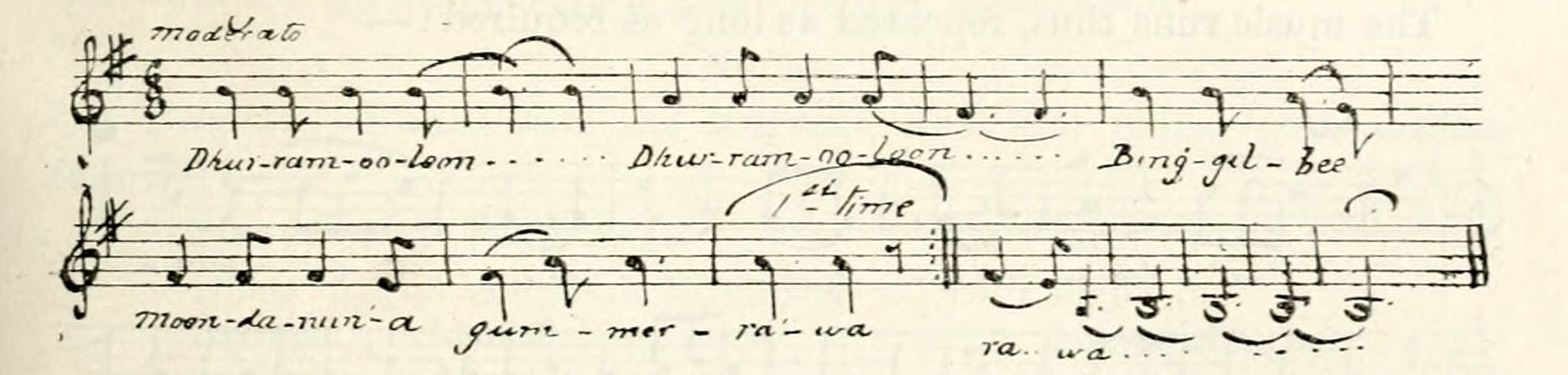

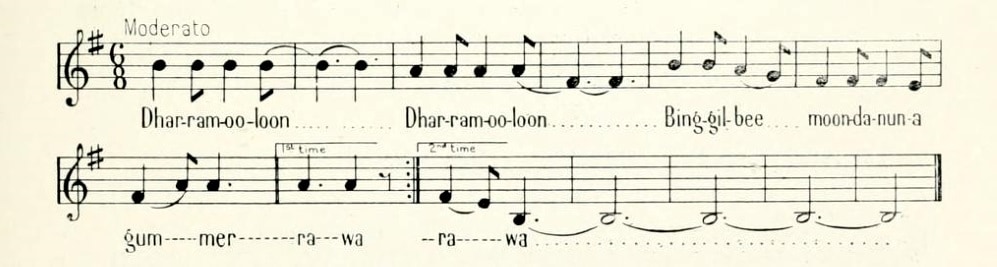

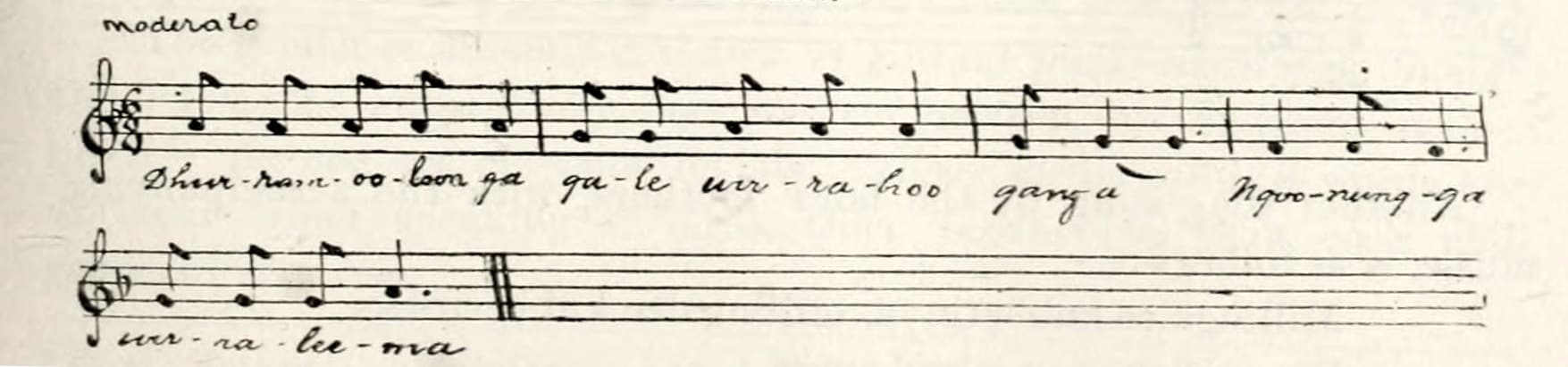

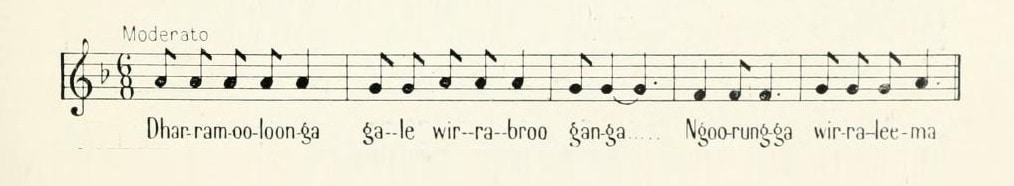

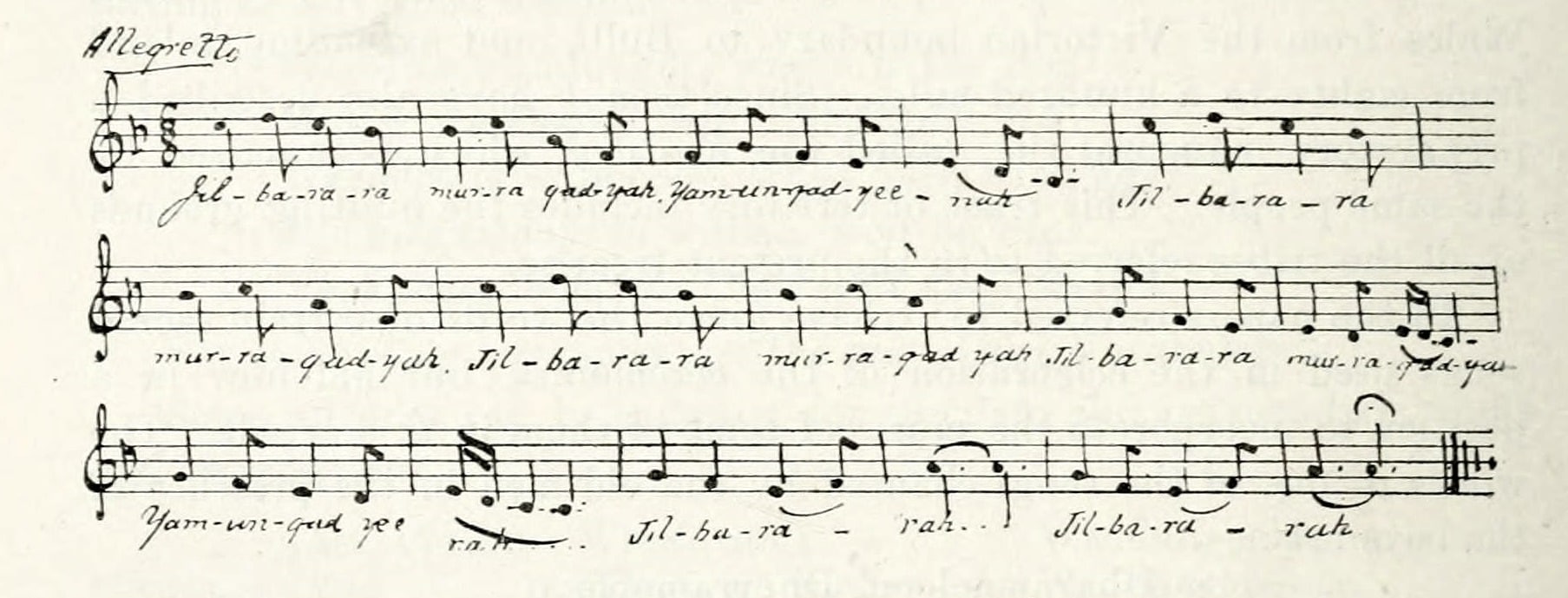

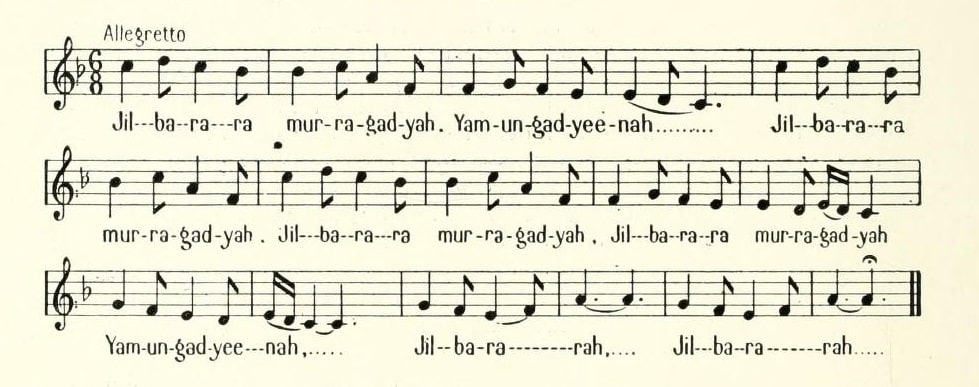

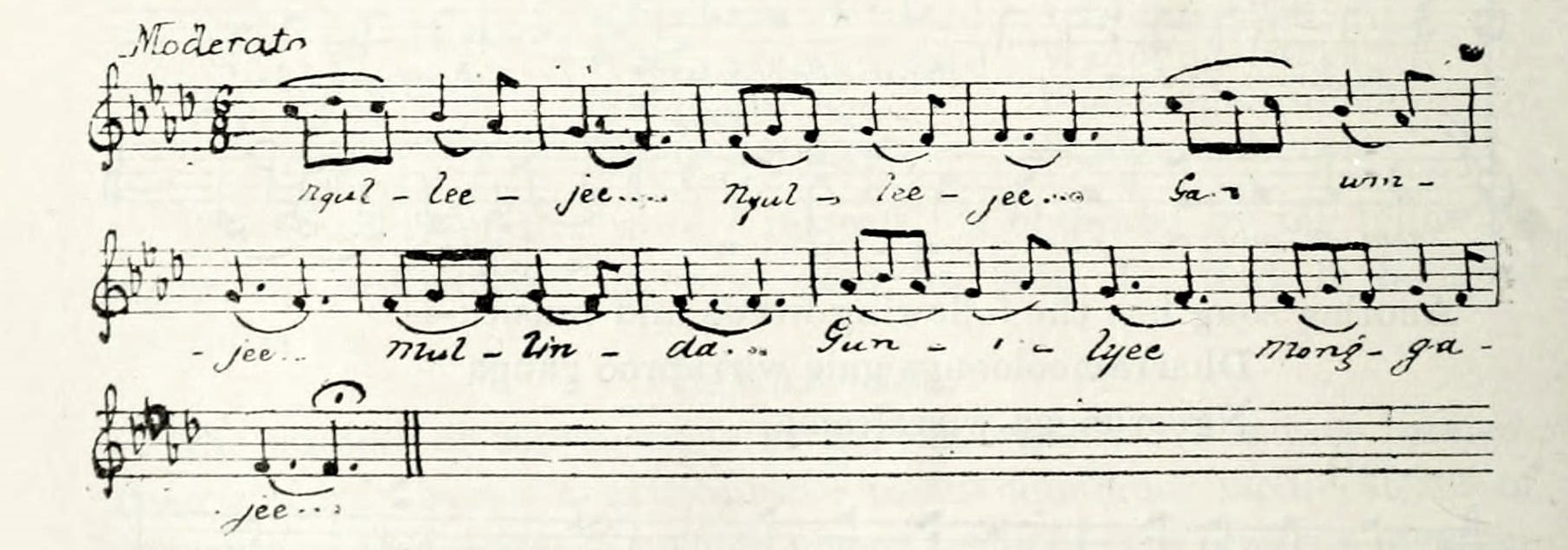

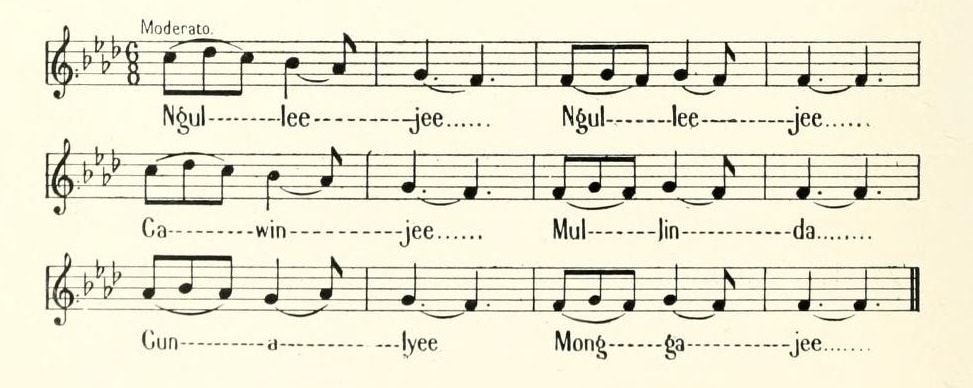

Music and words (no translation) transcribed by Barron Field (1786-1846), from the singing of Harry (c.1787-?), or Corrangie, brother-in-law of Bennelong, between c.1820 and early 1823; first published London, November 1823; second edition London, 1825

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-indigenous-music-1.php#006 (shareable link to this entry)