THIS PAGE FIRST POSTED 14 JUNE 2021

LAST MODIFIED Wednesday 19 March 2025 9:01

Readings in early colonial music

Dr GRAEME SKINNER (University of Sydney)

THIS PAGE IS ALWAYS UNDER CONSTRUCTION

To cite this:

Graeme Skinner (University of Sydney),

"Readings in early colonial music",

Australharmony (an online resource toward the early history of music in colonial Australia):

https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/readings-1.php; accessed 24 February 2026

Contents

On national music:

* Preface (Burney, 1776)

* Music (Nicholson, 1809)

* Of national music (Jones, 1819)

Original Australian content:

* Music a terror (Lang, 1858)

* Reminiscences of the Wallaces (Cox, 1884)

Imported content:

* Musical scenes in Sketches by Boz (Dickens and Cruikshank, 1833-39)

* The old governess and the dreamer of dreams (Thackeray and Doyle, 1854)

* Some journalistic refelections

On national music

A literary party at Joshua Reynolds', hand coloured engraving [after James Doyle]

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JoshuaReynoldsParty.jpg (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: Samuel Johnson, left front, talking to Edmund Burke, with James Boswell (behind, left), Joshua Reynolds, with ear trumpet, David Garrick, Pasquale Paoli, and Charles Burney, sitting and listening; Joseph Warton sitting at the end of the table to right, whispering something to Oliver Goldsmith; Reynolds's servant and heir, Francis Barber, standing at back

Preface . . . (Burney, 1776)

A general history of music, from the earliest ages to the present period, to which is prefixed, A dissertation on the music of the ancients, by Charles Burney, Mus.D, F.R.S., volumes the first (London: Printed for the author, 1776), [vii]

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=XgxDAAAAcAAJ&lpg=PR7 (DIGITISED)

The feeble beginnings of whatever afterwards becomes great, are interesting to mankind. To artists, therefore, and to real lovers of art, nothing relative to the object of their pleasure or employment is indifferent.

The love of lengthened tones and modulated sounds, different from those of speech, and regulated by a stated measure, seems a passion implanted in human nature throughout the globe; for we hear of no people, however wild and savage in other particulars, who have not music of some kind or other, with which we may suppose them to be greatly delighted, by their constant use of it upon occasions the most opposite: in the temple, and the theatre; at funerals, and at weddings; to tire dignity and solemnity to festivals, and to excite mirth, chearfulness, and activity, in the frolicsome dance. Music, indeed, like vegetation, flourishes differently in different climates; and in proportion to the culture and encouragement it receives; yet, to love such music as our ears are accustomed to, is an instinct so generally subsisting in our nature, that it appears less wonderful it should have been in the highest estimation at all times, and in every place, than that it should hitherto never have had its progressive improvements and revolutions deduced through a regular history, by any English writer . . .

Music (Nicholson, 1809)

"MUSIC", The British encyclopedia: or, dictionary of arts and sciences . . . by William Nicholson . . . vol. 4., I-N (London: For Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1809), n.p. [626-26]

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=nDYPAQAAIAAJ&pg=PT625 (DIGITISED)

. . . In former times, when music was less understood as a science, than it is at this day, the rules, or rather the licences for accompaniment were very limited, and confined the harmony to such a paucity of permutations, as would, among modern theorists, be considered bald and puerile. We should not tolerate such music; for the habits acquired, by frequently hearing compositions in which every possible change has been introduced, would render the inexpressive, tame, and monotonous accompaniments of those musicians, who were contemporaries with the celebrated Guido, (to whom the art is highly indebted), little more gratifying than a peal on an octave of hells. We are not, however, to suppose, that plain, simple, melodies are beneath the composer's notice, far otherwise, we could quote many little strains, in which every note is attractive, and which, when duly accompanied, give the greatest delight. Perhaps Pleyel's German Hymn may, in that respect, be considered as neat a specimen as could be quoted; in it we have all the suavity of religion, without any of the dull, tedious, or tautological circumstances which characterize a large portion of church music. The variations annexed to that pleasing air, are proofs of the composer's taste; while the presto which follows, and is upon the same subject as the hymn, given a most agreeable, termination, and is so managed as completely to change the character of the music.

The art of composition requires great genius, taste, judgment, a fine ear, and the utmost patience! without these, good music will never be produced. We should, at the same moment, studiously avoid that pedantic bias, too often received by men of the first abilities, whereby a certain stiffness, and deficiency of air, are sure to follow; few, indeed, have the happy gift of acquiring all the necessary attainments in the theory, and to preserve a pure taste for those lyric compositions which are so highly relished by the multitude. We have, however, seen a Rosina start from the brain of science! Yet, after all, it is frequently with some, difficulty that the favourite airs of other nations gain admittance among us. With persons who can appreciate merit, and who can discover beauty, even among features which may not be very regular, foreign compositions are well received; but it appears to us, that the English (speaking of the multitude) have nearly as much partiality for a peculiar stile, such as the ballads of Dibdin, as the Scots have for their reels, strathspeys, &c. In fact, almost all music may be considered as national; for in every country we find either a peculiar measure, a peculiar mode of accenting, a peculiar kind of expression, or some one or more peculiar circumstances, which at once give a designation to the composition. The Irish nine-eighths; the Scots reversed punctuation; the accent of the Polacca on a part of the bar we seldom, or never accent; the great simplicity of the English ballad; the naivette of the French pastorale; the wild, yet impressive Hindostanee air; the graceful Italian canzonette; the trifling, but cheerful, air Russe; and a variety of others, establish a certain index of national character, at least as conspicuous, and as prevalent, as the features of their various inhabitants.

The notes used in music form a kind of universal language; for, being in general use, they are equally familiar to all civilized nations; hence it is not uncommon to see several persons, who can barely make themselves understood by speech, unite in a concert, and proceed in their several parts with surprising facility and precision. The Italians for a long time had the lead in this fascinating science; and, such was the rage for the compositions of Italian masters, that an immense quantity of music, composed by the professors of other countries, was ushered into the world with Italian indications; by which means they obtained a welcome, and sometimes a celebrity, that would probably have been denied them, had their origin been discovered. These circumstances occasioned the general use of Italian terms; which, in lieu of diminishing since other countries have been able to boast of their justly praised authors, appear to be even more prevalent than ever. The confirmed establishment of an Italian opera, at every great city, in the most polished countries of Europe, seems to have generated a gout, or a partiality for both the language and the representations of Italy. This has given rise also to many deceptions, particularly to the assumption of Italian names by the natives even of England. Such is the effect of opinion, that merit is sometimes obliged to disown her native soil . . .

ASSOCIATIONS: William Nicholson (editor)

MUSIC: On the earliest documented performance of "Pleyel's German hymn" in Australia, see Laying the foundation stone of Henrietta Villa (Point Piper) in 1816

Of national music (Jones, 1819)

[Griffith Jones], Encyclopaedia Londinensis, vol. 16 (1819), 315-16

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=z6XHGGuzduAC&pg=PA315 (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=LwNQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA315 (DIGITISED)

OF NATIONAL MUSIC

Smollet in his History of the Hebrides, tells us, that every laird entertains a piper as one of his household, who always marches at the head of the clan, with his bagpipe, to animate them to battle, with martial tunes composed for that purpose; and that such is the influence of this single instrument over these people, that the piper, by varying his airs, never fails to melt them into sorrow or despondence, and by a sudden transition of rousing them to rage and revenge, and a total contempt of danger and of death; nay even in the greatest emergency of war they will not march a furlong or draw a sword, without being roused by the music of this instrument. The highlanders have a particular species of tune, called a pibroch; some of their tunes (which a stranger cannot possibly reconcile to his ear) are intended to represent a battle; they begin with a grave movement resembling a march, then gradually quicken into the onset, run off with a noisy confusion and turbulent rapidity, to imitate the conflict and pursuit; after which they swell into a few flourishes of triumphant joy; and close with the wild and slow wailings of a funeral procession. This transports and elevates a highlander; it conveys to his mind the sublime ideas of danger, courage, armies, and military service.

There is a dance in Swisserland, which the young shepherds perform to a tune, played on a sort of bagpipe, called the ranz des vaches; it is wild, and has little to recommend it, if we judge only by the notes, without being acquainted with the style and manner of it. But the Swiss are so intoxicated with this tune, that, when abroad in foreign service, if they hear it, they burst into tears, and often fall sick, and even die of a passionate desire to visit their native country; for which reason, in some armies where they serve, the playing of it is prohibited. This tune, the attendant of their early youth, recalls to their memory those days of liberty and peace, those nights of festivity, those tender passions, which formerly endeared them to their country; and awakens in them such regret, when they compare their former happiness with the scenes of tumult they are engaged in, and the servitude they are obliged to undergo, as entirely overpowers them.

Mr. Bruce, in his description of the war-trumpet used in Abyssinia, says that it sounds only one note, in a loud, hoarse, and terrible, tone; that it is played slow, when on a march, or before an enemy appears in sight; but afterwards it is repeated very quick, and with great violence; and has the effect upon the Abyssinian soldiers of transporting them absolutely to fury and madness, and of making them so regardless of life, as to throw themselves into the midst of the enemy, which they do with great gallantry. He adds, that he has often, in time of peace, tried what effect this change would have upon them; and found that none who heard it could continue seated, but that all rose up, and continued the whole time in motion.

Music is in a great measure under the continual influence of memory; that is to say, our pleasure arises not merely from quietly listening to the notes, but from our associating the sounds of those notes with events that have happened long before. This may probably be the reason why a new piece of music, however we may afterwards do justice to its beauty, will seldom make so strong an impression upon us as an old one; and why, in every country, the favourite and real national music will for ever be observed to have a different style from what it is found to have in another country. Music, thus being an accompaniment to our feelings and actions, will therefore display sounds analogous to them, and consequently we shall prefer not only the national tune, but even that tune if sung in our own perhaps ruder language, to the sweetest foreign one. However finer the last may be than our own, however more melodious the sounds may really be than those of the songs of our ancestors, or of our own living national composers, we shall, perhaps, in listening to their finer melody, luxuriously spend our hour, but feel nothing of that warmth with which we are inspired at hearing one of our own national airs sung or played, particularly when unexpected. And thus that national music, viz. those sounds which express the character of a nation, will never be entirely fettered by general rules of beauty.

The voluptuousness of Italian national music will paint a life chiefly spent in pleasure and enjoyment under the most beautiful sky in the world. Next to it comes the national music of the Portuguese, more like the Italian than any other, exhibiting a nation, where, in the want of genius for invention, an astonishing talent for imitation, and a taste in the choice of what they hear and see, has become in itself a kind of interesting originality. Spanish songs bear a resemblance to both; but they possess more energy, united to a romantic turn, and to a certain pompousness.

The national music of all northern nations has in general a melancholy cast, appropriate to a cold climate, connected with a solitary life; yet there will be found some striking differences by which the several nations are characterised. The national songs of the Russians will be easily distinguished both from the Irish or Scottish, or from the Danish or Swedish. There is in their melody very often a sort of barbarism, as the song generally does not finish in the key-note, a peculiarity which is much less observed in the tunes of the other northern nations. To hear a regiment of Cossacks sing, on entering a town, is like listening to the elaborate chorusses on the stage. Whoever knows how difficult it is, sometimes, to make a chorus go on well, even when executed by those whose profession it is, must be struck when he hears common soldiers perform with the greatest accuracy. Whether this talent for music is inherent in the Cossacks, or whether it has been the fruit of study propagated through many centuries, remains doubtful. With this latter supposition we might perhaps look upon it as being derived from the Grecian canonic song in the churches, in the times of the Christian emperors, when, unlike our choral songs, in which every body uniformly sings only the melody, the fingers executed the different parts according to what they thought agreed with their voice; a custom which in still kept up in the Grecian liturgy. The imperial horn music, where from fifty to sixty people play upon the horn, and where each of them, having but one note to sound, yet falls in always exactly at the given time, and so contributes to the performance of a most beautiful concert, is another instance of musical talent which no other country affords.

The great softness of the Swedish, and particularly the Danish, language, makes the songs of those two nations appear less striking than would be the case if we could hear the music set to words of perhaps ruder language. A language may be soft without being agreeable, and may sometimes want the force of the neighbouring idiom without possessing the luxuriant and voluptuous harmony of words of that of another more southern nation.

Very characteristic, and seemingly like each other, yet different, are Scottish and Irish songs: though both are melancholy and gloomy, and though both of them paint the discomforts of solitude, and of a northern climate, yet there is in the Irish tunes more variety than in the Scottish.

England may perhaps be said not to possess any national music at all. There are, no doubt, songs; yet it would be very difficult to recognise by them the character of the nation. To find out the cause of this singular phenomenon, in such a celebrated and great nation, will prove an interesting enquiry. Baron Arnim reasons upon it as follows: If by national music we are to understand the expression of national character, the word character can naturally not be understood otherwise than the representation of the reigning propensities of such a nation in conjunction with the climate in which it lives, and with [316] its moral and political situation, which have operated either in suppressing or in encouraging these propensities. But we believe it would be difficult to point out any other propensities of the generality of the English nation than the love of virtue, country, and domestic happiness, every effusion of enthusiasm being already suppressed as well by religion and education as by habit. These propensities of the mind, united to a mild climate and to a happy and glorious constitution, will therefore make the songs of the English appear gay, although not very lively; and therefore pleasing, without producing a deep and lasting impression.

But, allowing the English to have strong passions, there exists another reason which explains the absence of national music in them; that is, they have no leisure to exhale their character in songs. The national song has always been the offspring either of solitude, and of activity (if mind and feelings, without the means of applying it to action, or of a voluptuous doing nothing - the dolce far niente of the southern nations, the effect of a hot climate, which, joined to an ardent imagination, invite us either to the enjoyment of repose, or to the gratification of the senses. The difference between the stanzas of a song and the verses of many an epic or didactic poem is therefore almost the same as that between a national melody and a great musical composition, in which harmony is often found superior to melody. A genuine national song is, as well in words as in melody, the produce of imagination. A poet, who in such a moment is conscious of the rules of poetry, a musical composer who remembers those of music, will never produce any thing that may please the whole nation, whatever be the occupation in which individuals are engaged. The most national song that ever has been generally sung throughout a country is the German air, Freut euch des lebens, "Life let us cherish." The composer (his name is Nageli) is only known as the author of some learned music, which perhaps will one day be forgotten; but his song will last for ever, as well as our famous air of "God save the king."

In the southern climates, the youth sits in the evening before his door; the heat of the day is over, the air is tranquil, no idea of rain or storm, the sun is setting with a glow, the sky produces a finer blue than anywhere else; he is perhaps awaiting the fair one who will bless him with love, or is retracing past happiness. What reason for inspiration of rapturous ideas! Words and music come almost together. Who can think of a rule, or count the syllables on his fingers? and yet the song is enchanting. If the northern nations do not see their sun so glowing, if their sky has not the same blue, and if the plants do not exhale the same fragrance in their country, yet not less does the want of all this inspire the poet and the composer, and produce familiar effects, although the style of the compositions will be found very different. It is therefore not always what nations enjoy, but very often a consciousness of the privation, which produces their songs; and it is this which accounts for the melancholy and gloomy cast of most of them. The most fertile inspirer of songs is Solitude. Among all mountainous countries there will of course be found specimens of national music; and, from the times of old until ours, the shepherds have not only invented songs, but their occupations have even supplied the theme of many a musical composition.

It is for these reasons that any free and at the same time commercial nation, where, every-body, during the day, is either involved in the bustle of his own or of the affairs of the community, and where, in the evening, the great interests of the state absorb people's minds, and are discussed, will not have many national songs; and this is particularly the case with the English, where, by the care of the welfare of the community, and the constant endeavours to keep up a free and glorious constitution, man is almost constantly attracted, from his earliest youth till the last days of his existence in this world.

Biographical note on the author (by Graeme Skinner, 2019-21)

Griffith Jones was born in Soho, London, on 6 August 1757, a younger son of Griffith Jones (1722-1786), printer and bookseller, a freeman of the Stationers Company, and Jane Gilles (b. 1724). His uncle Giles Jones (1716-1799) was the father of the author Stephen Jones (1767-1827).

He entered St. Paul's School, aged 12, on 18 July 1770, at which time the address of his father's printing business was given as 7 Bolt Court (an elder brother, Lewis, was already at the school).

Jones was recommended for membership of the Royal Society of Musicians on 7 March 1779, at which time he was described as being 21 years of age, single [sic], having served his musical apprenticeship under Charles Frederick Baumgarten, recently employed at Covent Garden Theatre (for the winter season) and Haymarket Theatre, and proficient on the violin, clarinet, organ, "etc." In 1784, if not earlier, he was pianist at Covent Garden, where, according to his friend (and fellow Baumgarten pupil) W. T. Parke, he taught the vocalist Charles Bannister, who could not read music, his songs by rote. He was probably the G. Jones who played tenor (viola) at the Handel Memorial Concerts at Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon in May and June 1784.

On 6 October 1787, at St. Bride's, Fleet Street, the marriage took place of "Mr. Griffith Jones, of the orchestra at Covent-garden Theatre, to Miss Laidlaw". Minute books of the Royal Society of Musicians list Jones as playing tenor (viola) at St. Paul's Concerts on 10 and 12 May 1792, and again in 1793, 1794, and 1795. On 2 July 1797 Jones explained that he had missed a recent Whitehall concert due to illness. A G. Jones was an instrumentalist at the Covent Garden oratorios in 1789, 1799, and 1800. He published an elementary keyboard tutor, The complete instructor for the harpsichord or piano forte, c. 1789, which was reissued in a new edition by George Goulding, c. 1800.

By late 1812, and possibly earlier, Jones had re-established himself as a bookseller and publisher at 17 Ave Maria Lane, near St. Paul's. This was the address from which the late John Wilkes had advertised and published the early volumes of his Encyclopaedia Londinensis (from c. 1795-97 to 1810). At Wilkes's death in 1810, he left the ongoing management of remaining the volumes of the project to his "managing editor" Joseph Jones (1762-1838), Griffith's younger brother. Joseph appears to have continued the project at least to the end of volume 22, and "G. Jones" was named as publisher of the last two volumes, 23 and 24. Griffith Jones was himself author of the articles on music which appeared anonymously in volume 16 of the encylopedia in 1819, and published separately by him, under his own name, in the same year. A German translation was published in Vienna in 1821.

In 1819-20, Griffith Jones renewed a lease with the Stationers' Company on 17 Ave Maria Lane, and in his will, proved in 1833, he indicated that "a sum be payable from the Stationers company in city of London." He died at his residence in Upper Baker Street, Marylebone, on 23 December 1833, and was buried St. Mary, Paddington Green on 31 December.

Published sources:

"MUSIC. HISTORY OF MUSIC, THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL", Encyclopaedia Londinensis . . . vol. 16, containing a comprehensive treatise on music . . . (London: Printed for the proprietor, at the Encyclopaedia Office, 17, Ave Maria Lane, 1819), 285-400

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=z6XHGGuzduAC&pg=PA285 (DIGITISED)

History of the rise and progress of music, theoretical and practical by G. Jones, extracted from the Encylopaedia Londinensis (London: [Jas. Adlard] For G. Jones, 1818) [offprint of the above, same pagination]

http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10513F71 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=D_lOWjIuMacC (DIGITISED)

[Review], The new monthly magazine (1 October 1818), 243-245

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=-dYRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA243 (DIGITISED)

. . . Mr. Jones was, we believe, a pupil of the venerable C. F. Baumgarten, now the last remaining of the old school . . .

[concluded] (1 December 1818), 446-48

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=-dYRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA446 (DIGITISED)

Also mentioned [Review], The new monthly magazine (1 February 1819), 62

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VCQ8AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA62 (DIGITISED)

Geschichte der Tonkunst von G. Jones. Aus dem Englischen übers. und mit Anmerfungen begleitet von J. F. Elden von Mosel (Vienna: Steiner und Comp., 1821)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=E4-5tHjBhpwC&pg=PP7 (DIGITISED)

[Review], Conversationsblatt. Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche Unterhaltung 1/3 (10 January 1821), [literary supplement] 1

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=_hgYgp_FiBoC&pg=PA36-IA1 (DIGITISED)

Musical works:

The complete instructor for the harpsichord or piano forte, wherein the fundamental principles of these instruments are fully explained, the proper mode of fingering illustrated by a variety of examples consisting of some of the most favorite airs, together with a collection of progressive lessons, selected from some of the best anthems, & some original pieces never before published by G. Jones (London: W. Campbell, [1786])

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=OoogEtIPRGoC (DIGITISED)

[Later edition of the above, by George Goulding, c. 1801]

On acquisition, see “MUSIC”, British Museum quarterly 29/1 (1965), 54

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.533633/page/n69 (DIGITISED)

Bibliography and resources:

"MARRIAGES", The gentleman's magazine (October 1787), 934

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=TqZJAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA934 (DIGITISED)

MARRIED . . . 6 [October] Mr. Griffith Jones, of the orchestra at Covent-garden Theatre, to Miss Laidlaw.

W. T. Parke, Musical memoirs; an account of the general state of music in England from the first commemoration of Handel, in 1784, to the year 1830 . . . (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830), 32

https://archive.org/stream/musicalmemoirsv100park#page/32/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

[Shield's Robin Hood, opened 17 March 1784] . . . It is a curious fact, that Mr. Bannister, who never sang out of time or out of tune, did not know one note of music. He had his songs, &c. paroted to him by a worthy friend of mine, Mr. Griffith Jones, who was at that time pianist to Covent Garden Theatre . . .

"George Jones" [sic], in Friedrich W. Ebeling, England's Geschichtschreiber von der frühesten bis auf unsere Zeit (Berlin: Herbig, 1852), 107

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=giUIRvko2q4C&pg=PA107 (DIGITISED)

Charles Knight, Shadows of the old booksellers (London: Bell and Daldy, 1865), 236, 241 [on Griffith Jones senior]

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=Y0Y5AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA236 (DIGITISED)

The admission registers of St. Paul's School (London: George Bell and Sons, 1884), 148

https://archive.org/details/admissionregiste00stpa/page/148 (DIGITISED)

Admitted 1770 July 18 / Griffith Jones, age 12, son of Griffith J., printer, at No. 7 Bolt Court [Also elder brother Lewis Jones at the school]

Charles Walsh, A bookseller of the last century: being some account of the life of John Newbery, and of the books he published, with a notice of the later Newberys (London: Printed for Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh, successors to Newbery & Harris; 1885), 44-46 [on Griffith Jones senior]

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044014490668;view=1up;seq=64 (DIGITISED)

Charles Henry Timperley, The dictionary of printers and printing, with the progress of literature (London: H. Johnson, 1839), 759-60

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=UmxTMABJ9q4C&pg=PA759 (DIGITISED)

"Jones, George" [sic], in Brown and Stratton, British musical biography . . . (Birmingham: S. S. Stratton, 1897), 223

https://archive.org/details/britishmusicalbi00brow/page/223 (DIGITISED)

Theodore Baker (ed.), The biographical dictionary of musicians (New York: G. Schirmer, 1900), 300

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t7cr6d15t;view=1up;seq=314 (DIGITISED)

William ApMadoc, "MUSIC NOTES" The Cambrian: a monthly magazine 21 (1901), 310

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433074924113;view=1up;seq=318 (DIGITISED)

Philip H. Highfill, Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans, A biographical dictionary of actors, actresses, musicians, dancers, managers, and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800, volumes 8: Hough to Keyse (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1982), 234

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015052092999;view=1up;seq=246 (DIGITISED)

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=mjeImcc9rGwC&pg=PA234 (PREVIEW)

Donovan Dawe, Organists of the City of London, 1666-1850: a record of one thousand organists with an annotated index ([Purley]: D. Dawe , 1983), 23, 116

Other references:

Baumgarten:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Frederick_Baumgarten

Wilkes:

Bernard Adams, London illustrated, 1604-1851: a survey and index of topographical books and their plates (London : Library Association, 1983), passim (Jones), 261 (Wilkes)

[261] John Wilkes was a printer of Winchester who had set up as a London bookseller and stationer at 17 Ave Maria Lane in 1790, became a liveryman of the Stationers' Company, prospered and bought himself a house in the country . . . His chief undertaking was the Encyclopaedia Londinensis and it was in connection with this publication that, in 1808, he was fined £100 for pirating material belonging to a fellow publisher named Roworth . . .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wilkes_(printer)

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Jones,_Stephen_(DNB00)

Encyclopaedia Londinensis 1-24 (Wilkes 1797-1810; Jones 1810-29)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001464690

Walk through Sydney in 1828

![Plan of the town and suburbs of Sydney, August, 1822 ([?: ?, 1822])](imageslocal/sydney-town-and-suburbs-1822.jpg)

Plan of the town and suburbs of Sydney, August, 1822 ([?: ?, 1822])

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229911701 (DIGITISED)

Walk through Sydney in 1828

"Walk through Sydney in 1828", The South-Asian register (1 December 1828), 319-31

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/232925889

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-608525450/view?sectionId=nla.obj-633692285 (DIGITISED)

ARTICLE III. Walk through Sydney in 1828.

THIS is an Editorial precession, or to speak with more dignity, a progress, on which we shall set out from the King's Wharf, Sydney Cove. The sun is just rising, glancing through the trees on the opposite side of the water, and in spite of their dark evergreen foliage, giving something of a grassy hue to the lawn in front; but it can scarcely be called green with the best light. That long verandah cottage on the side of the lawn, with a hall growing out of it, like the genteel seat of a very modern country gentleman in England, is the residence of the representative of monarchy. Edifices, of every description, are an image of the times and of the manners of the founders. They are like the apparel "which oft betrays the man" - How sweet is the air of the morning, so cool and fresh and wholesome! It is a thousand pities that so few people experience the pleasure of rising early; a practice so conducive to health, long life, and riches. An early riser seizes Time by the forelock, and stands apart as it were for the race of life, ready when it begins, to take every advantage, having his thoughts cool and duly arranged, before there is any noise or bustle to confuse him. Yet here are the shops of Sydney, a new world of enterprise, all closed, to remain so most probably, long after this blessed hour of sun-rise, - except the publicans however, who doubtless therefore have their reward.

Before starting,

"To catch the manners living as they rise," we must take another look at the shipping in the harbour - a goodly sight of masts to be in this distant nook of the earth.

There are no less than eighteen ships, a dozen brigs, and half-a-dozen schooners or maphrodites, as the sailors call them.

This little plantation, will one day become a great forest, no doubt, if there be but a "royal race of men" to watch its progress.

How many living abstracts of the old world have come, and will come, to this port, -

each bearing, like Noahs Ark, the seeds, plants, animals, [320]

the arts, tradition, history, and manners, of that dear unhappy earth,

which the family within saw gradually sink, as did the Patriarch's, beneath the flood, when all thereon, became a dream.

It has often been a matter of wonder to us, looking at the various exiles here, what strange inducements could have brought them to this remote shore.

To float as they have done, for the space of fifteen thousand miles, over the unsteady surface of a fatal element,

with only a plank to hold them, all the while, from dropping down an unfathomable abyss! -

thus traversing a wide region of death, to find a new and uncertain life.

Many thoughts and singular events, tend beforehand to an alternative, so dire to the imagination as this.

Human life, however, is but a picture of a series of shadows, formed by our varying sentiments, appetites, and passions,

the necessary origin and termination of which, is to us unaccountable.

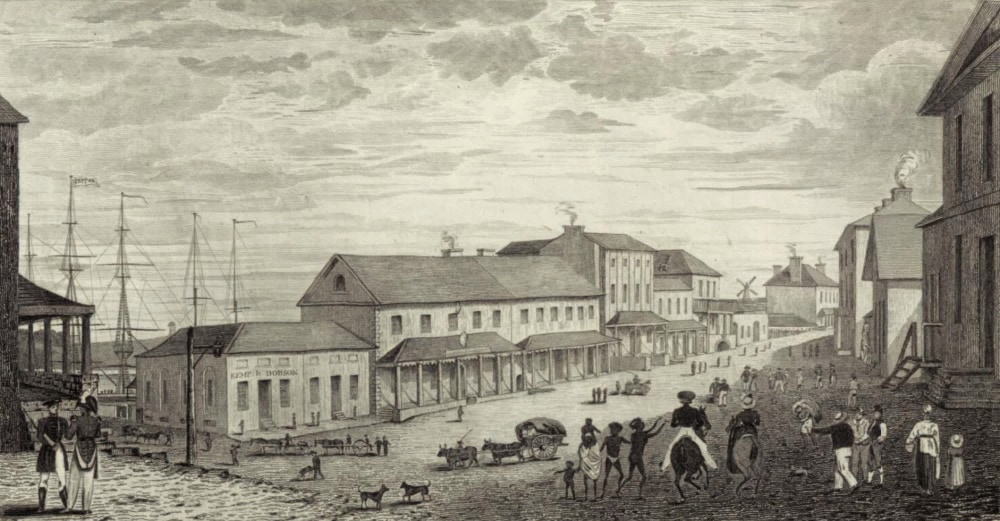

[Detail], A view of the cove and part of Sydney [with Campbell's Wharf], "Engrav'd by W. Preston from an Original Drawing by Capt. Wallis. 46th Reg.t", c. 1818; note, on the horizon at right, the hospital, but the Hyde Park Barracks and St. James's Church are yet to be built.

http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110073319

Here we are still on the King's Wharf, - a wooden landing place partly new and partly old, altogether large enough, to unload one ship at a time, with small craft. On our right are the Commissariat Stores, two warehouses four stories high, built of stone, tinted by the weather as if they had stood for centuries, instead of scarcely twenty years. Entering George Street, the stranger's eye is invited to the Indian Arms; the mariner's, to the Three Jolly Sailers, who join in the following apostrophe to his good nature:

"Brother Sailor please to stop

Lend's a hand to strope this block."

George-street from the wharf [in the Rocks, with the Australian Hotel] drawn and engraved by J. Carmichael, 1829; National Library of Australia

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-134348824 (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: John Carmichael (artist, engraver)

Close by is the Duke of Wellington and the sign of The World turned upside down; the reality of which position is demonstrated, to those who enter, by Master Ticklebrain and his usher ready anon Francis. Leaving these and other symbols of renovation, which are alike cheering to the traveller, we turn our face southward and pass on George Street. Each side presents a respectable line or succession of houses, two and three stories high, built of stone, or brick stuccoed - on our left is the Australian Hotel, and the Chamber of Commerce, so called, which, with several in the same line, have genteel verandahs. On our right is a range of shops, of quite a metropolitan aspect. The first inscription is, Chronometer Maker, the second, Wine Merchant, formerly Printseller, then Pastry Cook, and Music Warehouse, but should be Gunsmith; the window being darkened with rows of unmusical pipes, full of no one knows how many ghastly forms of death; instead of the gentle Ariels, the delicate invisible ministers of delight which dwelt there before, ready to do the bidding of any potent master. These changes indicate poverty. The picture dealer and the musician started into being before this new city could afford to purchase their luxuries. Yet what is a city without the fine arts? They are [321] its lights, the lamps to our feet, which keep us from stumbling when we pass the dim mansions of empty thoughts and distempered cares.

We are now between two stone edifices of doubtful antiquity, but probably verging on a quarter of a century. One has a stone verandah front with well-wrought ancient Ionic columns and a sort of Tuscan entablature, the whole supported by a large gateway of rustic work with a masqued keystone - This is the first symptom of Architecture in the Gothic Antipodes. The other, nearly opposite, has a species of Ionic pilasters with urns on the top and a pediment supporting a graven image, sculptured in the stiff doughy attitude of a South-Sea-god, only that he bears in his arms a battle-axe of our North Countrie. A lion couchant and an unicorn are by his side - From here we come between the New Zealand timber yard of soft pines, and the old Gaol, so called since the talk of a new one. It is old albeit, and subject to imminent dilapidation; they say it was built by a shoemaker, and we might add ne sutor ultra - but it is an ill wind - as the Governor of Barrataria would reply. Eight or ten score of misgiven souls are commonly immured here, and a number of them, as seen in Mirza's vision, pass through trap-doors leading to Pluto's region or the land of Cimmeria. On our left is a range of neat brick houses, the first of which is the Australian Bank, having a massive Tuscan portico, the columns without bases and also without pilasters, which is not according to Hoyle, we conceive. The strong vault of this bank, containing all its treasures, bonds, and monies, was recently entered by thieves who deliberately took away, it is said, between ten and fifteen thousand pounds, of which catastrophe there is yet no denouement. On our right is a blank space, and next it the first story of a once intended theatre. Adjoining it is the Sydney Gazette Office, from whence that industrious official journal issues three times per week, costing the subscribers to it six pounds a year. Some little time ago, it was published daily, but this proved a stroke beyond the mark. As philosophers, our business in the street, is to utter wisdom or say nothing, we therefore bid good morning to the Editor, as we would to the player, were he neighbour, believing what Hamlet says of the latter is also true of the former. "After your death you were better have a bad epitaph, than their ill report while you live."

Edward Charles Close, St. Philip's Church Sydney, c. 1817; State Library of New South Wales

http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110339254

http://digital.sl.nsw.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL3271524 (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: Edward Charles Close (artist)

Here we come to the foot of Church Hill, and looking up, see several snug family houses, a windmill, a green, and the humble stone edifice of St. Philip's Church. On the left at the corner, is the Lumber-yard, full of work-shops and stores, where Crown mechanics help to build and decorate this new city. On each side of it, shops are built and building of stone, chased or rusticated, in a style of neatness and elegance, scarcely to be expected on the borders of a savage wood. But so it is, civi-[322] -lized man is a species of magician, commanding the elements and the vasty deep. Is it better to be a magician? Prospero was of the true order, yet held it only as an instrument.

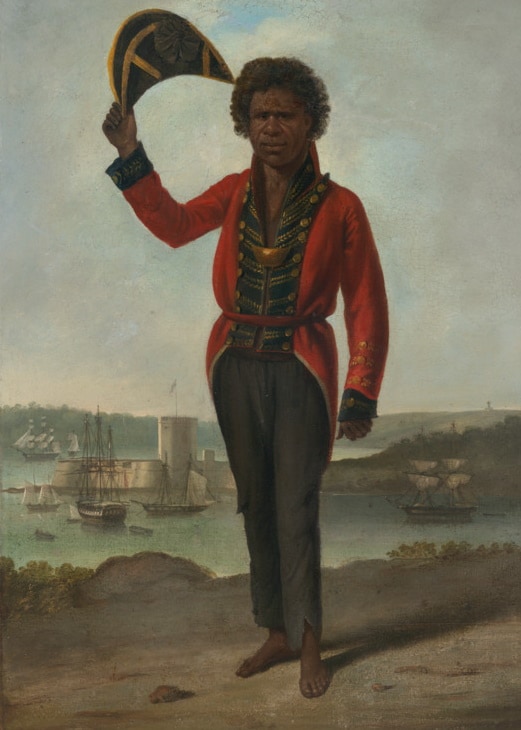

Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales, by Augustus Earle, c. 1826; National Gallery of Australia

https://searchthecollection.nga.gov.au/object?uniqueId=62242 (DIGITISED)

Who come here? A troop of blacks walking to the military band to feed their ears with the music. These unsophisticate beings have no conjuring book, but are alike bare and unfurnished as the four-footed prowlers of the wilderness. Bungaree is at the head, with his military cocked hat on, tipped with invariable politeness to every gentleman - Good morning Sir, how are you? "Quite well Bungaree, thank you." Can you lend me one dump, Sir? - Master! I tay Sir, you know me? have you got any coppers? "What's your name?" Dismal, Sir. I come from the Coal Ribber you know. "Aye, Aye, Sydney's a finer place than Newcastle?" O yes Sir, finer, murry finer, tausend houses, murry tausend tausend houses. Have you seben pence hapenny Sir? lend me one dump - coppers master - buy a loaf you know - look at my belly - murry hungry Sir!

Fine shops on each side; general warehouses of every known manufacture, whether of China or London, the island# of the South-Seas, or the continents of both hemispheres. Every thing is sold here except, as the sages of Greece would say, virtue and wisdom; but the latter is, sometimes sold, dear enough, when the article is rare. The Australian Newspaper Office. This paper has sold 600 copies twice per week it is said, and the copy-right was recently disposed of for at £3,600 to eight share-holders, by Dr. Wardell. A proof that in New South Wales there is a monied or a reading public.

We now come to the long blank wall inclosing the Military Barracks, which are equal to the barracks of any provincial town in England, though rather showy than substantial - opposite are several neat detached houses, and the Bank of New South Wales, the share-holders of which, till lately, realised 40 per cent. on their shares.

What a whirlpool of dust! Huff, sand-blind - quite a tornado - passed in a moment - but to be in it half a moment, is enough. We must step to Mr. Saleure, and interrogate him as to the probabilities of a new coat. Mr. S. was born to be a courtier of the first limpidity, but for Anthropos, or the fatal shears. "Good morning Mr. S?" Your servant Sir. "When can we have the coat ordered six weeks ago which was to be done instanter?" Why Sir I'm very sorry to disappoint you, but it's in hand Sir; I think it's done; I'm nearly certain it is - but Jerry, run and see, and let me have it if it is. Beg your pardon Sir, will you condescend to take a chair, I am informed that the ship just come in, brings late English news. Hem! Eh? - I am very sorry, quite ashamed indeed, but your coat shall be finished by to-morrow evening - or, the end of the week at farthest. "Pray do not fail then, Mr. S." No Sir, you may rely upon me, and I'm very much [323] obliged for your indulgence so long - but the coat Sir shall be a beautiful coat, the cloth is like silk, soft as velvet. I'm sure it will give you satisfaction , a very handsome -

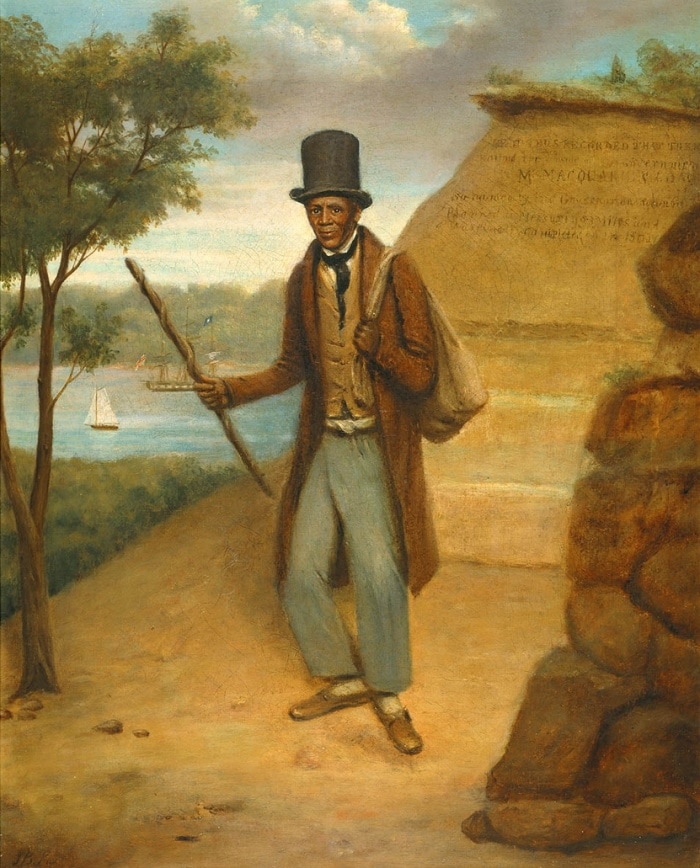

Billy Blue, at Mrs. Macquarie's chair on Farm Cove; by John B. East, 1834; State Library of New South Wales

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Blue#/media/File:BillyBlue.jpg (DIGITISED)

Ha! ha! ha! All my people - Old Standard for ever! Commodore for ever! What sable Democritus is this, holding his side in a fit of laughter? Billy Blue, how do you do? Go home child and learn your book, there's a good child. Good morning William? Good morning your Honor, - morning Sir, I hope your Honor's well and all the family at home? - I've seen the day. A-hem! Young woman there, - go on, go on. Let the ladies pass. Ha! ha! ha! Colours! Colours! Standard for ever! The Commodore for ever! never strike!

This old man deserves a pension. From one end of the street to the other, scarcely a day passes but Billy Blue, an Octogenarian, a poor American black, makes more than half the faces he meets look happier. Many a one smiles or laughs at him, and at nothing else. Mirth is the proper effervescence of life, but sadness is a gloomy vice, or a disease, destructive to soul and body. Here comes the military band in their gay uniforms. What a pleasing buoyancy is given to the air. We step lighter, feel nothing but music, and are tempted to join in the martial tune.

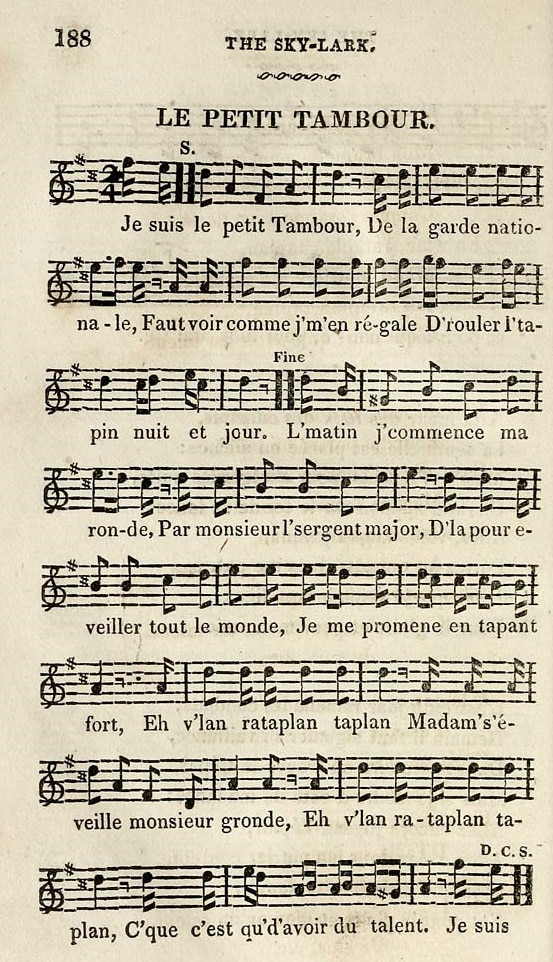

Tune for "With helmet on his brow", "Le petit tambour", from The sky-lark, a collection of songs set to music (London: Thos. Tegg, 1825), 188

https://digital.nls.uk/special-collections-of-printed-music/archive/87683584 (DIGITISED)

"With helmet on his brow, and sabre on his thigh,

The Soldier mounts his gallant steed to conquer or to die!

Then let the trumpet's blast, to the brazen drum reply,

A soldier must with honor live or at once with honor die!"

We now pass a few houses in succession and several detached structures sufficiently genteel, but somewhat disfigured by a covered gateway, the inseparable concomitant of Sydney architecture. He, who would lay out a new town without back lanes, alleys, squares, areas, and a multitude of footpaths in the suburbs, has no claim to the gratitude of posterity. Sydney is deficient in all these requisites at present, and as it has arisen from a village of wooden huts, by partial improvements, no one bears the blame of what it is. But the populace of a town should always be made comfortable, as a recompense and guarantee for the restrictions of accumulated property.

Passing King Street, where there is a vista of the neat Church of St. James's, we come to a lofty edifice stuccoed, with an unfinished portico supported by square columns, and a scroll pediment above like the front of a Dutch house, having in the rear a warehouse apparently, four stories high, with a windmill above the roof. This warehouse internally is fitted up as a theatre, and the front as a saloon - but the origin of evil, is not a not a more controversied or doubtful question, it is said, than the propriety of a theatre in our Protean, Harlequinade society.

The town begins to swarm. Fish ho! Fine sand mullet. Snappers all alive. Here's your fine large King-fish, sand mullet, whiting, fish-ho! [324] Oysters ho! all fat. Fat and good oysters ho, all fat, all fat. Hey! What’s the price of your oysters? "Six-pence a pint." Does that pay? "Yes Sir, but there's a deal of trouble to take them out of the shell, and we have to fetch them five or six miles off and perhaps farther." The cries of Sydney are all genuine cockney, perfect in tune from the deep guttural, to the shrill and plaintive cadence. Another is approaching. Fine Banbury cakes and mutton pies, all hot, all piping hot, all hot and smoking, all piping hot. This fellow was at one time a banker and bill broker to a large amount, in dollar notes and quarter dollars, but riches have wings, and grandeur as the poet says, "is a dream; the man we celebrate must find a tomb."

Siste viator! that is to say stop! What cry is yond, like the rattling of a turkey-cock? We have heard it for years, and often tried to catch an odd syllable of interpretation, but were invariably baffled, though we have a school of tongues in our stomach. Good man! (filthy rather too) pray what have you for sale? "Caul, bullock-head, and bullock-pluck." Hem! Beside these cries, there are others changing with the seasons, as oranges, peaches, melons, lemons, pumpkins, &c., milk at 8d. per quart, 30 per cent under proof; the proof is perhaps too strong for most constitutions in this climate, though to say a land flowing with milk and honey, conveys a fine luxurious image of its richness and fatness. Here is the Waterloo Warehouse, an extensive brick building five stories high. The market place is opposite, and as it is market-day we will pass through it. On the outside of the gateway, amongst other small adventurers too needy to pay for a stand within the fence, we observe one of the trade, a vendor of literature. "What are these books about?" Some very good books Sir; there's the history of Theodore Goodchild, and some beautiful tracs with cuts, and a volume of true prayer, and the trial of Jonathan Wild, Newgate Calendar, Ready Reckoner, and Hamilton Moore, a little soiled.

This market is like a village fair. On the left we see maize and wheat for sale; on the right, green forage, pumpkins, melons, cabbages, turkies, ducks, geese, sucking pigs, fowls, &.; in front are rows of booths full of drapery and grocery; then there are pots, pans, and butter 3s. per lb., and potatoes 15s. per cwt. These girls with butter are somewhat sallow and sun-freckled, have sharp chins, wide foreheads, flat faces, and are of majestic stature - natives, evidently. What a powerful effect the climate must have, to change as it does the contour and mould of our children all at once, without any reason as signed by the chymist. Yet he might write a volume upon this subject very well, and analyse galions of air, tending to prove that it is so. A number of respectable persons, especially of the fair sex, lounge about the market, every Thursday, to [325] diversify the time. At the further end, fronting a public building surmounted with a dome and cupola, which was formerly a market-house and is now a police-office, there stand three several stocks of unusual height; and instead of being grown over or about with grass and brambles, as we have seen such instruments in England, these are in daily occupation. Her the poor and ignorant, who contrary to the laws of physic super-saturate their earthly part, are doomed to a penitential exhibition, unless they pay dowm five shillings for their ransom. Several who deem this too much, embrace the open mortification as a minor evil, and "refuge their shame", as Shakspeare says "by thinking that many have, and others must sit there." The erring sex, are specially subject to this alternative.

The Police-Office and Watch-house contiguous, inclosed by a high brick wall, afford every convenience required. In fact few towns have a more ample police establishment than this, or a more effective one, considering the materiel of which the subordinates are essentially composed. There stands one quavering his staff of office ever [sic, over] a degenerate caitif, more gay than rich, and more merry than sober. Walk, and give me no sauce. - I'm a free man! - Come walk. - I'll walk if I like, or I'll dance if I like, I'm a free man, and, I care for nobody; tal lal de diddle lal!

What company is this, with straw hats on and kangaroo caps, some with shoes and some without, clad in jacket and trowsers. On the latter appendage there is the imprint of a javelin and the initial characters P B. P B. and C. B. They step in rank and file, with a deliberation of movement, unknown to more giddy mortals. An antiquarian, might ponder over the picture of these people for years, without finding their origin or history. We are not able to determine how the Helots of Lacedemonia looked, or the Israelites under Pharaoh, or the twelve thousand Jews who built the Coliseum at Rome, but we suppose they looked something like these men; and if they looked so, it was not very bad, though bad enough. Some have an obdurate scowl about their eyes, and others an innocent twinkling; and others, have a settled expression of either apathy, despair, or resignation. Yet wretches at home think, that loss of freedom is nothing here, that slavery is not slavery! An open letter, dogs-eared and torn, was found in the street a short time back, addressed to one of these friendless men, which shows the misconception of the writer on this point, while it affords an evidence of Irish degradation and Irish attachment, quite national.

My Dear Brother,

I received your letter from Cork and Is happy to think you got there safe but i was greatly fretted

when I herd that the vessel was drive Back but thank god that you all got safe to cork

Dr Edward iam very well at present but [326]

i left the House that i was living in but i got 6 months In Newgate for keeping it and so did every one in the Lane to get the same

Mr Carty went to Est Indias shortly after you went but i expect Him home soon your brother thomas and his wife was in town some time a go

and The sent there Love to you and hopes That it is the best turn that ever happened you with the help of god

and your sister Mary and her husband and Charles sends all their love to you and all their children Is well

I happened to be in newgate the time that i wrote this letter to you & i sent it by a girl that you new yourself that was going in the Transport vessel to bot- [any]

As it was the only convenient way That I could ge for to send it safe to you

for i wrote to you before and never got any answer

My dear brother the girle tha is taking this to you is a particular acquaintance of yours

& I hope that with the help of god that she will find you well

my Dr E you need not be sorry for laving Ireland as indeed it is very badly situated at present

& the are transporting the boys For ever so trifeling a thing

& newgate is full and all the place of Prisomnents to is full.

My Dr brother this is my first of Prison & I hope that it will be the last with the Help of god

Elen Simpson & Maria Jackson & all the girls sends their love to you -

so no more at present but the old Mother sends her love to you

I remain your loving & affectionate sister until Death

FRANCES CARTY

Direct your letter to No 1 Saint Andrew's Lane to Mrs Coil to be forwarded to me

My dear Brother wright to me the first opportunity for god sake as it wood give me a gradale of pleasure

as i said before to hear from you my D brother

For Edwar Bills -

Bot new South

Whales or Elsewher

Close to where we now stand is the foundation of an intended new Cathedral, laid by Macquarie, but abandoned on Mr. Bigge's inquiry. The site is well chosen, being central and elevated. Had this church been proceeded with according to the plan, it would not have been finished before it was wanted, for it is wanted now.

A herd of cattle approaches, leisurely. Well my man, whose cows are these? "Different people's Sir, it's the town-flock, I get 8d. a head a week for taking charge." Some good cows among them, but poor, dreadfully poor. "Yes Sir, some fine frames of cows." And where do you obtain pasture for these twenty or thirty head? "Pasture Sir? Lord bless you, it's very bare of feed where they go. But I take them out early in a morning and they get a snift of fresh air as sun rises, and a drink of fine water, so they pick about like till it's time to [327] come home, and then I water them again!" The cow is known to be a ruminating animal, but "chewing the cud of fancy" is of itself too abstracted.

Amongst the shops and taverns and cottages, which line the outlet of George-street, all more or less common-place it not vulgar, we observe one where Ic. dole has "ta'en the antiquarian trade." Here every human implement used in past generations, or even the present, may be found; and most of the requisites for building a house, and furnishing it, the same being of a soiled and ancient fashion, are also in this museum; there is no catalogue of the articles, but Isaac is himself always on the spot to explain their properties and worth. Two or three dogs guard the exhibition, while he paces about with his cap and barnacles on, to re-adjust this, that, and the other, in some new position; or while he sits within amidst the solitary obscuration of his dwelling, revolving the infinite variety of his possessions; and perhaps then with a placid feeling of thankfulness turning to peruse Baxter's Saints Rest. For Isaac is a great divine, and can reason high on "fixed fate and free will" equal to a bishop, than whom he is far more contented and happy.

From here, we obtain a vista of the Parramatta-road, and the large distillery premises of Mr. R. Cooper, cost it is said twenty thousand pounds. Also the turnpike house, a neat Gothic structure; the Asylum, where the old and infirm, (poverty is non-descript here) find a home; the Carters Barracks, where the juvenile delinquents of Britain, are trained to be workmen instead of robbers; and the new burial ground, which is already half filled up; for people die here it would seem, as fast and as soon, as they do in the raw foggy climate of England. The sight of this cemetery where such numbers are laid, stricken before the term of threescore and ten, has prompted many an exile to turn his steps homeward, or to wander still to some other clime. A foreign grave-yard like this, where no one knows who his neighbour is, for there are no epitaphs here but of good people gone to heaven, can have but little to recommend itself to the imagination. In the flat beneath is the new cattle market, which, from the extent of its accommodation, will need no enlargement for a few centuries to come. The horn sounds of the Royal Mail Coach for Parramatta, to which place two coaches run daily; besides another, at intervals, to Windsor, and one to Liverpool. Full of passengers as usual, inside and outside; fare 5s. and 3s. On the pannels is a well painted Kangaroo, a figure, we take it, which will be stamped on the coin of this future kingdom, unless the image and superscription of Caesar should predominate. What would it be worth to see before us a few centuries? Our eyes ici bas are dim and feeble, but when we look without, immaterially, what fine prospects then! [328]

Sydney is built on a promontory a mile and a half long, being now on the west side covered with straggling cottages, some with neat verandahs and some mere hovels; several of the streets are rocky and impassable, while over the bay which has a few schooners, a brig, and a ship, we see barren craggy shores, islands, and ridges, with stunted trees on them - the east side fronting Port Jackson is at present the most courtly - to this quarter we therefore pass, on to the Race-course or Hyde Park as it is called, an area of half a mile by a quarter, without a tree upon it, and as much like Hyde Park as a river in this country is like the Ganges, the Plata, the Po, or the Mississippi. Notwithstanding, there is a pretty view from it, and a pleasant freshness in the air. We see on the right, rising out of the bush, several neat stone windmills, and the new gaol wall, which is twenty feet high, and four hundred feet square, or thereabouts. Close to where we stand is the mouth of the aqueduct that is to bring water from the swamps of Botany Bay, to supply Sydney, the accomplishment of which, will confer deserved renown, on those by whom it is effected.

Eastward of this park without trees, is the Catholic Chapel, and a view of Port Jackson with its numerous bays and woody shores. This gothic edifice, though a plain structure without the usual architraves, fretwork, moulding and sculpture, is a surprising piece of work, standing where it does. We see in some of the lonely parts of England and near modern vulgar towns, some matchless Gothic buildings remaining, but passing by them, we know that there were giants on the earth formerly! Here there is no such tradition; this fabric has arisen however as a memento of the old world which may excite in the new, reflection, emulation, and general improvement. When the settler beyond the Blue Mountains, the ridge of which we can discern from here, brings his grown-up boy to Sydney to see a ship, he also comes with him to look at the Catholic Chapel, and the conversation which ensues, conveys instruction to one and pleasure to both. This building, begun in 1820, and now roofing in, is in the form of a cross, having at each corner octagonal buttresses rising above the roof with high-pointed caps, ornamented with turrets. These, and a circular projection in the transept for the altar, constitute the principal decorations, yet the whole has a fine effect; and by moonlight, but that the stone is fresh, you might fancy it to be some old abbey, and begin to dream accordingly.

In the valley beneath on the other side is a large verandah cottage with dormer windows, and a row of Norfolk Island pines, each exactly tapering as if cut to resemble a pyramid; and in front, is the little bay called by the lacks Woolamoola. The aboriginal language is certainly beautiful and highly expressive, much more so, we conceive, than any European tongue. Where did they get it? - Gogaga [329] is their name of the bird we call the Laughing Jackass, and Gogaga repeated quick is part of the chuckling notes which distinguish that ludicrous forester. Here we have several public buildings close at hand. The Prisoners' Barracks, called by courtesy Hyde Park Barracks, a neat brick building, in which are lodged and fed five or six hundred men, and in Macquarie's time double that number. Opposite to it is St. James s Church, the Court-house, and a Public School, all brick edifices, capacious, lofty, and well fitted up. There is also the Methodist Chapel, a more plebeian structure than the rest. Churches and chapels are works of imagination, most decided indications. A sectarian considers the gilding his prayer-book would be a waste of money, and that a place of worship built beyond what convenience and shelter from the inclemency of the weather require, instead of feeding the poor, feed vanity and pride. As the sectarian advances in wealth by adhering to these careful maxims, he enters the patrician order and talks of temples to the honor of God; but if not so, if he still follow the lowly path of his ancestors, he is apt to become more degenerate, and then, according to Beaumont or rather Fletcher, the illustrious dramatist, "His only words of health, and names of sickness, finding no true disease in man but money" - he talks much, but chiefly against the shadow of himself.

The Church of St. James's, which is the Court church, has recently been beautified with an excellent organ, which cost £500; and if the south portico of the Church, which is blocked up to make a vestry, were opened, all would then be done that is required to complete the original edifice. The spire of it is framed of wood and cased with copper, lofty and upright, or with but a slight inclination. We will ascend however and see what prospect it commands. The bells here, though the best in the parish, are Lilliputian for a treble Bob major, or for any symphony of a minor cast.

From this height we have a magnificent panorama. All Sydney together is but a little spot, intersected by a parcel of formal streets, with boxes on each side, and here and there a few shrubs. There has been a great pother to raise up the diminutive works we see, some of which appear mighty large and fine, to the mortals beneath. Port Jackson appears like Windermere, an extensive lake, the shores somewhat sombre. The cliffs at its entrance, or the Heads as we call them, are abrupt; on one is the Light-house, a pretty object from Sydney, and behind we can see from this height a narrow portion of the blue main, which seems hushed and motionless, though we can sometimes hear it roar at night when the wind is southerly. Looking over Hyde Park and some green swamps, we see a broad sheet of shallow water with low hills behind it, called Botany Bay, the cognomen of this unfortunate land. [330]

![Explanation of a view of Sydney, exhibiting in the Panorama, Leicester Square [1828/29]](imageslocal/1828-earle-view-of-sydney-burford.jpg)

Explanation of a view of Sydney, exhibiting in the Panorama, Leicester Square ([London: Printed by J. and C. Adlard, 1829]); from original drawings by Augustus Earle

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135783763 (DIGITISED)

One or two cottages on each side, are all that rescue its sandy shores from the dead gloom spread over it by the hand of nature. In a glen nearer, we catch a glimpse of several stone buildings three or four stories high close together, the distillery premises of Mr. James Underwood, who assures us that he has laid out on them one and twenty thousand pounds, without being able to distil any thing hitherto, from the continued high price of grain. The two forts on the edge of Sydney Cove, though not very formidable, add grace and stability to the town, as do also the Government Stables, which surprise the stranger's eye in sailing up the harbour. But the panorama of Mr. Earle is now in London, and in that, our English friends will see all these objects exhibited most faithfully.

It is now evening, and numerous carriages of every description are flying across Hyde Park on to the South-head road. We must descend, and taste a portion of the terrestrial solace which an inn affords. The Rose and Crown, by A. Hill. Mr. H. is the printer of this work; also the Sydney Monitor, an opposition newspaper, published weekly; and two other journals, one by a literate clergyman, the other by a native of the colony, each of which is, or was, published quarterly.

After all there is comfort to be found in the vicinity of Botany Bay. With a breast of veal or a couple of short-legged fowls, a ham and a glass of Madeira, our existence may be rendered tolerable easy even at the very ends of the earth. Pilgrims and wanderers as we have been, a tavern has been to us, for many years, our most common home; where indeed hospitality is not a name, nor the horn of plenty a fable. Sitting in this arm chair with every thing at command for a single word, our thoughts are divested of all care, or envy, or strife, and we hear with equanimity, the happy confusion of talking and singing, now issuing from the Tap and the Dolphin. Let us listen for a moment.

The song, Britannia's sons at sea, words by Thomas Knight, music by William Reeve, in The turnpike gate, a comic opera . . . composed by Mazzinghi & Reeve (London: Goulding, Phipps, & D'Almaine, [1799])

https://archive.org/details/turnpikegatecomi00mazz/page/n17/mode/2up (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: William Reeve (music); Thomas Knight (words)

Britannia's sons at sea,

In battle always brave,

Strike to no power d'ye see,

That ever plough'd the wave.

Fal lal da ral derido.

But when we are not afloat,

'Tis quite another thing,

We strike to petticoat,

Get merry, dance, and sing

Fal lal, &c.

With Nancy deep in love,

I once to sea did go,

Returned she * * *

* * [331]

So now I take my glass,

Drink England and my king,

Content with my old lass,

Get merry, dance, and sing

Fal lal, &c.

This is rather a vulgar song, but we must give Jack his credit, he scorns to be thought a gentleman; besides, he has helped us in many an extremity, sure our "nautical existence began - What is that in the Dolphin?

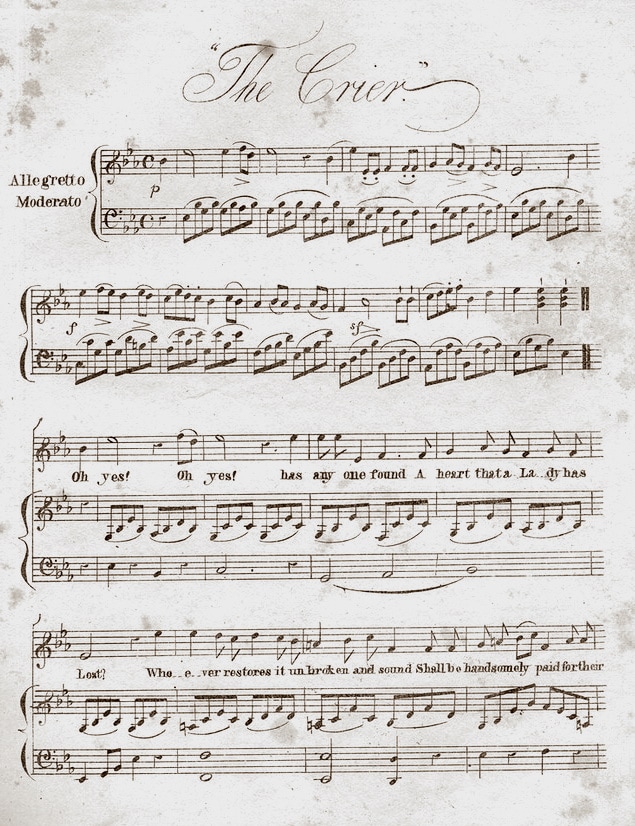

The crier; or, The lost heart, a ballad; written by W. H. Bellamy, esqr., the music composed by C. E. Horn, and sung by Miss Kelly (New York: E. S. Mesier, [c. 1828])

https://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/046/075 (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: William Henry Bellamy (words); Charles Edward Horn (music); the song was relatively new; "as sung by Miss Paton" (Mary Ann Paton) was only first published in London by Cramer in August 1827

Oh yes! Oh yes! has any one found a heart that a lady has lost?

Whoever restores it unbroken and sound, shall be handsomely paid for his cost.

Oh yes shall he, &c.

When first it was miss'd, she cant tell in the least,

But she's reason to think it was stolen;

Oh yes, &c.

Oh yes she thinks that the thief is a youth, who slyly attention had shown her;

Whoever it is, may as well the truth, for it's only of use to the owner.

Oh yes, &c.

What is there in language? men are the same every where - We had intended to portray several strange characters in Sydney, quite unique, but for the present our day's work is done.

References:

The editor of (and major contributor to) The South Asian register reportedly went by the pseudonym of Roger Oldfield; see [News], The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (26 May 1828), 2

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2190451

. . . We have the South Asian Register, conducted under the ficticious name of Roger Oldfield. This Periodical bespeaks talent, research, and labour on the part of the Editor, and is highly praiseworthy for the neatness of its typography . . .

It has been reasonably supposed that this might, correctly, have been Ralph Mansfield, though no hard evidence supports this, and some circumstantial evidence weighs against it.

The Register was printed by Arthur Hill, who was also licensee of The Rose and Crown, and earlier had performed as a comic vocalist in the Sydney Amateur Concerts.

The "Music Warehouse" in Lower George-street had been, until July of 1828, the premises of John Edwards, who was reportedly then "on the eve of settling on his Farm"; Edwards had also been associated with the Sydney Amateur Concerts of 1826

The party of Indigenous people following the military band was headed by Bungaree, a north shore elder.

The military band referred to was one of two active in Sydney in the second half of 1828, the Band of the 39th Regiment, under its master Francis Gee, and the Band of the 57th Regiment, under George Sippe.

The former convict, Billy Blue, popularly identified as "The old commodore" as in the song of the same name; for music (by William Reeve, for The glorious first of June) and words, see, The old commodore, a favorite song, in The glorious first of June, composed by Mr. Reeve ([USA: ?, c. 1800])

https://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/115/070 (DIGITISED)

The verse quoted in the text, however, is the incipit of a different song, With helmet on his brow, usually sung to the tune "Le Pette de Tambour" [Le petit tambour], also sung as The grand old duke of York:

Musical scenes in Sketches by Boz (Charles Dickens and George Cruikshank, 1833-39)

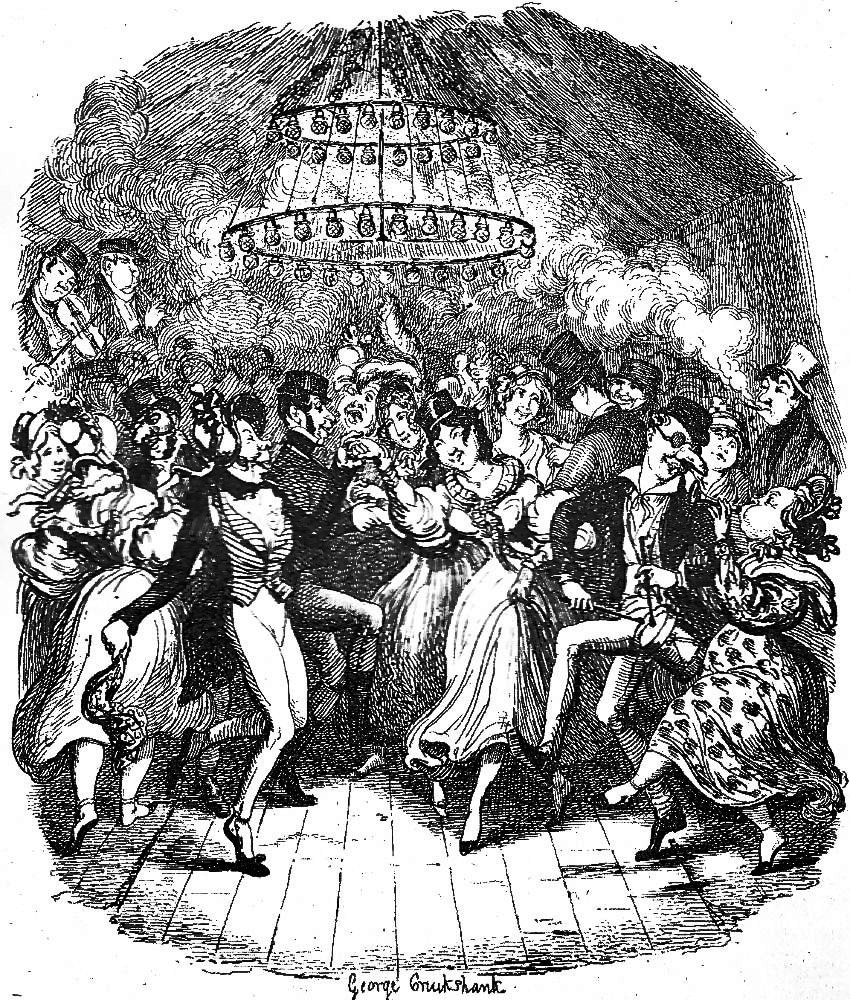

Greenwich Fair (above), by George Cruikshank, etching on copper, 8 February 1836; illustration for "Scenes, chapter 12, in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz (originally published 16 April 1835); Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian web

https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/boz12.html

The grandest and most numerously-frequented booth in the whole fair, however, is "the Crown and Anchor" - a temporary ball-room - we forget how many hundred feet long, the price of admission to which is one shilling. Immediately on your right hand as you enter, after paying your money, is a refreshment place, at which cold beef, roast and boiled, French rolls, stout, wine, tongue, ham, even fowls, if we recollect right, are displayed in tempting array. There is a raised orchestra, and the place is boarded all the way down, in patches, just wide enough for a country dance.

There is no master of the ceremonies in this artificial Eden - all is primitive, unreserved, and unstudied. The dust is blinding, the heat insupportable, the company somewhat noisy, and in the highest spirits possible: the ladies, in the height of their innocent animation, dancing in the gentlemen's hats, and the gentlemen promenading "the gay and festive scene" in the ladies' bonnets, or with the more expensive ornaments of false noses, and low-crowned, tinder-box-looking hats: playing children's drums, and accompanied by ladies on the penny trumpet.

The noise of these various instruments, the orchestra, the shouting, the "scratchers," and the dancing, is perfectly bewildering. The dancing, itself, beggars description-every figure lasts about an hour, and the ladies bounce up and down the middle, with a degree of spirit which is quite indescribable. As to the gentlemen, they stamp their feet against the ground, every time "hands four round" begins, go down the middle and up again, with cigars in their mouths, and silk handkerchiefs in their hands, and whirl their partners round, nothing loth, scrambling and falling, and embracing, and knocking up against the other couples, until they are fairly tired out, and can move no longer. The same scene is repeated again and again (slightly varied by an occasional "row") until a late hour at night: and a great many clerks and'prentices find themselves next morning with aching heads, empty pockets, damaged hats, and a very imperfect recollection of how it was they did not get home.

Sketches by Boz, illustrative of every-day Life, and every-day people (Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1839), 71

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=w2gOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA71 (DIGITISED)

ASSOCIATIONS: Sketches by Boz (serial); by Charles Dickens, illustrated by George Cruikshank

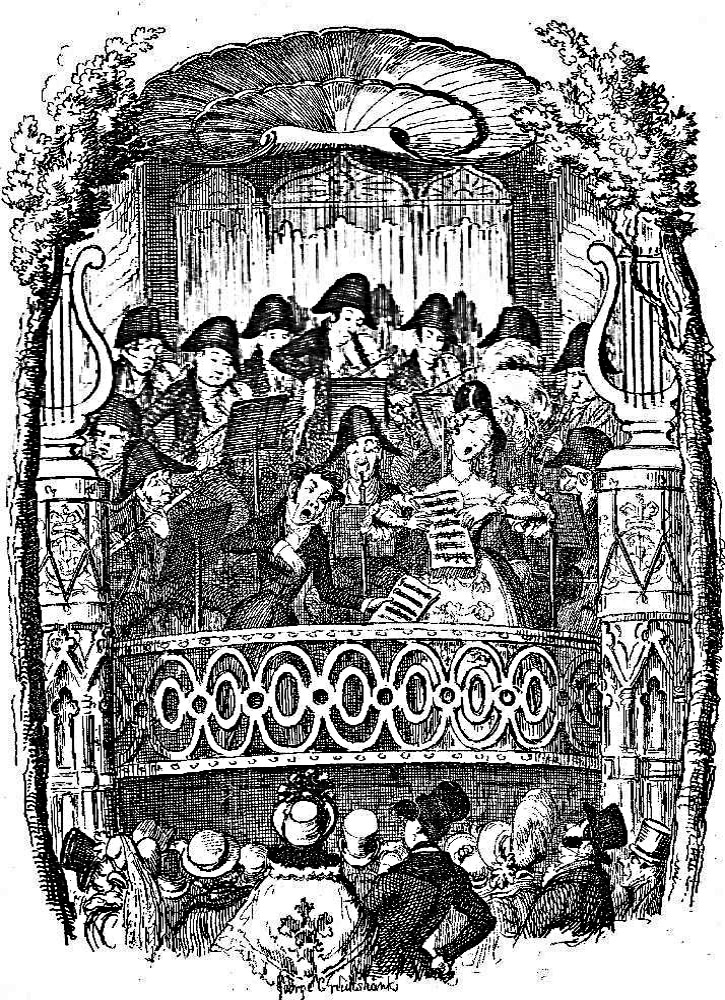

Vauxhall Gardens by day (above), by George Cruikshank, etching on copper, 1839; illustration for "Scenes, chapter 14, in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz; Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian web

https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/boz14.html

. . . but at this moment the bell rung; the people scampered away, pell-mell, to the spot from whence the sound proceeded; and we, from the mere force of habit, found ourself running among the first, as if for very life.

It was for the concert in the orchestra. A small party of dismal men in cocked hats were "executing" the overture to Tancredi, and a numerous assemblage of ladies and gentlemen, with their families, had rushed from their half-emptied stout mugs in the supper boxes, and crowded to the spot. Intense was the low murmur of admiration when a particularly small gentleman, in a dress coat, led on a particularly tall lady in a blue sarcenet pelisse and bonnet of the same, ornamented with large white feathers, and forthwith commenced a plaintive duet.

We knew the small gentleman well; we had seen a lithographed semblance of him, on many a piece of music, with his mouth wide open as if in the act of singing; a wine-glass in his hand; and a table with two decanters and four pine-apples on it in the background. The tall lady, too, we had gazed on, lost in raptures of admiration, many and many a time - how different people do look by daylight, and without punch, to be sure! It was a beautiful duet: first the small gentleman asked a question, and then the tall lady answered it; then the small gentleman and the tall lady sang together most melodiously; then the small gentleman went through a little piece of vehemence by himself, and got very tenor indeed, in the excitement of his feelings, to which the tall lady responded in a similar manner; then the small gentleman had a shake or two, after which the tall lady had the same, and then they both merged imperceptibly into the original air: and the band wound themselves up to a pitch of fury, and the small gentleman handed the tall lady out, and the applause was rapturous.

The comic singer, however, was the especial favourite; we really thought that a gentleman, with his dinner in a pocket-handkerchief, who stood near us, would have fainted with excess of joy. A marvellously facetious gentleman that comic singer is; his distinguishing characteristics are, a wig approaching to the flaxen, and an aged countenance, and he bears the name of one of the English counties, if we recollect right. He sang a very good song about the seven ages, the first half-hour of which afforded the assembly the purest delight; of the rest we can make no report, as we did not stay to hear any more.

Sketches by Boz, illustrative of every-day Life, and every-day people (Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1839), 75

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=w2gOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA75 (DIGITISED)

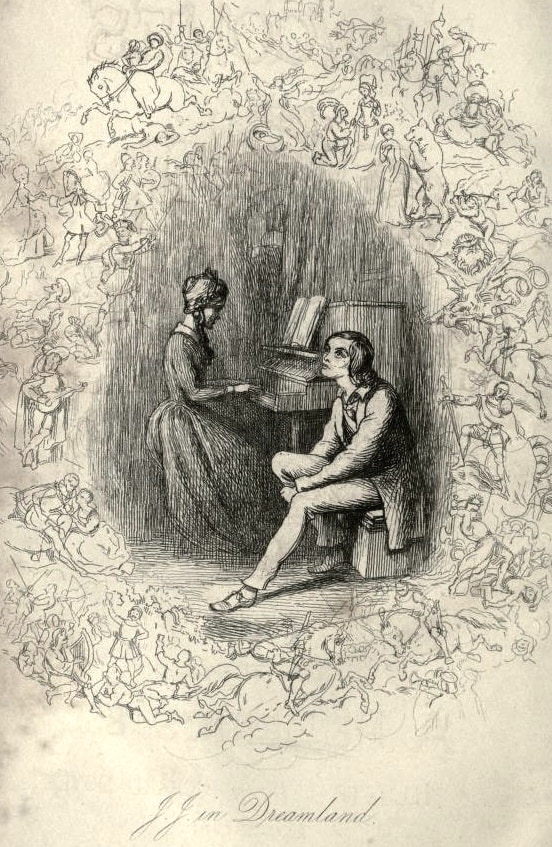

Harmonic meeting in a "cave of harmony" (above), by George Cruikshank, etching on copper, 8 February 1836; illustration for "The Streets - Night", in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz; Paul Schlicke, Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian web

https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/boz42.html

. . . The more musical portion of the play-going community betake themselves to some harmonic meeting. As a matter of curiosity let us follow them thither for a few moments.

In a lofty room of spacious dimensions, are seated some eighty or a hundred guests knocking little pewter measures on the tables, and hammering away, with the handles of their knives, as if they were so many trunk-makers. They are applauding a glee, which has just been executed by the three "professional gentlemen" at the top of the centre table, one of whom is in the chair - the little pompous man with the bald head just emerging from the collar of his green coat. The others are seated on either side of him - the stout man with the small voice, and the thin-faced dark man in black. The little man in the chair is a most amusing personage, - such condescending grandeur, and such a voice!

"Bass!" as the young gentleman near us with the blue stock forcibly remarks to his companion, "bass! I b'lieve you; he can go down lower than any man: so low sometimes that you can’t hear him." And so he does. To hear him growling away, gradually lower and lower down, till he can't get back again, is the most delightful thing in the world, and it is quite impossible to witness unmoved the impressive solemnity with which he pours forth his soul in "My 'art's in the 'ighlands," or "The brave old Hoak." The stout man is also addicted to sentimentality, and warbles "Fly, fly from the world, my Bessy, with me," or some such song, with lady-like sweetness, and in the most seductive tones imaginable.

"Pray give your orders, gen'l'm'n - pray give your orders," - says the pale-faced man with the red head; and demands for "goes" of gin and "goes" of brandy, and pints of stout, and cigars of peculiar mildness, are vociferously made from all parts of the room. The "professional gentlemen" are in the very height of their glory, and bestow condescending nods, or even a word or two of recognition, on the better-known frequenters of the room, in the most bland and patronising manner possible.